The Quest for Knowledge in The Witness

Deep understanding of a deep game

The Witness is one of the few video games, even within the puzzle genre, that has epistemological questions at the core of its game design, such as "what is knowledge?" "How can we know something?", and "What are the limits of what we can know?" At the same time, this game is also one of the first in its genre to be a 3D open world, and it is the first to attempt to reconcile a complex progression of puzzle mechanics with freedom of exploration in an open world without any tutorial or interaction with NPCs. Our goal in this essay is to show how the gaming experience in The Witness is closely related to logic and epistemology.

First of all, it is important to clarify that The Witness does not offer answers to the epistemological questions. It is the job of philosophers to propose solutions and to precisely formulate theoretical problems, while the role of artists like Jonathan Blow (director, designer, and writer of The Witness) is to reveal issues in an inspiring yet vague way and to show perspectives on how to look at them. In this sense, while its gameplay is enjoyable enough for puzzle fans to enjoy it solely for its puzzles, The Witness is also a remarkable expression of video games as art, and can be appreciated for both aesthetic and conceptual reasons.

This essay is divided into three sections: first, we will address the logic and knowledge of The Witness; second, we will discuss archaeological interpretations during the exploration of the Island; third, we will analyze epistemological commentary in audio logs, videos, and metafictional elements.

Table of Contents

I. Logic and Knowledge

I. i. Knowing-that and knowing-how

I. ii. Formal puzzles, empirical puzzles and logical reasoning

II. Archaeological interpretation

III. Metafiction and intertextuality

I. Logic and Knowledge

I. i. Definition of Knowledge

This section argues that The Witness stages an epistemological experience in which players acquire non-linguistic propositional knowledge through rule discovery, hypothesis testing, and logical abstraction. Before addressing the specific puzzles or audiovisual and narrative strategies of The Witness, it is necessary to clarify what kind of knowledge the game deals with. In classical epistemology (based on Plato's Theaetetus), knowledge (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2017) has often been defined as justified true belief: to know something is

- to believe a proposition (e.g., to believe that "The Witness is a videogame"),

- the proposition being true (by correspondence theory of truth, this means that there exists an object called "The Witness" and that this object is classifiable in the category of what is called a "video game," according to some definition of video game), and

- that belief being supported by some form of justification. For example, it is found that The Witness is classified as a game in an app store. Note that the definition does not require strong empirical justification or a formal demonstration.

Although contested in contemporary philosophy, particularly through Gettier-style counterexamples that question the adequacy of justification in certain supposed knowledge, this classical definition remains a useful conceptual framework as a starting point, as well as for distinguishing knowledge from mere opinion, guesswork, or habit. In this section, our focus will not be on the notion of truth. It is worth mentioning that it is possible to apply other theories of truth besides correspondence theory to interpret the epistemological experience in this game.

At first glance, the player's epistemological experience in The Witness seems far removed from the classic definition of knowledge. The game has no NPCs or dialogue, offers no explicit propositions to be true or false, no textual statements of rules, and not even direct explanations that could be classified as beliefs or justifications. No phrase tells the player "this is how the puzzle works" or "this scenario is a city." However, throughout the experience, the player undeniably acquires knowledge: which lines are allowed, which restrictions matter, which visual elements inside and outside the puzzle space are relevant and which are merely decorative. This apparent paradox forces us to be more precise about the types of knowledge involved.

A useful starting point is the traditional distinction between knowing-that (propositional knowledge) and knowing-how (practical or procedural knowledge). Much of The Witness clearly involves knowing how to solve certain types of puzzles, all inspired by maze puzzles. However, reducing the player's learning to the mere acquisition of skills would be to ignore that the game design compels the player to develop a conscious understanding of the rules.

Solving a panel by mechanically reproducing a pattern is not equivalent to understanding it, and the game is carefully designed to expose this difference: players who rely solely on imitation or trial and error quickly reach a point where they can no longer progress, as more complex problems require the player to have abstracted a general rule from the initial puzzles of an area. Of course, as an open world, the player can choose to abandon that type of puzzle and explore another part of the Island, but they will also face similar obstacles in that other place. What is indirectly required is not just how to solve the problem, but an implicit understanding of why certain actions by the panel are correct.

