Footsteps Through the BrAIn: Ludonarrative Memory

Storytelling through an unreliable mind

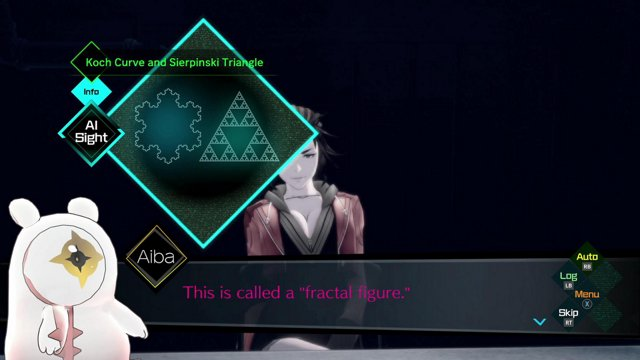

“Human memory is fractal. If you retain even a single piece of it, it’s possible to recreate the whole thing.”

Kotaro Uchikoshi has had my number for over a decade, now — the Zero Escape series is one of the most formative bodies of work for not only my writing, but also my perspectives on life, the universe, and the 7.9 billion people living in it.

Ai: The Somnium Files is Uchikoshi’s latest work, and much like its predecessors, it establishes a potent ludonarrative link with the player. In this case, that link is formed through memory — all knowledge that the player has relating to certain details of a murder investigation is filtered through the main character’s cognitive state. Before finally solving the case entrusted to our charming protagonist Kaname Date, players must progress through the “Annihilation Route”, an extended bad ending scenario (analogous to similarly required bad endings in Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward, another Uchikoshi game). It is here that Date learns the true nature of the information he has pertaining to his case, but should not logically know.

The player is, of course, aware of the things Date mentions: the location and functioning of a body-swapping machine he has never visited nor used, for example. Until this moment in the Annihilation Route, however, neither Date nor the player knew how they came into possession of this information. It is initially posited as a hunch, a flash of intuition. But nothing in a game written by Kotaro Uchikoshi is ever a lucky guess — as it turns out, Date does not own the body his mind currently occupies.

This body belongs to someone else, and that person’s memories still exist between the jagged lines of its brain. “Even after the [machine’s] personality exchange is complete,” one character explains, “the host’s memory isn’t completely lost. About one percent remains in the brain… human memory is fractal. If you retain even a single piece of it, it’s possible to recreate the whole thing. Pieces of memories are like roots that grow into every corner of the brain. Gradually, slowly, taking its time… I imagine the same thing is happening in your brain right now”.

I’m no neuroscientist, but thankfully, I know one — my close friend is a postdoctoral researcher in a neuroscience lab, and also happens to be an Uchikoshi fan. He explained that the game was likely referencing a process called “pattern completion”. When a memory is first created, neurons fire in a specific pattern, leaving an imprint in the brain; think of it like a trail of footprints in the snow. During memory recall, the brain is thought to “retrace its steps”, as if walking back along that same path of neural footprints.

Though Uchikoshi’s use of fractals as an analog for pattern completion is the stuff of science fiction, it creates an ideal in-universe explanation for non-diegetic elements of gameplay. Everything the player knows about the ongoing investigation is filtered through Date’s own process of pattern completion. Date and his adversary’s memories feed on each other, developing alongside the player’s understanding of the story. Like a recovering amnesiac, the story guides us to “remember” a past that doesn’t feel like our own.

Alongside Ai: The Somnium Files, another game contending with the intricacies of the human psyche came out in 2019 — Disco Elysium, a CRPG developed by Estonian indie studio ZA/UM. We play as Harry, a police officer recovering from what seems to be a bout of near-total retrograde amnesia (and alcohol poisoning). Both his semantic and episodic memory suffer to varying degrees, and the player must push on to solve a murder case at their mercy — and at the mercy of a disco-loving, terminally-divorced personality who has all but given up on himself and the world.

