Deathloop and the Rise of New Genres

Ideas for a post-roguelike, post-battle royale decade

Deathloop is amazing, let me get this out of the way. Yes, the ending is frustrating and the quest structure has a way of imploding its own premise depending on the path you take, but the journey, friend, the journey is good.

True, Deathloop didn’t create anything from scratch: it is the amalgamation of concepts that had already appeared elsewhere, with a conceptual glue and production values that only a big, well-heeled studio can offer. And sometimes we gotta appreciate that.

In the tradition of Arkane Studios, Deathloop is an immersive sim (or immersive simulator: a game in which every objective can be pursued in many different ways, and where all systems are designed to potentialize the player’s agency and the eruption of emergent situations).

But Deathloop is also the combination of other ideas; ideas that have had captive space in my mind for a while, and is thus the fair reward for the hype I’ve allowed myself to foster.

I’ve written in the past about our natural resistance to discuss development paradigms and to give them names, even if provisory and for the benefit of the conversation — soulslike, botw-like, qwop-like. I’d like to use this space to share some of these “genres” related to Deathloop that I’ve been discussing with colleagues for a while now, and that I think are cool enough for us to try to give names to.

Quick parenthesis here, so we’re all on the same page: I believe there are two ways to look...unintelligent when comparing two products. The first is saying “this is the same as that” (Avatar is just Pocahontas). The other is “this is nothing like that” (Avatar and Pocahontas have nothing in common). No work is born in a vacuum; and no copy is exempt from carrying something its own. Anything in the middle can carry some truth.

Mindvania

You know metroidvanias: there’s an expansive, interconnected world, entirely at your disposal from the start. But the many areas of this world require different abilities to be accessed.

You can only reach that cliff after getting the double jump, you can only cross the volcano after wearing the heat-protected armor, and at the end you need to find the three thingamajigs of power to open the door to the final boss. These abilities are spread throughout the scenery so that you have to come and go countless times, learning and conquering the world as you advance.

A mindvania acts on this same structure, but the power-ups aren’t collectibles that alter the player character — they’re bits of knowledge that alter the player’s own understanding of the game world.

In my personal canon, The Witness is the seminal mindvania, and Outer Wilds is the mindvania by excellence. In both games, the world is all free to explore from the start, but there are “knowledge locks” blocking the way to almost every area. A panel with symbols you can’t read, an invisible entrance, a moon that disappears, a planet taken by lethal storms. By exploring the other sections of the map, in metroidvania fashion, the player discovers fundamental concepts that, by being acknowledged, open the locks and make your head swell.

“But this genre is called puzzle”, you could say, “like that game Myst”. And I admit that it’s been long enough since I last played Myst to think you might be right, my internet friend, and the truth is that these things are not exclusive — this isn’t the same as that, but it also isn’t all different. What distinguishes a mindvania, though, is that:

- Progression is multilinear, with the map distributed in independent areas which are limited only by the collecting of "mental skills”;

- The solution for each puzzle is in an external piece of knowledge that can be found elsewhere in the game world;

- The same mind power-up can be needed several times or open several doors throughout the map, sometimes acting more like an acquired ability than a single-case solution to a puzzle.

A mindvania is less about banging your head on each puzzle until you solve it, and more about exploring the map to find the concept that answers the question. The experience is akin to learning a new language and, bit by bit, grokking the inhospitable world around you.

And Deathloop, ah, Deathloop is a delightful manifestation of the dynamics of a mindvania with an immersive sim and other things, but there it is: if you discover when and how to open a specific door, this knowledge becomes an acquired ability that can be used to taste. Understanding where a weapon or a character lies opens its “lock” and makes future visits simpler. Learning a routine rents a mind space in the portion reserved for the master plan. And all of that is reinforced by that other genre, the…

Loop-like

Game designer Dan Cook has a great piece on loops and arcs, the two structures of interaction we’re used to see in games. Long story short: despite our tendency to compare video games and cinema, movies are based in arcs, while games tend to be all about loops. While the arc starts and finishes, the loop is in everything that evolves based on repetition: our individual and collective rites, our relationships, our learning processes, etc.

