Endling - Extinction is Forever

Reducing the world to what matters most

I was raised on the fictional tragedies that define a generation. The Land Before Time, The Fox and the Hound, FernGully: The Last Rainforest, Old Yeller, Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind—these films and their dark stories about humanized animals and environmental struggles created a framework by which I still measure fiction today. Whether it's by my own upbringing, the personal trauma I endured, or the stories that I consumed, I require a bit of sadness and melancholy to really carry a story's impact. A fiction's seriousness, and how well it handles its own artifice, are essential to how it presents its message.

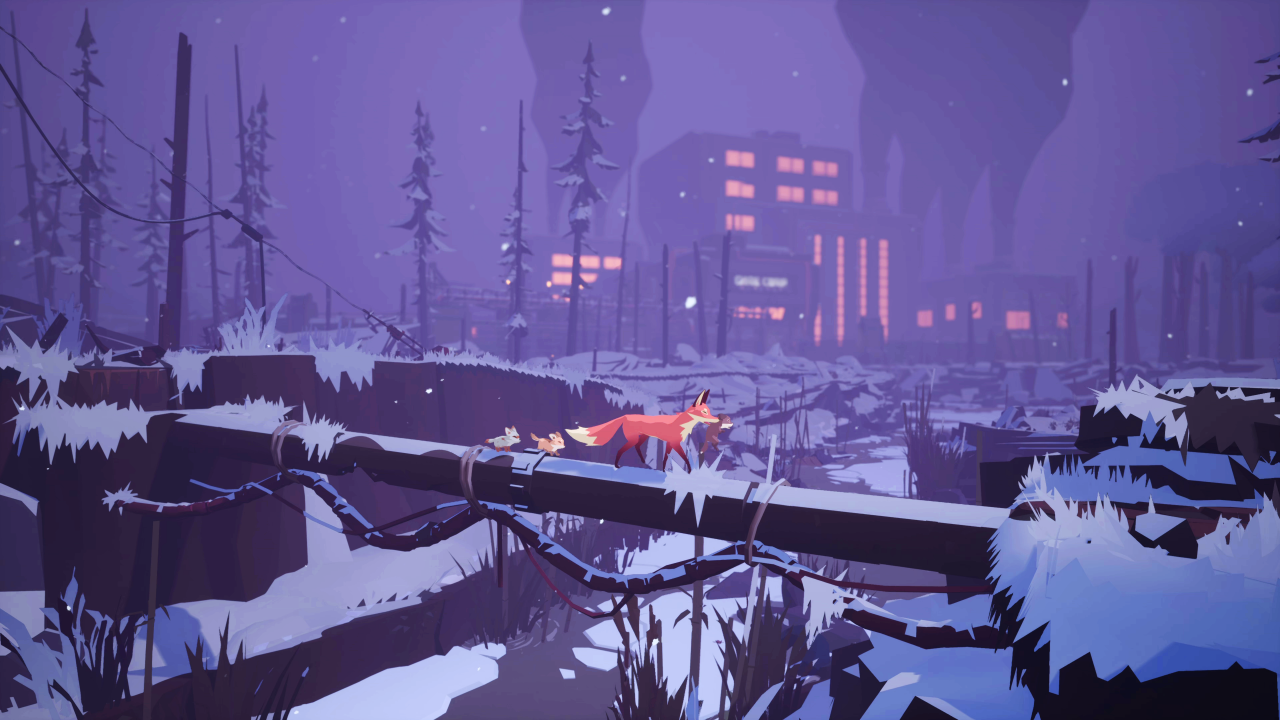

Endling: Extinction is Forever (designed by Spanish studio Herobeat Studios and published by German HandyGames of THQ Nordic) feels singularly driven to impact the player through the specificities of environmental tragedy. Survival is Endling's key aspect, and the game itself feels uniquely stripped of entertainment value in order to create maximum impact with the player.

Life Finds a Way

The story begins in utero, and the camera pulls away to reveal a pregnant vixen desperately making her way through an actively burning forest. As the conflagration spits and crackles around her, this mother fox makes a latch ditch effort to abandon safety in favor of the great unknown that might at least provide a chance for her cubs' survival. After seeking shelter and giving birth, further tragedy ensues—one of her cubs is taken from her by a hunter.

Much of Endling is spent searching for the kidnapped cub while also juggling the survival of the remaining three kits. From the moment the vixen gives birth, the game grants the player a brief stint of cosmetic customization, further endearing the pups' survival to the player. Gameplay is simple, and mostly designed around finding food for the cubs and sniffing out any signs of the missing pup. Food scents are drawn in a green line, and story elements are drawn in a purple line. Events are scattered throughout the map, though only a few are required for the game's actual progression. There are other animals to see, and other people to meet. But the primary intention of Endling is to keep the litter alive for as long as possible.

"We have been developing video games for years, but felt that we were missing the opportunity to deliver a meaningful message and use this medium to reach young audiences that, just like us, are worried about the climate crisis and how next generations will have to deal with the consequences of the present." —Javier Ramello, co-founder of Herobeat Studios

Endling exists in a time of protracted and devastating apocalypse. The game presents this apocalypse by design of industry: factories spew out black smoke, processing plants slaughter animals by the hundreds, and both men and machines fell forest after forest. The mother fox's desperation (and, by extension, the player's) is wreathed in the powerfully silent narrative with its ludic ability to impress the danger in each passing day. Winter quickly gives way to spring, rivers swell and rise, and forests fall beneath the machine of industry. There is no safety in Endling, no comfort, and the mother fox must continue on if there is any hope of survival.

