The State of Indie Games in 2025 and Beyond, Part 2

Diving deep into the state of the industry

Welcome back to The State of Indie Games in 2025 and Beyond! In Part 1, we delved into topics ranging from the various genres indie devs are exploring to the ever-growing catalog and subsequent discovery issues of Valve's mega-platform, Steam.

Between the dawn of a new console generation, the delay of some of the industry's biggest titles, and the long-awaited release of others, 2025 has offered small developers a narrow avenue of victory. But how does one achieve that? As the video game industry has expanded and opened up, the keys to success have grown more complex.

There are hundreds of factors determining the games you get to play and whether the people who made them get to reap the rewards. Which genres are the money makers, and which are the dead ends? How do developers navigate a market where a generation's worth of games come out every few months? Who funds smaller games, and what happens when that investment money goes away? How are new tools and technologies changing the game? And what black swans are over the horizon, ready to turn everything upside down?

I've been keeping tabs on this part of the industry for five years. Some of the issues facing these developers are evergreen; others are brand new. All are changing the future of video games.

Click here to jump back to Part 1 to see the full list of the developers I talked with for this year's study. Now on with Part 2!

Opportunities for funding are increasingly scarce

Beyond the eternal issue of Steam's oversaturation, the next biggest problem cited by developers is funding. Years ago, video games - including those by smaller studios - were widely seen as a growth area. Everyone from venture capitalists to some of the world's biggest corporations was pouring money into the market. But with the sector hit with post-pandemic shrinkage and stagnation, the money has gone to safer harbors. For most developers, there's only one significant source of funding left: Publishers.

Not everyone sees third-party publishers as critical. "Publishers as they stand right now are not worth the effort," says Janssen. "They will need to change, or they will be phased out for a big part of the industry. They brought that on themselves, tho."

However, with so few alternatives for securing outside funding, most developers are holding out hope for landing a deal with one of the significant indie publishers. "[P]ublishers are the biggest opportunity to get enough financing and/or visibility," says Emiliano Pastorelli of Hammer & Ravens. "Everything mostly relies a lot on luck, going [viral], or that very 1-in-a-million fantastic and unique and not too expensive game idea."

