Graveyard Keeper States the Obvious

Capitalism never stops

Several hours into Graveyard Keeper, my character woke up to find a stranger in his living room. “Come with me to the refugee camp,” the stranger said. “My people need your help.” My heart sank.

Oh god, I thought. Not another one.

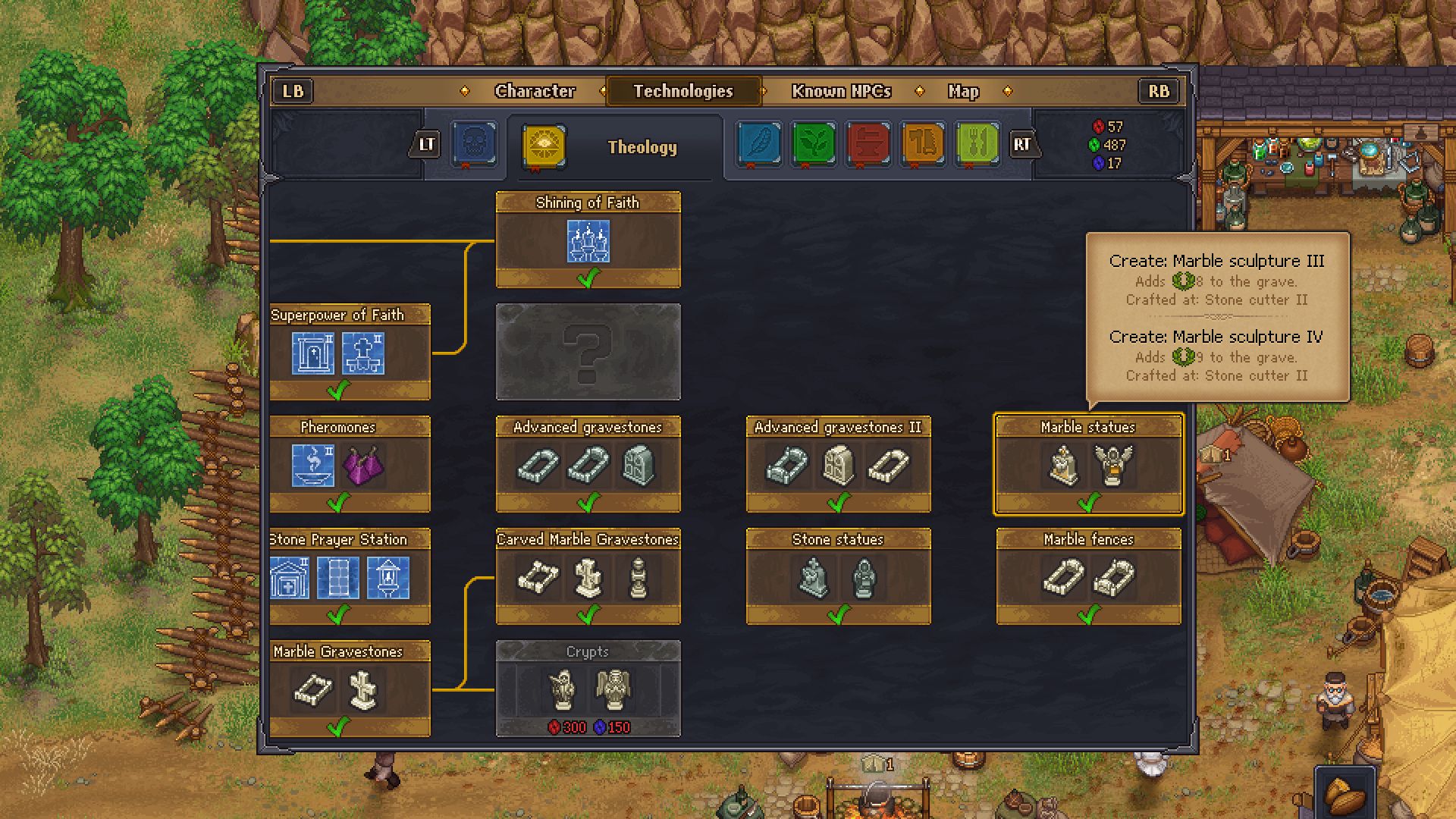

By this point in the game, I had been introduced to a myriad of systems already. There was, of course, the titular graveyard keeping. At the beginning of the game, my character is mysteriously transported into the past and told that he’s responsible for the run-down local cemetery, so I must prep bodies for burial, dig graves, and maintain the overall quality of the graveyard. To keep the cemetery looking nice, I also have to make gravestones and grave fences out of wood and stone, so I acquire axes and pickaxes and mine the land for resources. Doing all this earns me skill points, which I can use to unlock more and better graveyard decorations on the skill tree.