The thing is, even though video games have embraced the arc from a point of history onwards, and even though they ended up being great at it, games are particularly good at loops. Specifically when repeating a core mechanic: shoot the targets and get good at target practice, drive your little car and get good at racing, beat your opponents to a pulp and become a renowned street fighter.

But in terms of structure, the loop has always been present in a more clandestine way. We know games in the 80s made you die so you had to buy more credits, from which stems the strong tradition of learning a game by heart so you don’t need to spend money. But even then, beating enemies up is game, while memorizing the level is meta, it’s external — not a part of the core game loop. Even currently, in soulslikes, where players are expected to die several times in order to master the scenery and to be able to progress, this process comes associated to defeat and to regressing in the game state.

Enter loop-likes. In loop-likes, starting again and repeating are actions imbued in the game structure itself, as a requirement to move on. As in Groundhog Day, the events repeat endlessly but in each round we learn a little more.

Even though it doesn’t have time shenanigans as a theme, the seminal example for me is Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, which boasts the most underrated structure of video game history. Explore the level in 3-minute sessions while trying to fulfill all 10 goals in a list; the time limit creates tension, while the repetition creates familiarity and mastery. You can’t die, because “death” is built in the structure itself — starting all over and repeating is not a sign of failure, but an expected step of the game’s contract. After each round, all completed goals stay. Although the time limit may cut the exploration short, all “macro” progress is saved, be it objectives or character improvements.

Other games take advantage of a similar structure, but embracing the time loop as set dressing too. The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask is the oldest I remember, but we’ve recently seen a renaissance, which includes the aforementioned Outer Wilds. Here, the world explodes and restarts each 22 minutes, leaving the player only with any acquired knowledge and a few notes in the ship's board.

Last year alone, at least three games following this paradigm were released: Twelve Minutes, which plays like a point ‘n’ click in a loop; The Forgotten City, which was a Skyrim mod and has you gather clues to solve a mystery in ancient Rome; and our dear Deathloop, which exploded the time loop outwards of the indie sphere, to the point of having trouble communicating its core dynamic to a wider audience. What all of these have in common is:

- The map is the big protagonist, and there are preset moments in which its state gets restarted.

- Restarting the map discards individual gains but also keeps some progress, either material or immaterial.

- Restarting doesn’t symbolize failure and isn’t meta. It’s something infused in the gameplay structure in order to create an experience of familiarity.

Deathloop may be the most loop-lite of the loop-likes so far, for offering constant character growth and for hardly ever closing a loop without any material gain. In that sense, it may even resemble a…

Routine Game

For a while, I have asked myself what would be the mechanic or structure that would allow us to evolve the mainstream out of the cycle of conflict and violence that dominates the games medium.

I think there’s still lots to find, but there is a genre that looks like a light at the end of the tunnel, for the strength of its form and the number of games built on top of it.