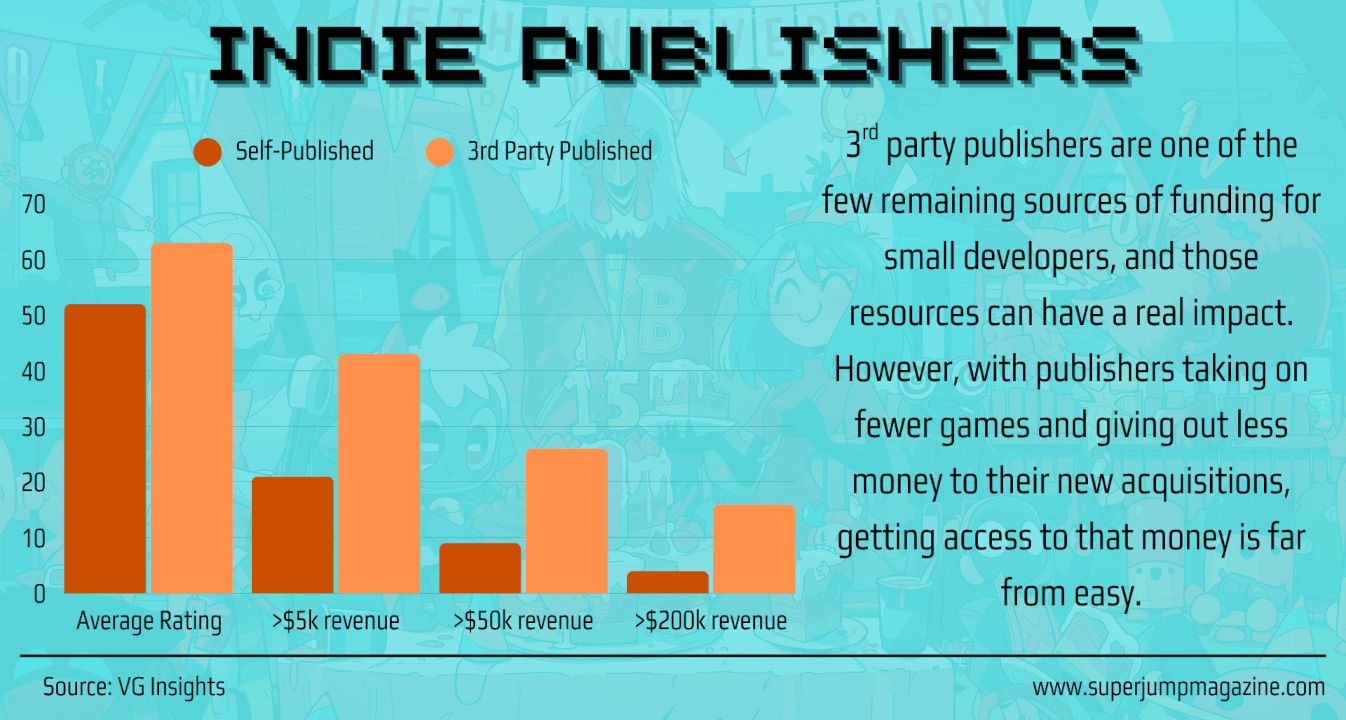

There's no question that games released through publishers do better on average than those that are self-published. An Over Powered Game Marketing analysis of games released in 2024 showed that third-party published games had a mean revenue twice as high and a median revenue five times higher than games without a publisher. Data from VG Insights backs this up, showing that third-party published games are twice as likely to earn at least $5000 and four times more likely to earn at least $200k.

Of course, there remains the causality issue that I identified a few years ago. Do games with publishers overperform because they enjoy increased resources, or do publishers select for games that are likely to overperform? There's no way to rerun the universe to find out which is true. Even so, in a world where a developer must capture a would-be buyer's attention at a glance, publisher resources can offer the professional gloss needed to stand out from their rougher competition.

Developers are getting less money from publishers

The problem is that securing that publishing deal is getting harder all the time. VG Insights shows that the proportion of games on Steam with a publisher has been declining for years. The recent downfall of several high-profile publishers is contributing to this, but the primary issue is how publishers distribute their money. With most publisher revenue coming from a small number of games, it makes more sense to focus on properties that they know will return a profit.

This approach is not a secret. Devolver, one of the larger remaining publishers, released an investor presentation earlier this year that laid out its strategy in clear terms. Moving forward, they plan to focus on DLC and sequels for their more popular games and series while cutting the amount spent on new titles. This isn't speculative, either - Devolver already reduced the average spending per game from $3 million in 2022 to $2 million in 2024, with plans to lower that to $1 million by 2026.

This is a shift that squeezes developers from two directions. The overall erosion of publishers means fewer opportunities, more competition, and longer odds of securing support. Meanwhile, the strategic shifts by these developers mean that the few winners are getting less working capital.

The best news about publishers is that, however useful they may be, they aren't necessary. While non-publishing funding sources are scarce, they do exist in the form of grants and cultural funds offered by some countries. Even for those who can't lay their hands on any capital, the current market offers lots of opportunities to succeed without it.

