A Fistful of Coins: The Psychology of Game Pricing

We all have a keen idea of what a video game is worth, but what drives our concept of value?

Let's begin with a thought experiment.

Picture three hypothetical consumers, all of whom are about to purchase the same video game. For this scenario, let's say it's a big-deal release of the early 2000s. Each of the three is going to acquire the game under very different circumstances. Consumer A buys the game within its initial launch window, paying $60 for the privilege. Five years and a console generation later, Consumer B finds the game in a secondhand shop and buys it for $20. Ten years later, Consumer C spots a Steam port of the game on sale for $5 and buys it on impulse.

The question is, did these three people buy the same game?

Objectively, the answer is an unqualified yes. I told you from the start that it was the same game. Subjectively, though, it’s a little trickier. I’d argue that the different circumstances changed their experience of this objectively identical game, from Consumer A - likely a fan of the genre, with views colored by early hype - to Consumer C - a much less invested party with views influenced by a decade and a half of the title’s reputation or lack thereof.

The other factor is the price. That shouldn’t matter, right? It shouldn’t make a difference if you paid $60, $20, or $5, if you rented it from some mom-and-pop for $3, borrowed it from a friend for nothing, or tracked down some ultra-rare limited edition release for $120. The fundamental experience is going to be the same. Subjectively, the circumstances under which one purchased the game matter a lot. Simply put, no one likes to feel ripped off.

This is hardly unique to video games, but what does set the gaming market apart is the precision on display. Reading through reviews, I'm often struck by the number of people who will report exactly how much one should pay for the game. In my hypothetical, Consumer B might not just feel that he paid too much, but that $10 is the amount he should have paid.

Video game enthusiasts have a particular knack for identifying the exact price they will pay for a game. I’m no different here; I do the same thing all the time. Yet what is guiding our instincts when we make these judgment calls? What might that say for the future of the marketplace?

I had no clue, so I decided to run a little survey.

Survey Results & Reflection

61% of the people I talked to shared that they feel video games are too expensive. It’s a common sentiment, and I’m surprised that the number didn’t go higher. Compared to other, similar hobbies and pastimes, video games are certainly on the pricey end. These days, though, there are ways to save money and this may be the key. Video game enthusiasts may think in terms of price because there’s so much variation within the market.

When I was a child, every game had about the same cost, and no one ever talked about a particular title being over or underpriced. Why would they? If every product of a particular type has the same price point, then one doesn’t even notice the price. One can only compare qualities that contrast with each other, after all.

Now, let’s take that market and split it into two tiers - budget and premium - with very different price points. PC gamers have been familiar with the concept of a “budget game” for a long time, and anyone who bought one during the 90s knows you needed to adjust your expectations a bit. A game priced at $20 would not have the same graphical majesty as a $60 game. It’s also likely that a few more bugs have slipped through. That doesn’t mean it’s automatically bad, but you just can’t judge it by the same standards.

The addition of a second price point means that the price is now relevant. A shovelware studio that tried to price one of their games at a full $60 probably wouldn’t have great luck, no matter how good or bad the game might be on its own merits. Even a consumer who enjoyed the game would still view it as overpriced, lacking in the production values and polish that one would expect for the money.

Video games, however, aren’t a product sold at two price points - or three, or four. The range of prices on video games has become expansive and blurry. Setting aside free-to-play titles, a game can run from $1 to $80. That’s before factoring in special editions and all the DLC needed for a “complete” game. Add all that in and the ceiling can easily rise into the range of hundreds of dollars.

Let’s not forget sales. Sales that, themselves, can vary across the fractured video game marketplace. Throw in bundles and subscription services, and the price of a single game can vary dramatically, let alone the price of games.

This is the simplest explanation of our fixation on price. It is a natural feature for fans of any product that has a wide range of price points. That’s only half the story, though. Anyone without unlimited resources will have a limit on what they will pay for a product. What distinguishes video game enthusiasts is the speed and precision with which they identify this limit.

There’s another market where complaints about price are very common: concert tickets. Tickets for live events have an even wider range of price points than video games. Leaving aside free shows, prices for a show can range from a few bucks to hundreds of dollars, even thousands, for perpetually in-demand acts. For all but the cheapest tiers, people agree they cost too much. However, I’ve never encountered that many people who have opinions about specific artists. Most people have a general ceiling - thirty dollars, fifty dollars, whatever it is - and that’s the most they’re willing to pay. Period.

In economic terms, these people have set a level where the utility - in this case, the enjoyment - they get from the concert equals the utility they get from the money, so paying more makes no sense. We can always make exceptions for an artist one particularly loves, or maybe one who doesn’t tour often. It’s easy to justify paying a little more, but overall, that’s the limit. They don’t make this call on a show-by-show basis.