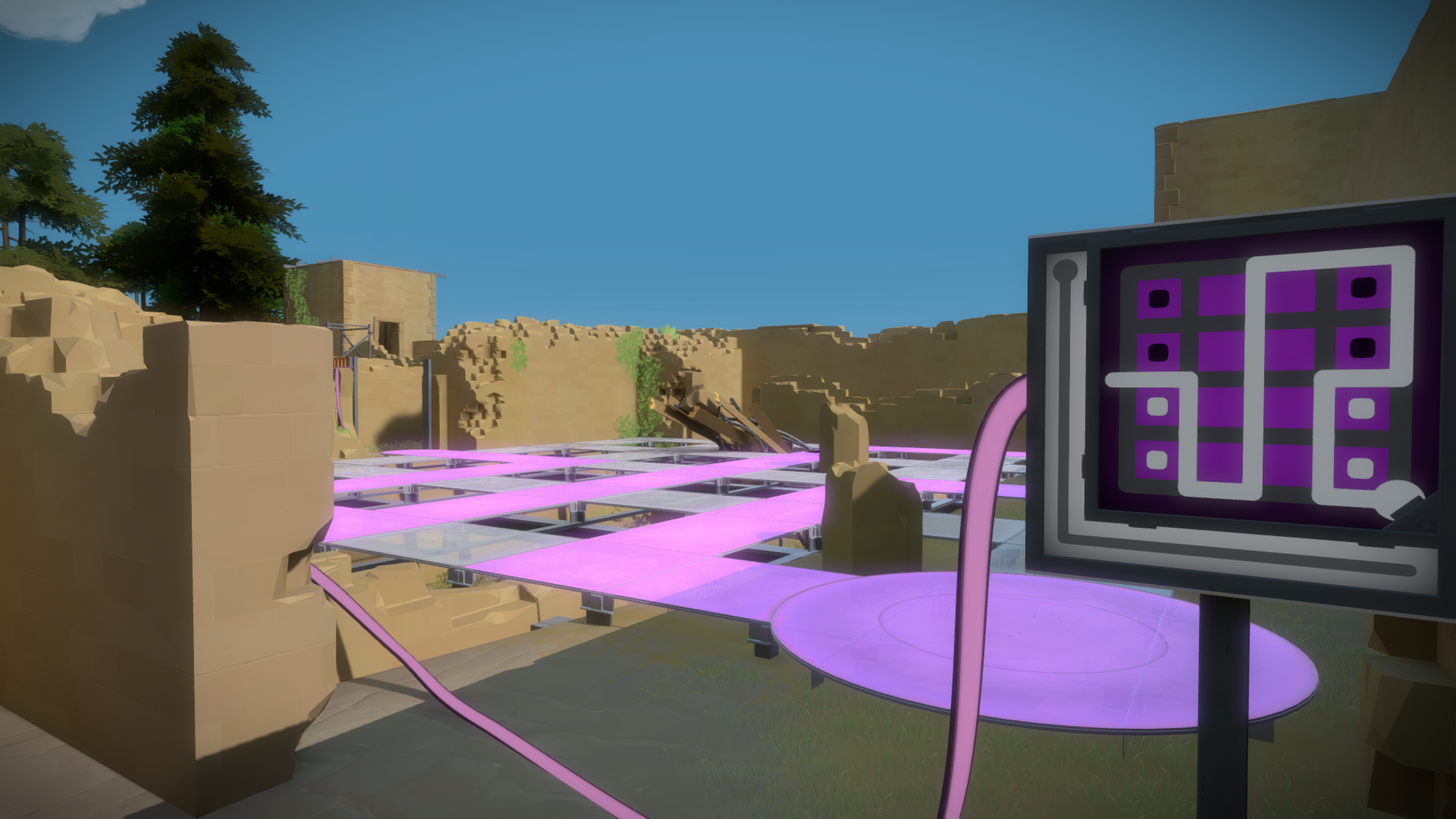

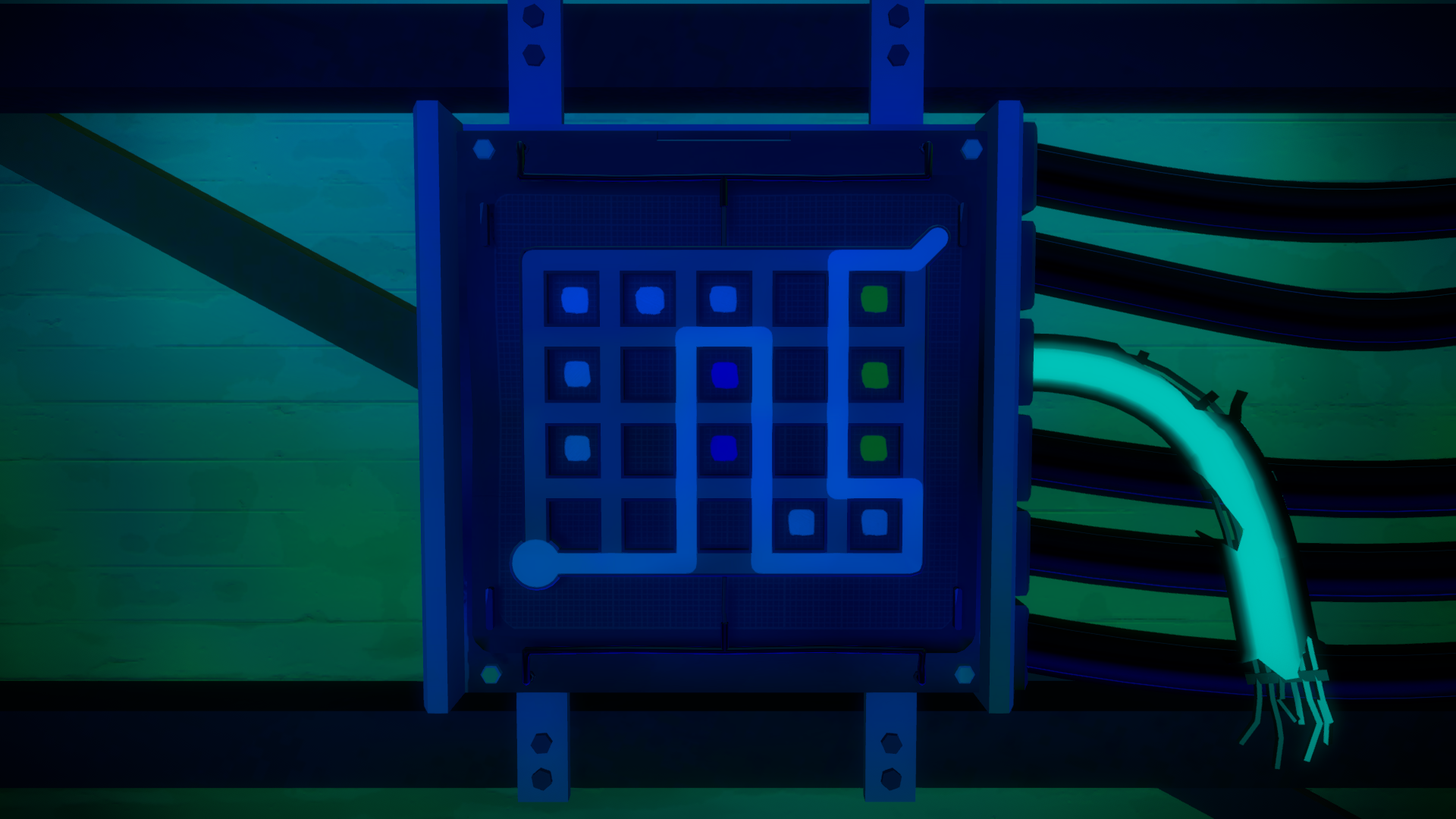

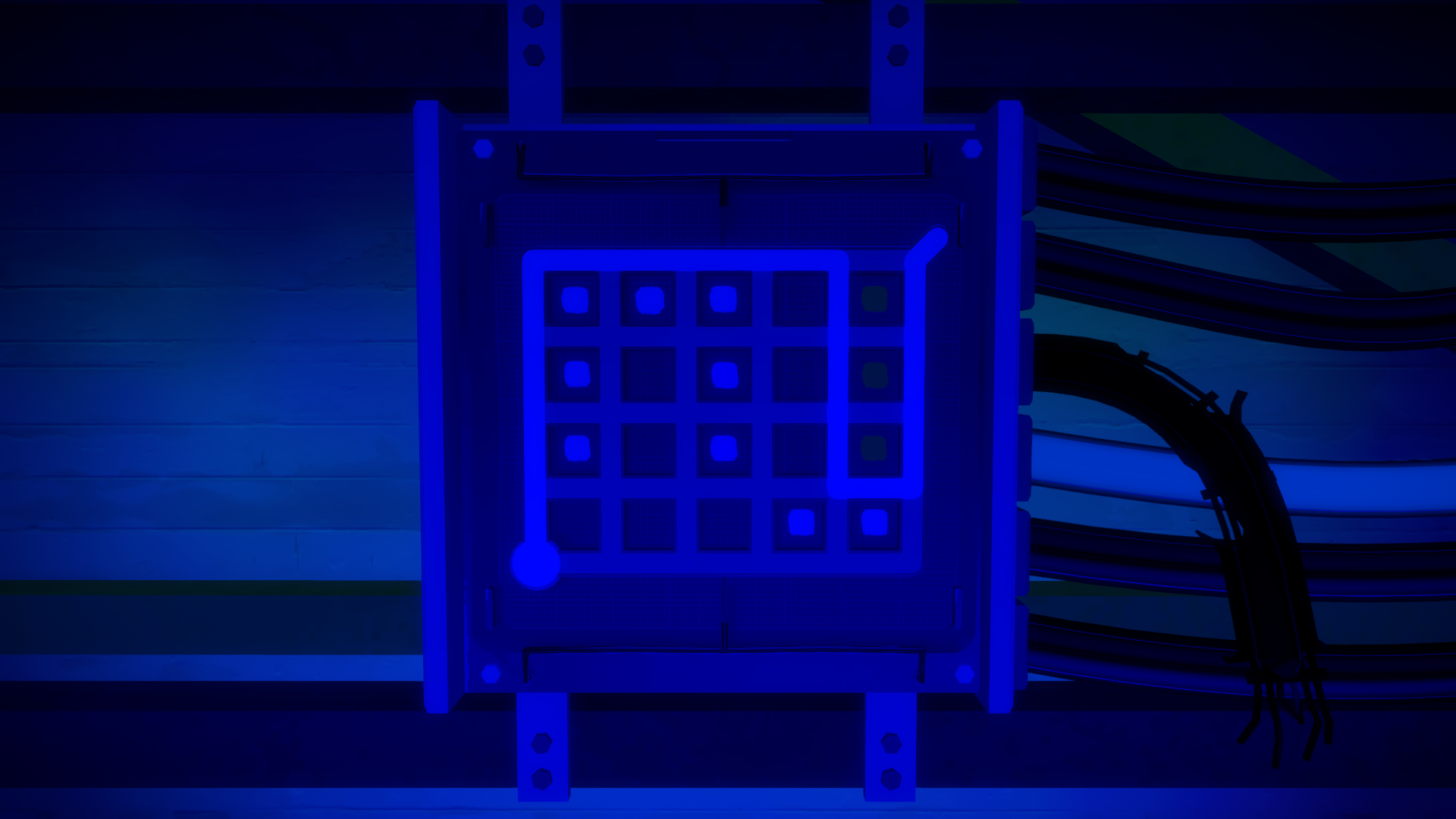

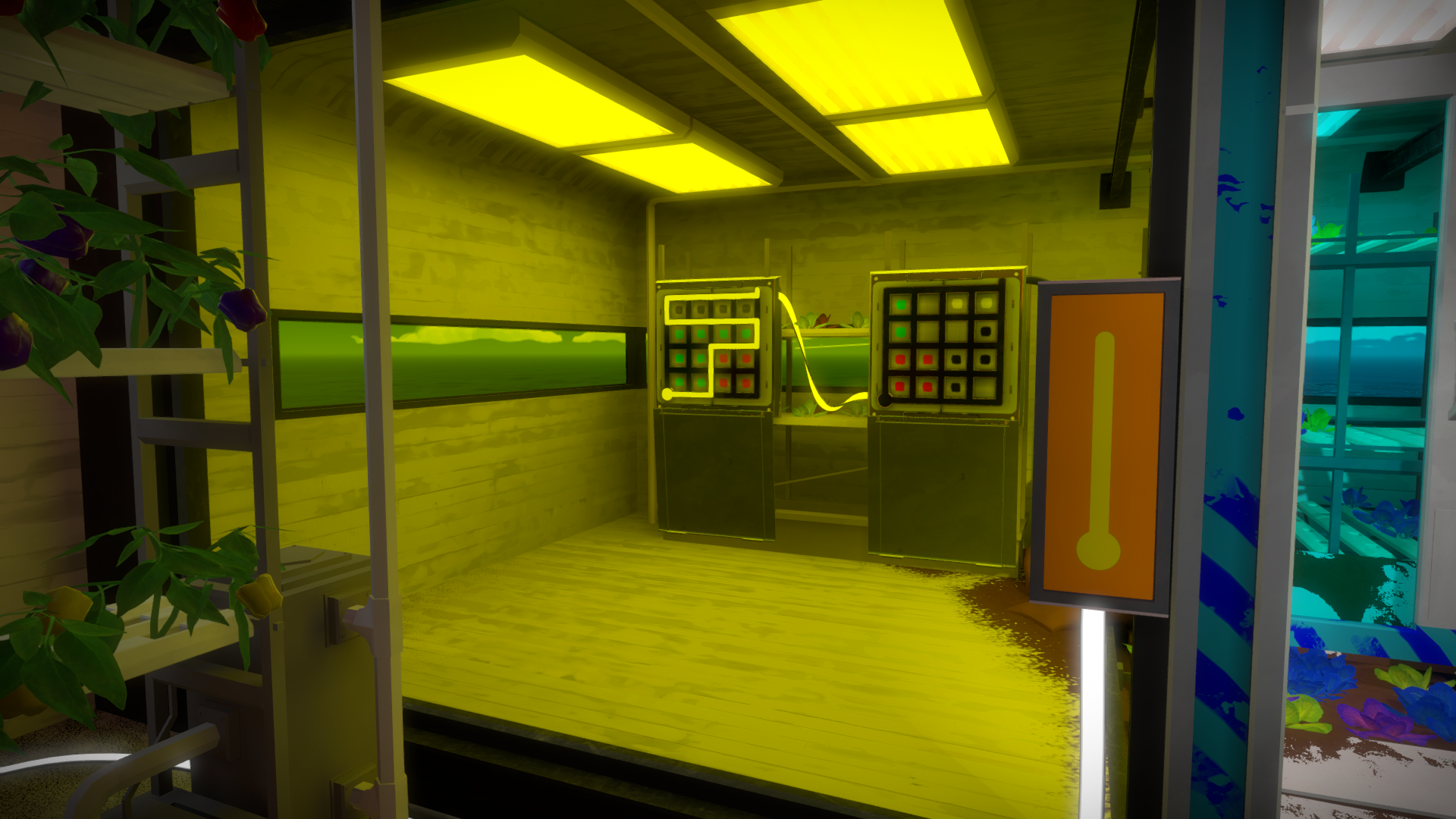

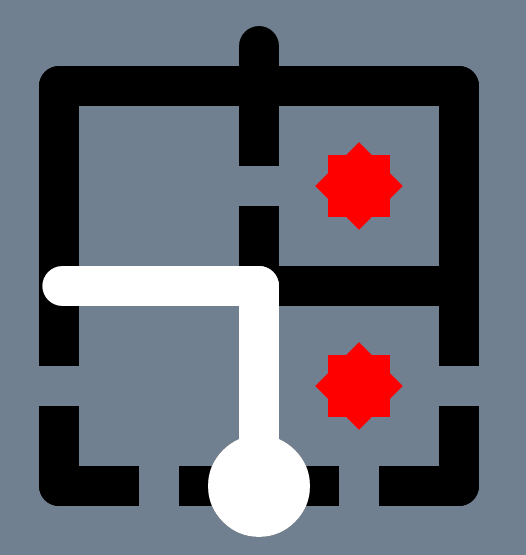

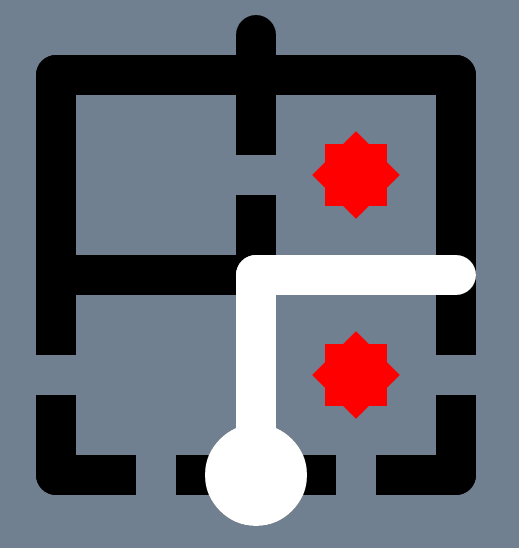

The series of puzzles in the image on the right assumes that the player has understood the rules of the puzzles on the left and introduces certain blue squares as an extra element of difficulty, which obeys another implicit rule of operation. Source: Thekla / Author.