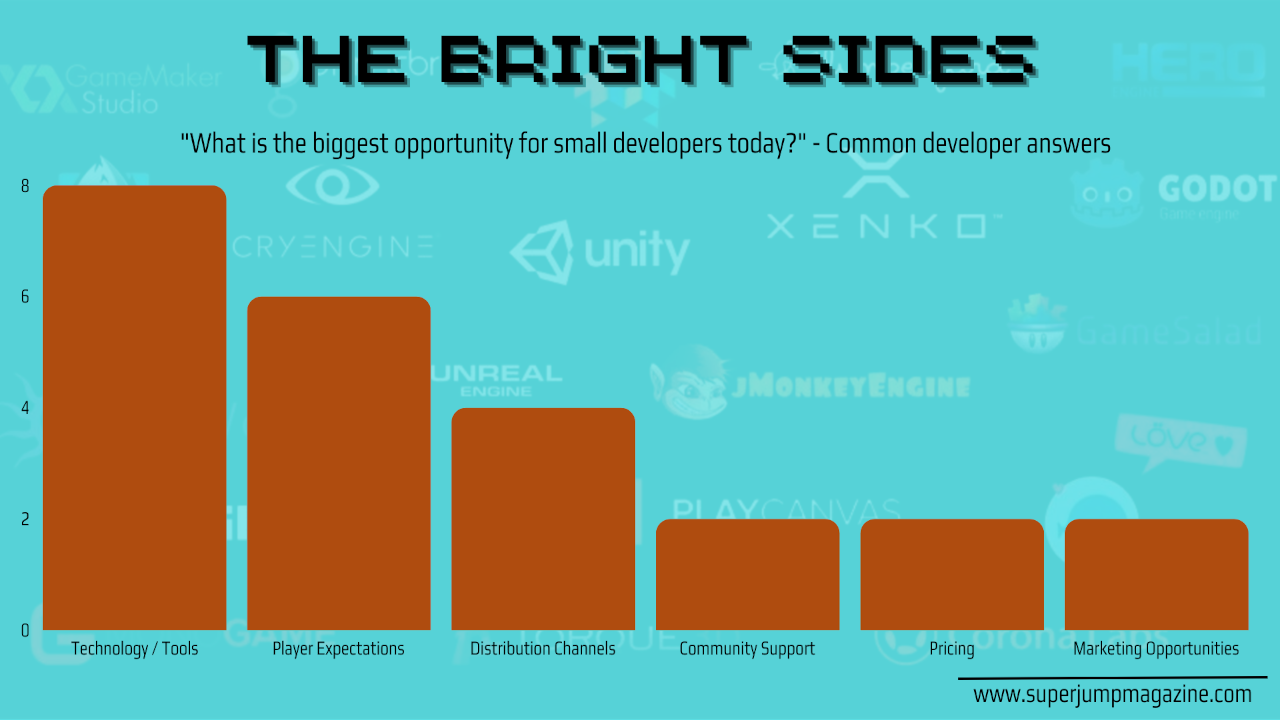

New tools are changing development

"It's never been easier to start making a game, there are tonnes of great tools that are very accessible, and digital distributions are more open than they've ever been," says Dave Lloyd of Powerhoof. "So you can start a business with very little overhead, without needing to depend on a publisher to get your games on shelves, etc. Very different to when I started making games in the early 2000s!"

The biggest opportunities for growing without a budget always lie in the development tools. The off-the-shelf engines that made indie games viable in the first place are still working their magic, and the 2023 Unity scandal hasn't shaken anyone's confidence.

That growth has run both directions, as the expansion of the indie game market has also increased the visibility of off-the-shelf engines, particularly Unity and Unreal. Per VG Insights, more than three-quarters of games released in 2024 used one of these engines, almost double the proportion from a decade before.

"There are so many tools that just didn’t exist 20-30 years ago," says the developer behind Human YoYo. "For example, I find it insane how I can install a free engine that handles physics, graphics, shaders, audio, animation, and so much more."

As with nearly every other field, most of the attention is on so-called AI tools. "The whole AI thing is a game changer," says Roger Gassmann. "It's easier to develop a prototype or find problems in coding. Unlike new tools, which are complex and require specialized know-how and therefore pose a problem for small companies, AI is different."

AI is a broad media term that isn't always useful. It can encompass everything from backend workflow management software to assistance programs for animation and sound to generators for the wholesale creation of assets and code. The latter group has been highly controversial, stoking fears of an unstoppable flood of machine-generated shovelware ready to drown the market at any time.

In reality, adoption of these tools has been broad but limited, and this has changed little in the past 12 months. According to the 2025 Unity Gaming Report, developers are primarily using automated tools for bug testing, enhanced animation, and moderation for online games. These numbers have stayed steady over the past year. There is one category where use of automated tools has declined significantly: Writing. Perhaps due to the backlash over machine-generated assets, there's much less automation in the more creative aspects of development.

Among developers, the outlook here is far more positive than negative. Asked about potential problems and obstacles, Jeroen Janssen says, "...AI is not on this list at all, not even slightly [worried] about games done by AI. There is no soul and no vision there, and there never will be."

Web games are a growing niche

While no one I surveyed mentioned it, we should take a minute to discuss another growing trend: The return of the browser-based game. The no-download online game was killed off with the end of Flash. It was partially revived with HTML5 and .io games, but it's only within the last year or two that they've gained any real footing with a mass audience. Developers are happy to provide, with 15,000 games hitting the web in the first half of 2025 alone.