But then the donkey who delivers the bodies to the morgue goes on strike, insisting that I provide him with carrots. So I started farming and unlocking new farming technologies on a separate skill tree, earning a different kind of skill point. Building up the graveyard unlocks the church, so now I preach to the congregation every week, which earns both money and faith points. Faith unlocks new questlines and allows me to study my items, which earns me a third kind of skill point and opens new skill trees. Eventually, I learn alchemy, which lets me revive dead bodies to create zombie workers, but I also have to build up the apiary and help the witch in the swamp and explore the dungeon beneath the church and brew wine and beer and and and and....

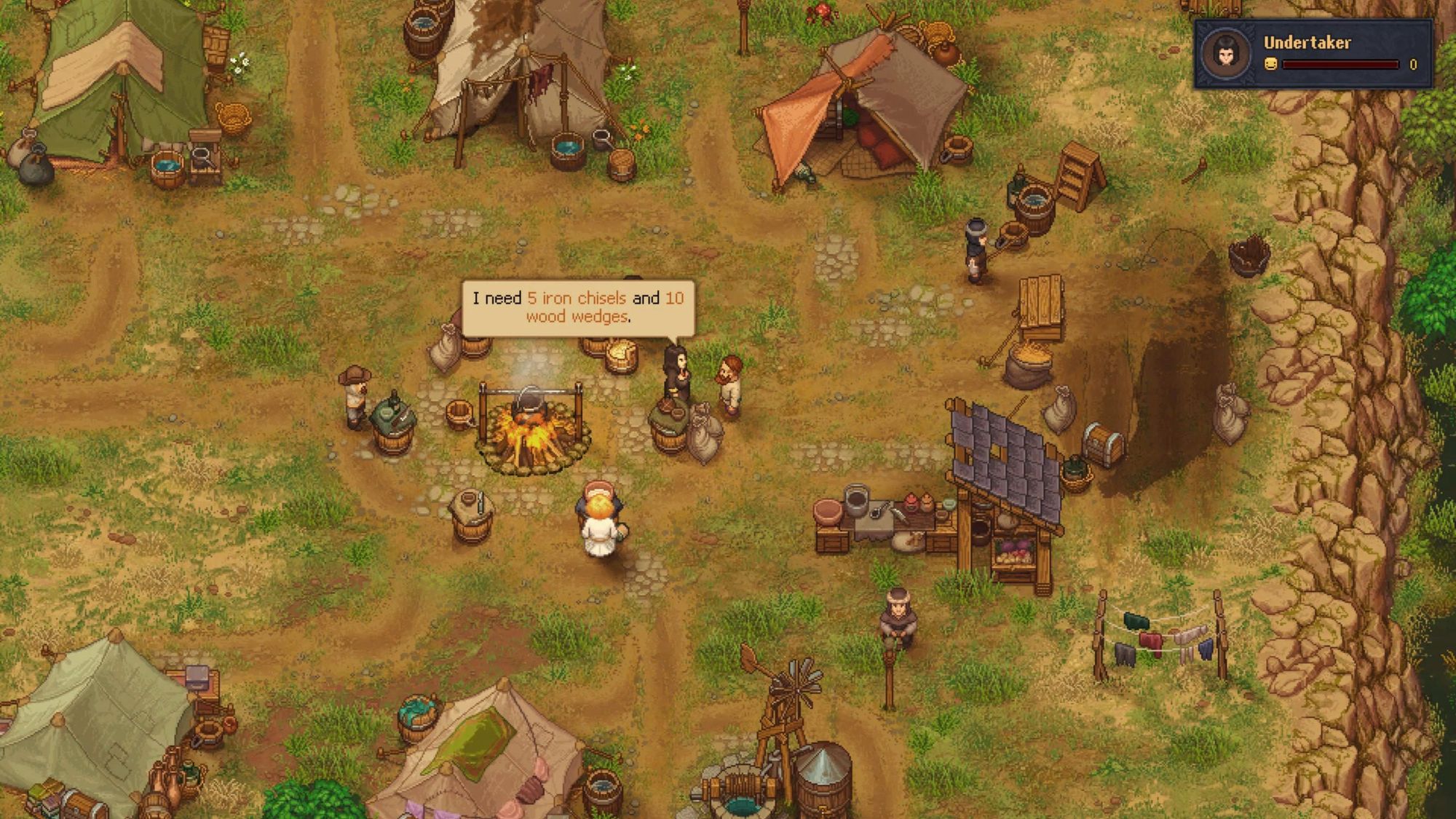

The game is full of stuff. This means when the leader of the refugees showed up in my room, I was more dismayed than excited. Here was another character asking me for something, another questline to follow, another shiny thing to draw my attention. And yet, I followed him, and I started providing food and water to the refugees so that I could build them a well and a new tent. I figured – well, I hoped – that something good would come out of it, eventually. After all, I'd played enough of the game to learn that the end of one quest will click back into a different one, and that all of Graveyard Keeper's sprawling parts interlock.

Not that this structure is unprecedented. Graveyard Keeper is a hybrid of farming and management sim; its cozily autumnal visuals evoke Stardew Valley and Harvest Moon, while the depth and breadth of its systems are reminiscent of place-builders like Parkitect or Cities: Skylines. In these open-ended kinds of games, the reward isn’t narrative, but mechanical. If you do well at one part of the game, your reward is simply unlocking more of the stuff in the game. Beneath the cheery promise of constructing a thriving, happy city or integrating yourself into a cozy rural community, they are basically numbers-going-up simulators.

But Graveyard Keeper is more explicit about it than most because of the way it hybridizes its management and life-sim aspects. Unlike a straight management sim, there are actual NPCs to talk to who all have individual schedules, and the game’s map layout isn’t really customizable; you don’t get the unfiltered creativity of using abstract systems to construct an intricate model of a space. And while a traditional farming or life-sim will go all in on its NPCs, investing a fixed location with a sense of life and purpose, in Graveyard Keeper, NPCs are just funnels for quests. Relationships in this game take on a transactional tone. I give my skull friend Gerry some beer, he gives me lore; I give Miss Charm some faith points, and she gives me another quest. There isn’t any sense of the reciprocity or spontaneity that animates the best Animal Crossing villagers or Harvest Moon spouses.