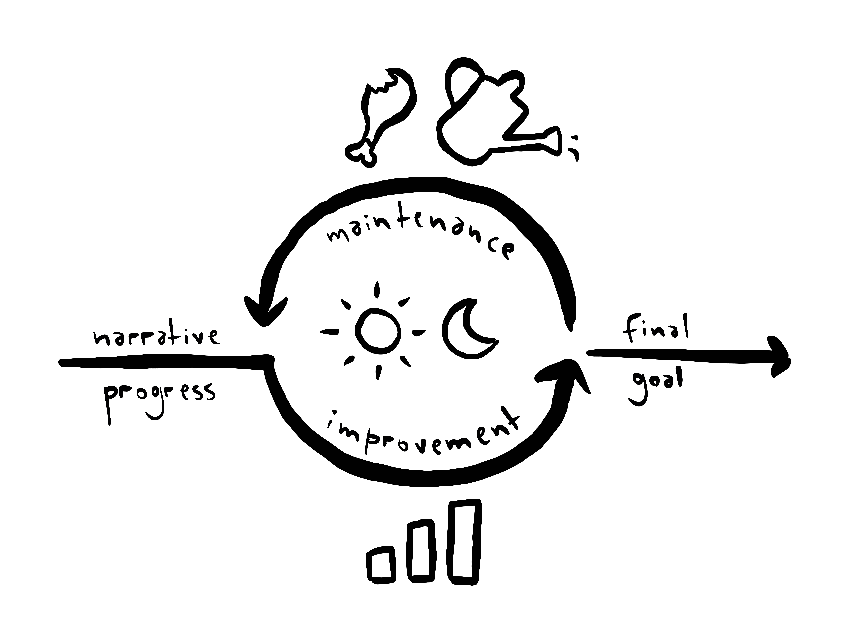

In a routine game, there are:

- A time counter, usually in days, and the player needs to choose how to use the parts of the day (hours, turns, energy, action points) in order to fulfill their goals.

- A cycle of maintenance for things you need to take care of daily (hunger, tending to the farm, school, work).

- A narrative thread that advances as time passes, or as the player reaches certain milestones.

- A progression cycle that ties everything together, making the player become more efficient in maintenance tasks and allowing them to focus on the bigger goals as the game progresses, at the same time as asking them to take care of more varied activities.

The seminal routine games are farming simulators such as Harvest Moon and its younger, better self, Stardew Valley. In Stardew Valley, the maintenance cycle is taking care of the farm in order to get money and invest in things such as supplies, gifts and improvements. The narrative thread is the passing of seasons year after year, with the player getting closer to the many characters of the town and even forming a family. And the progression is making the farm bigger and better, in order to open more axes of maintenance (animals, brewing, mining, etc) and, in exchange, accumulate money quicker.

In Punch Club, maintenance is having to work every day to fund your training; progression is training in your free time to get better at boxing; and the narrative arc is winning the fights in order to discover who killed your father.

In The Escapists, maintenance is the prison routine, with fixed hours to get up, doing the roll call, eating lunch, working, etc, at the risk of being penalized. The main goal and narrative arc is escaping the prison, and progression is the improvements and equipment that viabilize the escape. Here, like in a loop game, learning the scenery is also fundamental to come up with the best escape plan.

In Graveyard Keeper, maintenance is taking care of the dead that arrive at the morgue every week. Progression is evolving the graveyard in order to make this process less slow and laborious, and the narrative arc is getting to know all NPCs to eventually discover why you ended up in the middle ages after being run over in the 21st century.

In Persona 5, a mix of RPG with routine game, maintenance is the obligatory attendance to the classes and dungeons, as well as working to have some money in your account. Progression is improving attributes in afternoons after school and at night, which unlocks new abilities and social interactions. And the narrative arc is the whole thing going on with thieves of hearts and the city at large.

Back to Deathloop: albeit there isn’t a maintenance cycle proper, there is the constant need of collecting Residuum day after day to feed the material progression (infusing weapons, powers and trinkets). There’s also the choice of how to use each section of the day, and a bigger narrative thread that challenges the player to optimize this routine in order to assassinate the big shots in charge of the island. You can’t call Deathloop a routine game as much as you can call it a mindvania and a loop-like, but the similarities are there — not the same, but also not all different.

I see immense potential in these three genres:

- The routine game is a great way to tell stories that aren’t based in conflict — the maintenance cycle replacing the health bar as the dynamic that keeps a level of tension and mechanical engagement.

- The loop-like is excellent to take full advantage of crafted levels, saving in volume while also promoting an experience of mastery, in making sure that the player will explore every nook and cranny of the scenery and get familiar with it, in similar fashion to a speedrunner.

- And the mindvania offers some welcomed structural depth to puzzle games, allowing them to feel a bit less like solving crosswords, and more like detective stories.

I like to think that all of them are gaining traction, and still have a lot to offer in the coming years. Speaking for me, I will always get hyped whenever I discover a new loop-like, mindvania or routine game taking over the headlines instead of the next war shooter.