According to the Unity report, about 11% of developers are considering making a new web game or creating a web-based port of an existing game. That's still a tiny group, but it grows to nearly one-third for the smallest dev teams. These upstarts are more willing to overlook the drawbacks of web games, which are easy to make but difficult to monetize.

At the moment, it's very hard to say how much of an impact these games will have. As a fan of the wild creativity of the old Flash days, I'd like to say that this is a genuine revival. However, the fact that no one mentioned them to me suggests something else. Web games may be of greater interest to mobile developers trying to avoid the overcrowding of their own markets. So while this is an interesting phenomenon that bears watching, it may amount to very little for the kind of developers with whom I work.

Game cloning has gotten much worse

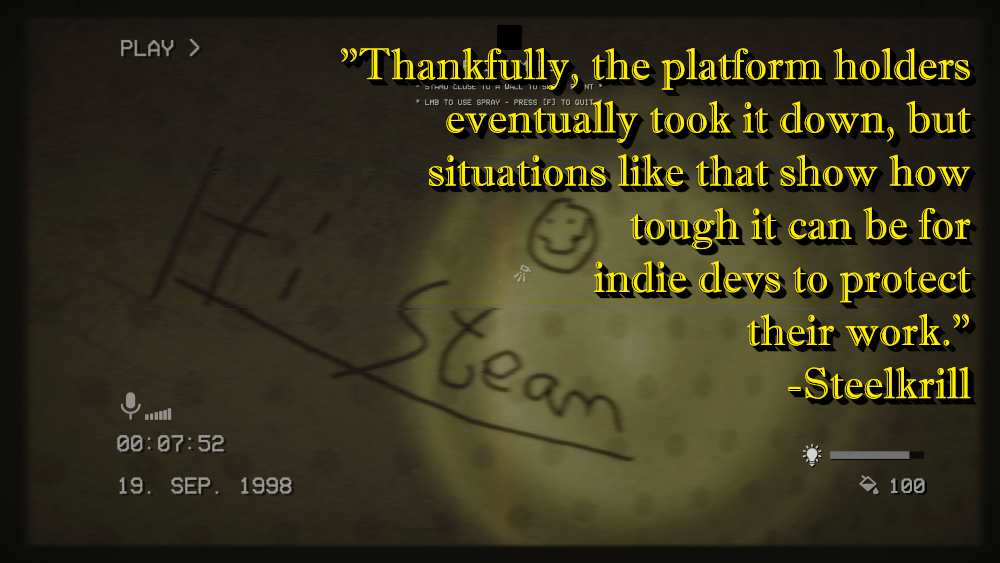

Bad actors are a persistent problem in any field these days, and I don't have to tell you how common scams are. Grifters are targeting everyone involved in games, from consumers to developers, all the way up to storefronts. But there's one particularly crude form of deceit that got a lot of attention this year: The theft and cloning of entire games.

It's a simple grift. The thief purchases a copy of a game, extracts the executable, makes a few superficial changes, and then uploads it onto another platform under a different title. In some cases, the thief may even upload the cloned game back onto the same platform where they bought it, effectively forcing the original developer to compete with themselves.

This isn't a new practice by any means, but it has expanded in an unexpected way. Typically, thieves would transfer games back and forth between Steam and the Android Store, as those markets have notoriously lax standards for entry. This year, we saw cloned games show up on online stores for the consoles, markets that are supposed to be harder to access.

Such was the fate of Steelkrill's The Backrooms 1998, which was cloned by a company widely known for sketchy practices and then dumped onto all three major consoles. The clone was eventually removed from the consoles, but only after a viral Reddit thread and an ensuing pressure campaign.

"[S]ituations like that show how tough it can be for indie devs to protect their work," says Steelkrill. "I still love what I do, but it's definitely getting harder on most parts."