Instead, Graveyard Keeper replaces these more ephemeral aspects – tone, feel, vibe – with explicit, undisguised grinding. The whole game experience feels designed to slow me down; NPCs all have individual schedules, so I can only make progress on my quests on certain days of the in-game week, but the map is also huge, and getting from place to place takes time. If I don’t make it to the Astrologer before his allotted day rolls over, I have to wait until the next week to advance his quest. This structure invites optimization: when I can find the quickest path from logging to cutting wood to building new structures to preparing bodies to finishing quests, I feel like I’ve accomplished something like I’m beating the game at its own rules. This, I think, is the core of Graveyard Keeper.

The game’s Steam page describes it as a game “about the spirit of capitalism.” When I read that description before starting up the game, I imagined that Graveyard Keeper might offer some sort of commentary or critique of the capitalist drive to acquire mastery over the environment, that its focus on managing the dead space of the cemetery over expanding the living space of the farm might allow it to offer an alternative perspective on the genre. I had hoped and expected to feel connected to the game’s world; instead, the game encouraged me to see its woodsy environs as a daunting challenge to overcome, to neglect my character’s needs to sleep or socialize in favor of endless wood-chopping and stuff-building. In Graveyard Keeper, I am not a person, but a productivity tool.

But isn’t this what capitalism is, at its core? The reduction of our complex humanity, our individual needs and experiences, into the simple outline of a “worker”? In our lives, as we go to work and maintain our ever-more-expensive apartments and watch social media notifications tick in, aren’t we just making numbers go up?

In this sense, I can’t call Graveyard Keeper a failure. It perfectly recreates the endless drudgery and hollow rewards of modern capitalism. It does precisely what it sets out to do. But within the rigorous density of its systems, there’s no opportunity for subversion or meaningful choices; all my time in the game is spent keeping up with its various demands, as that’s the only way to move forward. Graveyard Keeper might be about capitalism, but that's not the same as having something to say. As far as I could tell, Graveyard Keeper’s only statement on the political and economic system that governs our lives is: "Capitalism exists.”