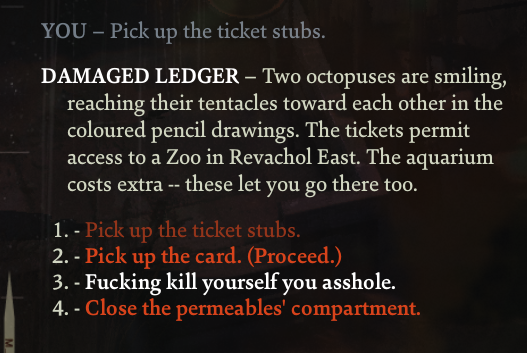

The player’s dialogue choices are a major driving force in the story — you can essentially choose whether to let Harry continue his downward spiral into substance abuse and heartbreak, or to help him regain his footing and sober up in a world he knows precious little about. As with Date, information is granted and withheld from the player in accordance with Harry’s mental state. In particular, Harry’s tendency to half-remember fragments of his own past manifests (for better or worse) in some very visceral, evocative dialogue choices.

Despite its absence, Harry’s memory is one of the most crucial forces in Disco Elysium’s story and gameplay — the information we do not have speaks just as loudly as the lingering resentment and fondness Harry feels for the world around him. His disjointed understanding of reality, along with the unspoken, unknowable gaps in his knowledge, inform our every decision and color every conversation. Characters who knew Harry previously in his life struggle to contend with his new normal, just as we contend with the mess of a man we’re dealt. We chase Harry’s impulses, piecing together for ourselves why he might be so fixated on the scent of apricots, or why he obsesses over fictional boxer Contact Mike. We exist as an extension of Harry’s neuroses, their only witnesses. Just us, the city of Revachol, and the whims of the dice.

Unlike Date, Harry has demonstrably poor luck with pattern completion — rather than retracing a given set of footprints in the blizzard of his liquor-addled mind, he paces wildly in all directions. His attempts to recall key details of his past frequently cause him mental (and sometimes even physical) pain. This failure, too, is a core aspect of the game’s narrative framework: players are encouraged not to reload saves after they miss a dice check or flub a line in conversation. Harry is a man of failure, himself. That he manages to pick himself up and continue anyway is analogous to our own mistakes, and our subsequent laughter, shame, or triumph.

The story of Disco Elysium is, in itself, about memory: about yearning for bygone days, the fallout of a revolution lost, and the cold morning after a night on the town. As Harry copes with a reality that seems to have left him behind, the player learns more about the world of the game and the people living in it. One such person he meets in his travels is a character named Lena, who struggles to recall the details of a cryptid sighting she experienced as a child. She confides in Harry that she worries she was wrong and has set impossible expectations for the people in her life. “I’m not sure of anything”, Lena says. “Sometimes I still see it, you know. The real memory. Not the memory of the memory, but it’s so hard to tell the two apart”.

Between Date and Harry, however, is one core difference related to the design of both games. An Uchikoshi game is very often a tightly-packed puzzle box where failure is not possible. Even the bad endings are deliberately funneled into the true conclusion of the story — his main characters tend to have just the right amount of cerebral organization to emerge victorious from a sunken ship in the middle of the Nevada Desert. In Disco Elysium, however, Harry is a human disaster. His failures are also factored into the game’s design, but never rewarded in quite the same way; his mind is anything but organized, making him an extremely unreliable narrator. There is no such thing as objective fact or true closure for Harrier Du Bois. There is only the present and what he chooses to make of it.

Each time we retrace our neural footsteps in memory recall, we risk losing or mixing up the details of our experiences. We may begin to doubt the authenticity of our own lives. In both Disco Elysium and Ai: The Somnium Files, perhaps the most important things are the feelings that stay behind, even when the memories attached are murky and uncertain. The love Date holds for his found family, Hitomi and Iris, helps him solve a chain of serial killings, even though he could not fully recall the time they spent together. Harry wears his heartbreak like chains, the weight constantly bearing down on him; as much as they hurt, he must confront the echoes of lost love in order to move on and learn from his mistakes. Both games, in linking our own memories with those of their respective protagonists, grant us a window into emotional experiences that only an interactive medium can offer.

Despite gaps and inconsistencies, we find catharsis at the end of memory, and beyond it — we chase the promise of new stories and experiences, of leaving fresh footprints in the snow.