International markets keep growing in importance

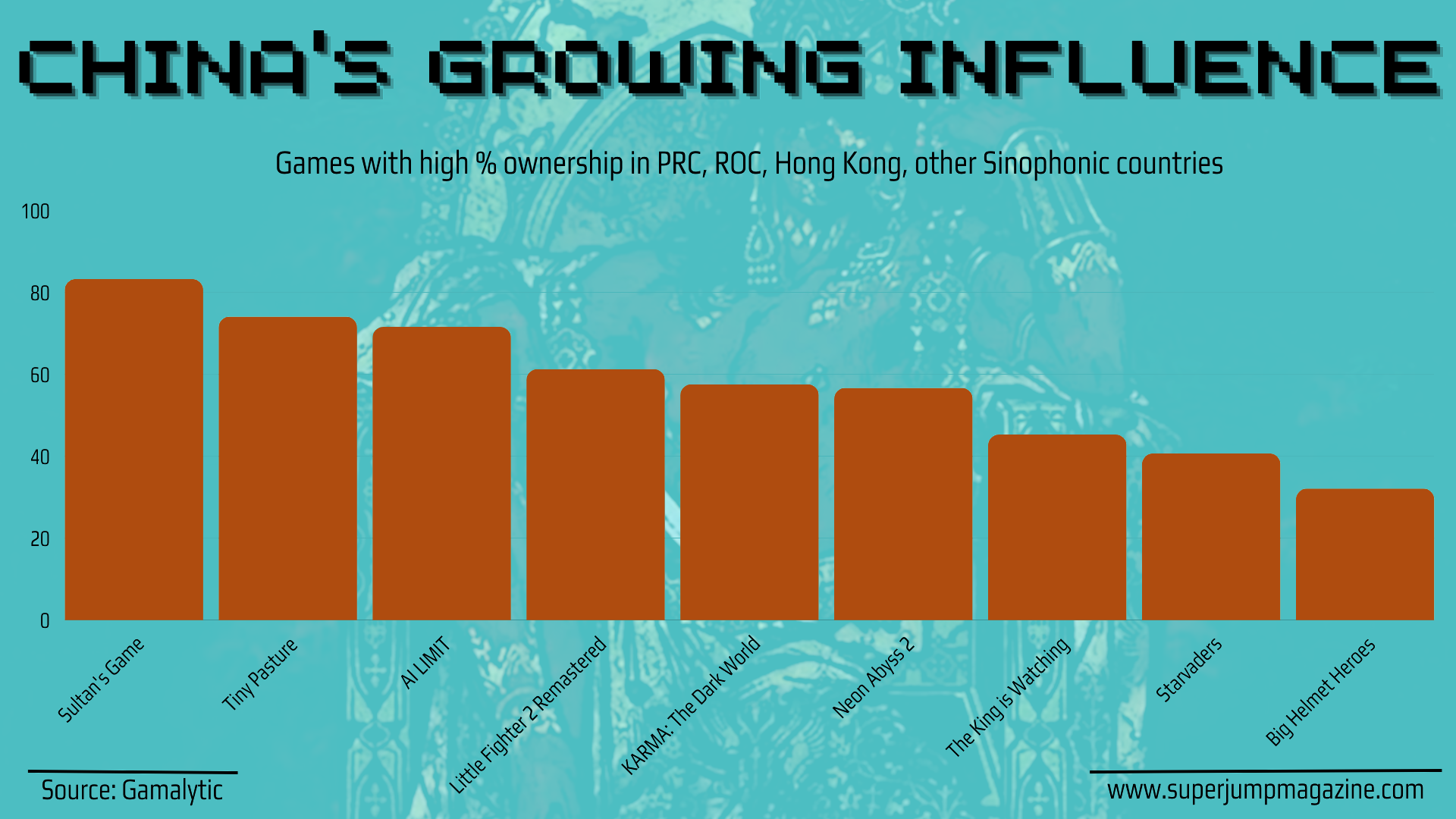

I'd now like to diverge for a moment to talk about Sultan's Game.

The game by Hangzhou-based developer Double Cross is an odd presence on the list of top-selling indies. It's a narrative-heavy game by a developer with little previous presence, one not based on an existing IP or featuring co-op or any other trendy elements. Nevertheless, Gamalytic estimates that it has sold over a million copies, making it competitive with the likes of Deltarune and REMATCH.

Gamalytic also suggests that more than four-fifths of those sales were to people in the People's Republic of China or Hong Kong.