In this sense, The Witness involves a form of propositional knowledge that is never linguistically articulated. Although never formulated as sentences, the rules inferred by the player have determinate truth conditions and generality, which justifies treating them as propositional in content, even if not in form.

I. ii. Formal puzzles and Empirical puzzles

The player formulates hypotheses (for example, that a certain symbol imposes a restriction, or that a certain spatial relationship matters) and tests them in the point-and-click intervention spaces of the game world, which function as empirical testing spaces. When a solution based on a rule hypothesis works consistently in different contexts, the player's belief about that rule gains justification. Interestingly, as with empirical tests in real sciences, it is often not easy to ascertain whether a hypothesized rule is "true" or whether it worked by coincidence, while there is another rule behind it. In general, the puzzles in this game can be categorized as follows:

- Formal puzzles: these can be solved using the syntactic rules governing the symbols on the panel. Example: the puzzles in the previous image, which can only be solved by considering the Tetris Block rule (you must use the line to draw the shape of the Tetris icon, and subtract yellow squares from the icon proportional to the number of blue squares on the panel).

- Empirical puzzles: these require the player to investigate the environment around the panel and relate the space of logical possibilities on the panel to visual or auditory elements outside the panel, including the color and angle of the lighting falling on the panel, or even trees, branches, and other objects that can be visually related to the maze puzzle.

Examples of empirical puzzles in The Witness. In these cases, solving the puzzles requires taking into account environmental factors, such as musical patterns (mixed with noise), reflection, lighting, shadow, representation, point of view, overlapping, and symmetry. Source: Thekla / Author.