By contrast, I have known people over the years who would show me two games each priced at $40 and tell me they are overpriced but that the first is still pretty good and might be worth buying on sale for $30, whereas the other he wouldn’t touch for more than $20. My survey subjects seemed to agree, as a majority admitted to occasionally passing over an interesting game that seemed overpriced, and to sometimes buying a less interesting game that seemed underpriced.

You can include me in both groups, by the way. There are titles (including some very well-regarded ones) that have been in my Steam wishlist for years simply because, even with discounts of 50% or more, they’ve never reached a price I will pay. As for games that are underpriced, I’ve often reminded myself that some devs will intentionally give a game an unreasonably high price so that they can later throw a 90% discount on it and trick the unwary consumer with the illusion of a great deal. I’m still known to let myself fall for this trick.

Clearly, each of us has the formula to determine the utility of any game, and without the kind of objective metrics one might have for a hardware purchase a lot of this comes down to a gut check. Even so, something is guiding those instincts.

82% of my respondents said that they consider themselves a good judge of how much a game should cost. I’d be inclined to agree here as well. It’s not that I have a fine understanding of the economics of video game development and marketing, but if nothing else, I know what I’m willing to pay for a particular product.

An example: I own a lot of platformers. Over the years, I have played more than my fair share and have a real knack for the genre. I’ll almost never pay more than $20 for one, and even $15 is a little steep. I can’t exactly justify paying more than that for something I’ll be done with in the span of a few hours. I’d be far more comfortable paying the same price for an expansion to something like a strategy title - that’s the smart money.