Maybe that's to be expected when a game comes out in such a massive market, but it's also true in smaller countries. Plenty of commentators noted the surprise success of Little Fighter 2 Remastered, a Steam rerelease of a Flash game from the early 2010s. Most of the discussion focused on the growing popularity of these Flash rereleases. Nobody bothered to note that a majority of those sales - as much as 60% - came from the Republic of China, where the game was developed.

Perhaps that's not surprising either, but we can't always chalk this up to national pride. Two Point Studios isn't based in the PRC, but Gamalytic estimates that over a third of all sales of Two Point Museum were in the Chinese mainland. This would mean that there are twice as many Chinese owners as American owners.

It's not a secret that China is important in the video game space, but it's not the only fast-growing market. Poke around and you can find similar results for Brazil, Germany, and the Republic of Korea, among others. This is just a reminder that as the overall market for video games has grown, we've seen a similar trend in indie games.

This is something I harp on every year, but I've often neglected to point out that the development side is every bit as global. The entire industry is becoming more decentralized due to some of the very factors mentioned above. This has resulted in small teams popping up all over the world, as well as international teams. This year alone, I spoke to developers based in, or with members from, Australia, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Italy, Finland, the Philippines, Spain, Switzerland, and Thailand - and I'm sure there are other countries I overlooked.

The world of video games is getting larger, but in this respect, it's shrinking. We no longer live in a world of markets gated off by economics or regulations, but one where everything is available to everyone.

Developer communities are strong in tough times

This global character isn't simply a matter of distribution, either. The global marketplace has given rise to a sprawling network of aspiring and experienced developers. For many people, their ostensible competition is actually a tremendous asset - a valuable source for advice and information.

"The global connectivity of the industry is a major advantage. It has never been easier to learn from others, access powerful tools, and share experiences," says Kipwak Studio founder Guillaume Mezino. "Small developers can now connect, collaborate, and benefit from collective knowledge, which helps speed up development and reduce costly mistakes."

Dave Lloyd echoes the sentiment: "One of my fav things about the industry is how it's always been very open to sharing and teaching others, and there's also so many people making games that you don't have to do it in isolation. So many cities have game-dev meetups so you can hook up with other devs, get inspired, and find help when you need it."

The more time I spend in online developer communities, the more truth I can see here. Without access to the analytical tools and expertise used in the A-tier, small developers instead rely on the behind-the-scenes data of those who've gone before them. The same goes for technical advice, which can range from opinions on the best development platform to detailed information on implementing specific features. And if one person has found a useful tool or an amazing bargain, it doesn't take long until everyone else is in the loop.

Many developers can achieve the same kind of support from the player base. Among my respondents, few had anything too negative to say about the players, and some had already developed healthy communities around their games.

Asked about what it's like dealing with the audience, Vasily Mostovshikov of Mostly Games says, "So far, so good! We have a fanbase, and it did not morph into a toxic dump full of weirdos. Not yet, at least."

That last bit is probably about half joke, half serious. Anyone with a fan base has to wonder if it's going to get disturbing, though this seems mercifully rare. Lloyd says, "95% of players are awesome, it's a very small (unfortunately vocal) minority that aren't awesome people that share the same passion for games that you do."

Comments like these are a reminder that a game - or any similar project - succeeds or fails based on the people who choose to support it.

Developer advice

The developers are not at all in agreement on the state of the market. They are a mix of optimists and pessimists, idealists and realists. Yet even the most cynical among them are not without hope, and there's no one who would outright discourage someone from making a game. It's all a matter of knowing the angles.

Most of them see value in being distinctive and not chasing trends. "The biggest opportunity lies with the unique, but easy to understand game, the concept that attracts masses, or which is unique enough to find its own players," says Vladislav Polgar of Keen Software House.

This isn't solely a practical issue - independence means being able to pursue one's own interests without having them restricted by market forces. "The best thing the indie scene can offer is the opportunity to make exactly the game one wants to, without feeling the need to chase trends or try to copy the formulas of the big hits," says Francisco Gonzales. "Indie games can be as weird or as niche as the developer wants. I think players appreciate uniqueness and fresh ideas."

"I think the biggest opportunity for any developer is to make a game in the genre they love but feel a specific aspect is being underserved," says Adam Kugler. "If you are playing a game and are like - 'this game would be so much better if...' That is the thing to chase."