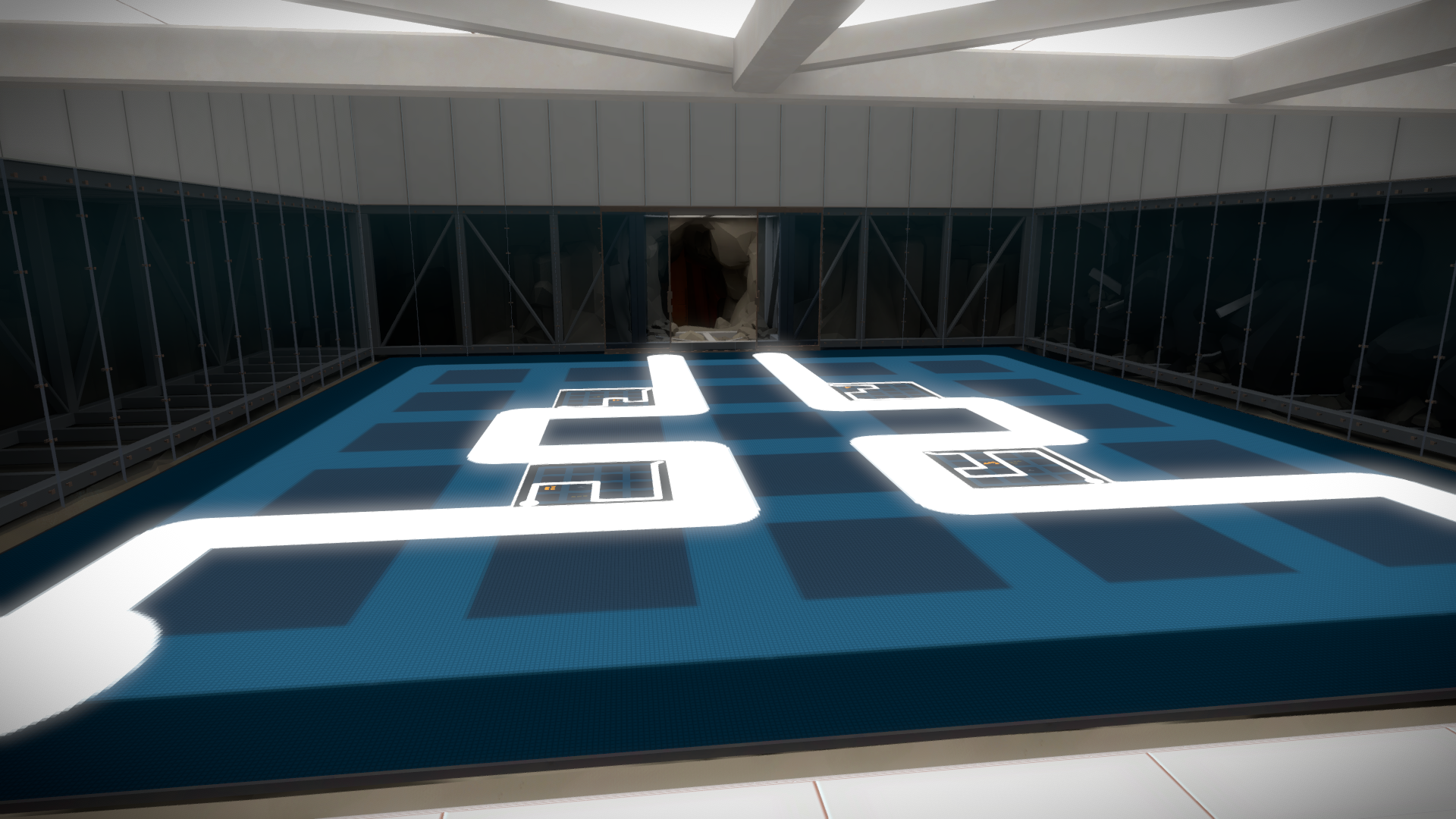

Several formal puzzles in The Witness do not have a single solution; they are non-linear puzzles, a concept discussed by Josh Bycer in The Philosophy of Video Game Puzzle Design here at SUPERJUMP. Although the resolution of formal puzzles is independent of the experience within the environment, in some cases, there are formal puzzles whose possible solutions directly affect movement within the environment, as each solution will result in the construction of a bridge that can provide access to different areas. Furthermore, there are formal puzzles whose solution directly affects a higher-order puzzle (usually represented by a larger-scale maze puzzle).