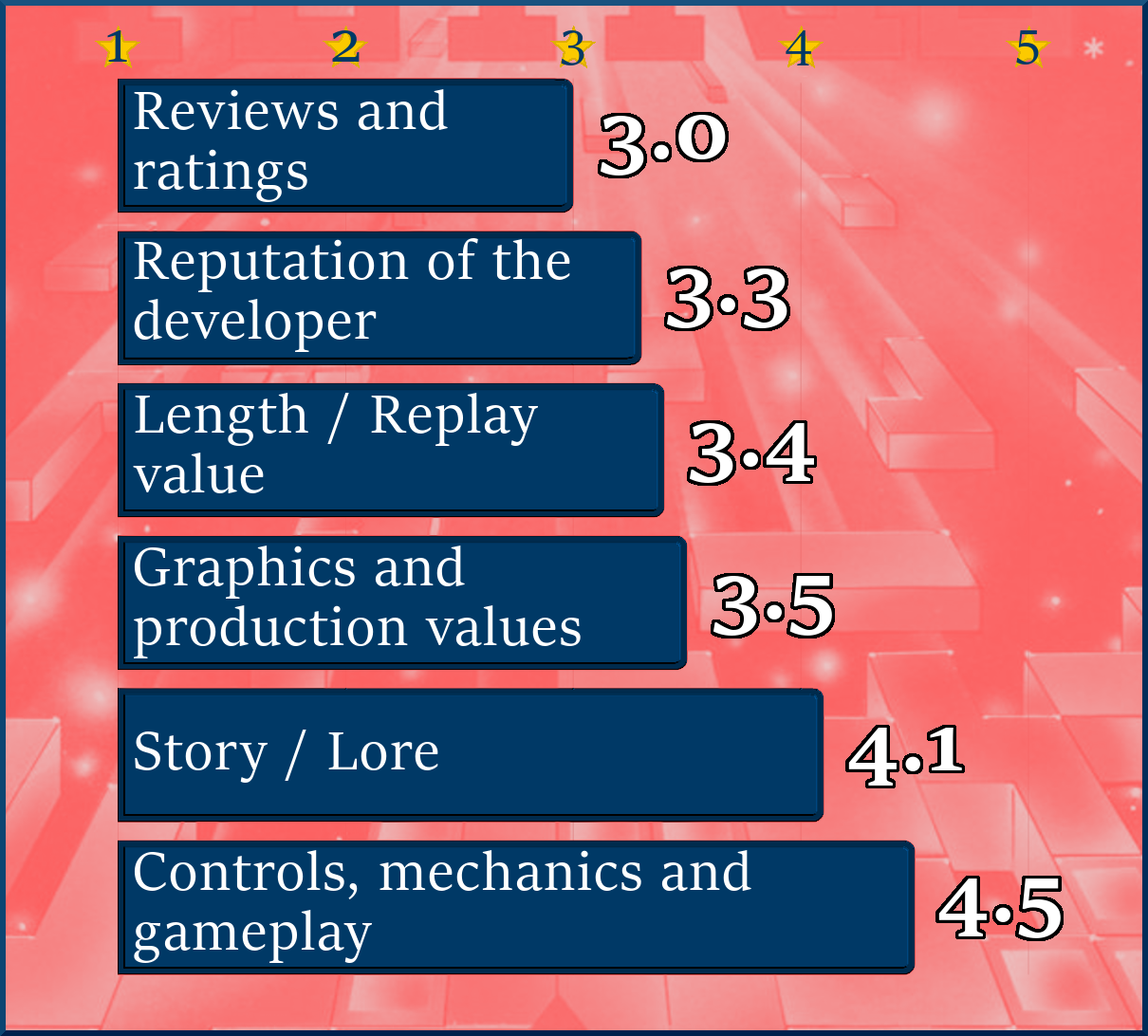

I had a feeling that this would be a common view, but my respondents didn't quite agree.

Maybe the biggest standout for me was the pretty high value put on the story, but maybe that was my mistake. Visual novels are having something of a moment right now, and these are titles that maximize story and minimize gameplay. Then there are the console prestige titles that strive to balance gameplay and narrative, using emotion to move the player as much as the action. These games, which get the lion’s share of the attention, couple the two factors that people told me were most important in valuing a game.

Other Unique Findings

- While PC and console audiences had the same general priorities (mechanics and story at the top, reviews and developer reputation at the bottom), the console audience put more importance on some of them. The biggest differences were in reviews (which the console audience valued at 0.5 points higher) and replay value (0.4 points higher).

- The largest spenders (people who spend over $500 per year on gaming software) put an above-average value on everything but the story, which they put at an average of 0.4 points lower than the overall average. They differed from the lowest spenders (under $200 per year) most significantly in mechanics and developer reputation, both of which the high spenders valued at 0.7 points more.

- People who reported spending an above-average amount of time playing games - 15 hours per week or more put very high importance on mechanics (4.9).

- Finally, people who agreed that video games are too expensive put a much higher value on reviews than those who disagreed (0.7 points). A question on how much time people consider a purchase before making it might be forthcoming in some future survey.

There are some caveats to attach to these findings. I am not a professional statistician and my survey takers were likely heavier players (and spenders) than average for the video game buying audience. The nice thing about heavy users is that they have strong opinions, and some of my survey takers left me with their thoughts.

Several people commented on specific business practices:

I don't think the base price game is too much for a game. I think the industry standard of 60 dollars for a AAA game is fine. What I have a problem with is all the deluxe editions that offer nothing to the player for $100+. I don't like being offered the chance to purchase DLC before I've even played your game, because chances are by the time you release your DLC I will have long since stopped caring about your game entirely and I spent the extra money for no reason.

I will also refuse as a matter of principle to purchase games that I feel are being too greedy in their business model. Eg, if a game has a AAA price AND requires a hefty subscription or heavily pushes microtransactions, it will not get my business at all.

It’s no secret that companies’ attempts to extract extra money from their existing user base turned many people off. Even if these monetization schemes are optional, they simply feel a little dirty - a way to covertly overcharge for a product.

Others mentioned shying away from a purchase for a very different reason: The company may soon be undercharging. The cost-conscious enthusiast almost never needs to full price is he can exercise patience:

If there is a game I am really, really looking forward to (like going to take a day off work to play on release), I'll pay the day 1 price. However, given my backlog, I will wait for a sale. In large part, most games go on discount within a couple months of release.

New release or preorder purchases are personally on the rare side more than ever before. Another big factor is various sales on Steam, PS+, etc. Most games can be bought very cheaply eventually if one can wait for them.

One person mentioned a factor that I opted to leave out:

The presence of multiplayer components for me is a big factor...If a game doesn't have any form of multiplayer then I might still buy it but it does affect my likelihood to buy it. I buy a fair number of mediocre multiplayer games just to play with friends, but I would rarely buy single player games at the same quality.

Of course, multiplayer is a big deal these days, which is probably why multiplayer elements are working their way into a wider range of games.

It's a safe bet that the masters of the industry are keeping close tabs on our spending habits - when we buy, how much we spend, and how we can be nudged this way or that. Companies don't get as large as AAA developers without some insights into their consumers.

From now on, though, it won’t just be the major players with an interest in how the public thinks. Whether it’s indie devs trying to boost sales in an overcrowded market or the marketplaces themselves looking to dominate the competition, everyone has a potential interest here. Look for the rules on pricing to shift a lot more in coming years as outfits big and small invest more time into understanding the market.

In the meantime, I have my tiny little survey. Perhaps I can stumble into some more insights in the future.