Empathy for the Inhuman

“They killed us with traps. They killed us with poisons. They killed us with snares. They killed us with guns. They killed us with knives. They strangled us. They trampled us. They tore us apart with hounds. They baited steel-jawed traps. They starved us out. They burned us alive. They withheld water. They killed all our prey. They slit our throats. They filled in our burrows. They drowned us. They trampled us under horses’ hooves. They bred us for fur and bludgeoned us to death. They kept us in cages so small with so many we burst apart. They suffocated us with poison gas. They strangled us. They put us in sacks and beat us with clubs. They cut out our tongues so we bled to death. They skinned us alive. They detonated rock and stopped our hearts all unknowing. They swung us by our tails and smashed our skulls against stones. They murdered us in each and every year. They murdered us on each and every day.” —Jeff VanderMeer, Dead Astronauts

In Jeff VanderMeer's novel Dead Astronauts, the sequel to his brutalist nature-punk novel Borne, he grants a unique voice to the voiceless. In an ever-changing world, a semi-sentient fox gathers its friends and promises to save them from the final machinations of a deeply uncaring human world in which their kind is mercilessly slaughtered and destroyed. Dead Astronauts, like many of VanderMeer's novels, grants great empathy to its non-human characters, providing them with a complexity that isn't simply a projection of human emotion. Like so many of the anthropomorphic animal films I watched as a child, this fictional route places an unblinking lens into the voiceless world of creatures that are simply trying to share the same home as us.

Endling paints its humans with little measures of kindness, providing room for optimism between its beats of violence and tragedy. While humans are destroying the world for both animals and man, the game reminds us that "Despite everything, there are still kind people." The humans that remain are mostly climate refugees, with a few workers straggling along in the end times—not to mention opportunistic hunters and furriers that only see opportunity in suffering. Endling's philosophies are not at odds with one another—the game clearly outlines the unsustainability of capitalism and industrialism, showcasing an apocalypse where factories and industries cannot help but farm out the planet's final resources. To ascribe all human beings to the evils of the few is an easy descent into ecofascism; the truth is that corruption must be destroyed at the root, and that none of us will be immune to the social and financial forces that are superheating the planet, destroying the forests, and driving animals to extinction.

The Event of Extinction

"Realism was key because the future in Endling is plausible, not some sci-fi fantasy. Our foxes can't talk to humans or solve complex problems like a human can. We deliberately avoided mechanics that felt too human-like, like naming the cubs. Instead, we relied on scents, sounds, and the soundtrack to convey emotions. Each cub is linked to a specific instrument, and if one dies, that instrument is gone from the music forever. We were super meticulous, making sure every detail contributed to the game's core message." —Javier Ramello Marchioni

It is estimated that today's extinction rate "is hundreds, or even thousands, of times higher than the natural baseline rate" according to the Smithsonian Institute. While extinction events are nothing new to our planet, we are generating not only the extinction of plants and animals but of ourselves. Throughout Endling, the mother fox desperately sifts through garbage, avoids traps, dodges hunters, and moves farther and farther afield, all to provide sustenance for her growing clutch of cubs. With each passing day more and more of the world is lost; one day you wake up in a lush green forest, and the next you wake up in a destitute valley piled with logs and populated with roving machines. Endling does a terrific job of pinpointing the exact confusion and fear that comes with being a surviving animal that cannot comprehend what is happening around them, and how the damage that human industries wage on these species is both physical and psychological.

Within its short runtime, Endling is able to make its point with a heavy hand—there is no happiness to be found here. Although it is possible to reunite the cubs and keep the family alive, eventually the mother fox will run out of places to make a home. Like so many clever and artistic games accomplish these days, Endling is able to transfer profound emotions without a true spoken word. Its eco-consciousness ebbs and flows, but the game sticks its landing with a truly dour point, and when the credits roll, the experience is profound. Endling makes a great case for the value of games beyond entertainment; while I played the game twice back to back, I can't say I had "fun" while doing so. Experiencing Endling is less about any casual enjoyment, and more a sobering reminder about how we exist in relation to all the other animals on this planet. If there lies any hope in Endling's dour ending, it is that within the fenced-off area there might be a portion of the world that is still protected.

Awareness As Art

"From the start, we wanted video games to be more than just fun. We aimed to raise awareness and engage a diverse audience, including young people and those concerned about environmental and social issues." —Javier Ramello Marchioni

This narrative tale is about climate change, survival, cruelty, and hope. It's refreshingly lacking in humanism, instead granting us a perspective that reinforces the importance of life for all living beings regardless of their perceived level of consciousness. Most importantly, Endling is not afraid to inflict pain. The emotions that resonate through Endling are surprisingly cruel, and many players might balk at the game's rather downbeat ending. To me, it's obvious that the developers wanted to generate the same feelings that many eco-conscious films generated back in the 80s and 90s—your personal comfort and good feelings are not as valuable as the point that is being made.

There is no good and bad when in the throes of survival, and much of Endling is left open to interpretation. It's obvious that the developers sought to make an experience about climate change and the violent machine of industry without painting all humans as morally repugnant parasites. It's possible for all living things on earth to live together in harmony, and to survive—we just have to pare away the things that are killing us and focus on what matters.