This line of thought illustrates the single greatest advantage that small developers have over their A-tier overlords. Massive games with massive budgets need to make massive amounts of money. This is what inclines bigger companies toward playing things safe and going with the same boring handful of genres year after year. Upstart developers don't have those same limitations, and that leaves them free to explore new ideas.

In fact, one of the amusing things to come out of this year's surveys was the respondents who thought their biggest advantage was not being AAA companies.

"Biggest opportunity for small teams right now is the fact that AAA and AA sectors are fumbling, and people becoming more aware and willing to consume indie products," says Halil Onur of Team Machiavelli. "With the increased technology in terms of game engines and softwares, you can get something very good with a focused gameplay and the current player base would accept it. If you can go even a little bit bigger, you can even challenge industry giants."

John Szymanski has a similar thought: "Players (specifically the core set of the gaming audience) are currently a lot less impressed with cutting-edge tech and scale and more impressed with games that speak to them more directly. The opportunity to make a low-budget hit (even a small-scale hit) is really high, and won't stay around forever."

The bottom line is that the paths to success are narrow, but they are still there. It's easy to get lost in the shadow cast by bigger titles, but audiences are also bigger than ever, and more varied. There's no telling exactly where the next big breakout will come from.

In the meantime, it's important for developers to stay grounded and remember that money isn't always the goal. "[T]he reward is usually not only financial," says Borja Corvo Santana. "Creating a game is in itself a great personal achievement, and seeing how other people enjoy it, no matter how few, is an even greater satisfaction. So I simply encourage all those who want to try it."

The cracked crystal ball

In lieu of making any predictions for the next year, I'd like to do something a little bit dangerous and look back at some of my old predictions. You are free to scrutinize my 2021 and 2022 predictions and see how many of them failed to come true, either because the market completely changed (remember when every major corporation was trying to build a game streaming platform?) or because I just plain missed the mark (the Steam Deck didn't bring back 2D platformers and I don't think anything ever will).

Here are a few of my favorite bad predictions.

But there was one area where I was correct beyond all expectations. First, in 2021:

Live service-like features will become more and more common in indie games. This will include a greater proportion of titles released in early access, “road maps” with regular scheduled updates and integrated social media features.

And then following up in 2022:

Live service games will hit a saturation point where a combination of excessive competition and rising costs put the style into a slow but steady decline. Despite this, features associated with live service games - what I've called "live service lite" elsewhere - will become increasingly common and will be especially important for profitability in the indie space.

Something interesting happened in 2025. Live service games, which have dominated the industry for a decade, finally reached saturation. It's the fate of any business based on perpetual growth: Eventually, you run out of customers.

Currently, live service games are at a zero-sum point. It's still possible for an individual game to grow, but only by poaching players from the competition. This is probably going to become a negative-sum in a few years as an aging youth demographic drops out of live service games - and perhaps out of video games altogether.

This isn't exactly the "death of live service" that commentators have been prematurely celebrating for the past few years. The biggest games and franchises will still be there and I suspect they'll hang around for a good long while. They just won't be exerting the same gravity on everyone else. Still, the the business model had an impact and the influence will live on, and it will enjoy a particularly robust afterlife in the indie market. As wrong as I may have been about marketing trends or the behavior of big companies, I hit the bullseye on this one. A growing share of games is now devised as ongoing projects rather than one-off releases.

Growing from that, I will make a new prediction: Over the next decade, indie games are going to get bigger. I don't mean that they'll sell bigger, but that the games themselves are going to be a lot more grand and epic.

That's a pretty bold forecast given how much time I've spent talking about how there's no working capital in the market anymore, and the only way to turn a profit is with smaller games. But all of that assumes that a game is a discrete product that's released once. The live service lite model allows a developer to release a complete game, then continue developing it for as long as it takes, using early sales to fund later development. One could spend a decade building a game out, turning something humble into something massive, one piece at a time.

There are still many risks here, and this approach won't work for everyone. Even so, I think that the next gigantic phenomenon game will be released this way. There it is, quietly sitting on Steam with a modest yet positive review total, a humble exterior hiding a fanatical team ready to spend years and years working on it until it becomes the next great obsession.

It might be out already. Maybe you've seen it. Maybe you bought it on sale on a whim and it's sitting in your unplayed section, waiting for you to stumble across it on some dull afternoon.

See you next year.