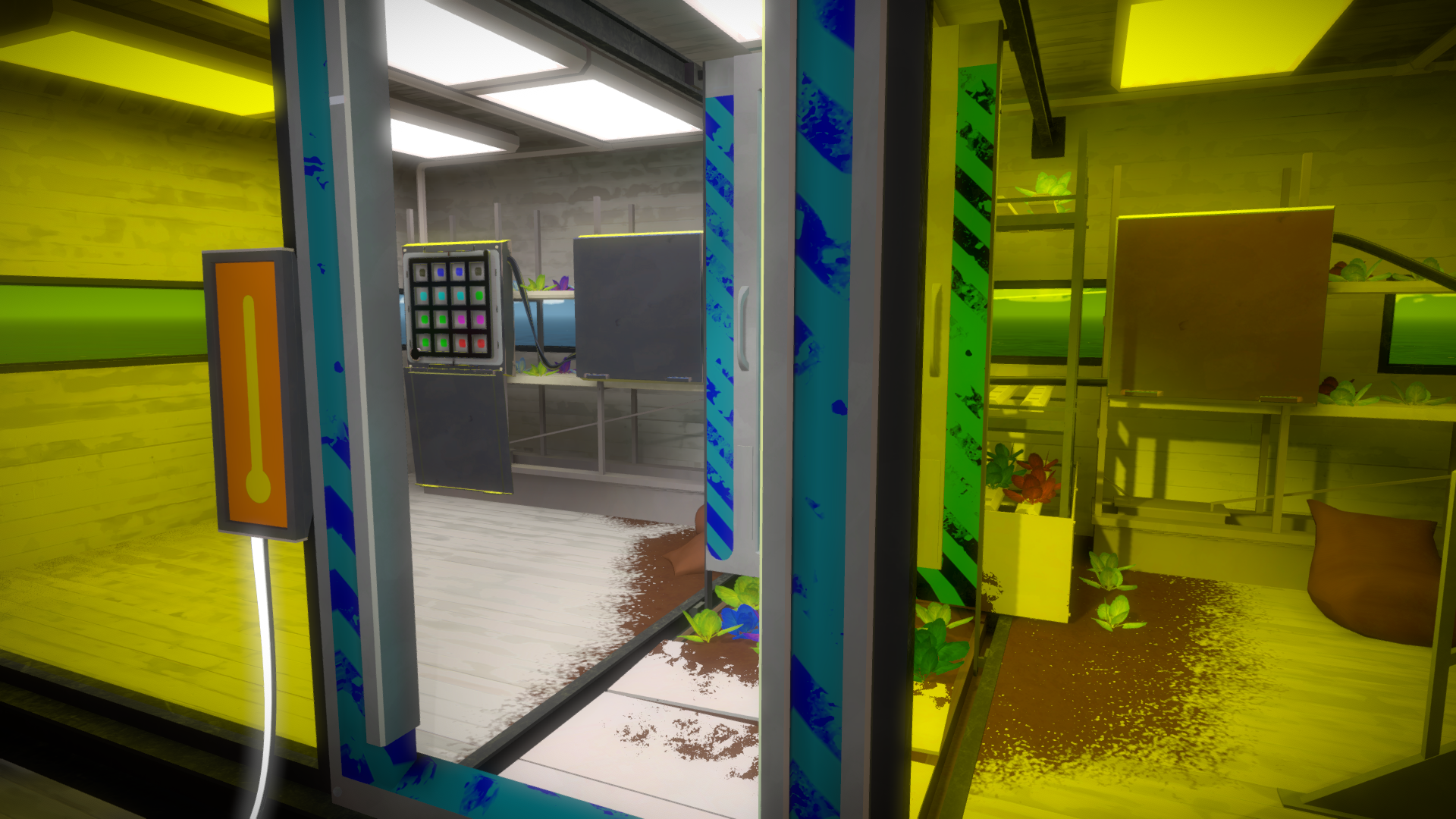

Examples of puzzles with possible solutions that result in different bridges that can provide access to a certain area. Source: Thekla Inc. / Author.

Examples of maze puzzles directly related to other maze puzzles. The example on the right is a metapuzzle. Source: Thekla / Author.

In my piece at SUPERJUMP from 2022, The Reasoning Behind Video Game Puzzle Design, we discussed the differences between deductive, inductive, and abductive reasoning in puzzles. The empirical puzzles in The Witness frequently require inductive or abductive reasoning; that is, they presuppose experimental testing of hypotheses or an investigation of the function of certain objects or effects in the scenario. Let's take as an example the puzzles involving colored stones on the panels and colored lighting in the scenario. In a scenario with this type of puzzle, the player will easily infer that there is something intentional in the emphasis on rooms with colored lighting. Upon realizing that the colored lighting modifies the colors of the stones on the panels, the next step will be to test the hypothesis that this is part of the puzzles in that area.

Puzzles involving colored stones and colored lighting. Source: Thekla / Author.

On the other hand, in the case of formal puzzles, once the rules of the symbols on the panels are known, deductive reasoning (typical logical-mathematical reasoning) is all that is needed to solve them. Formal puzzles in the game can, in principle, be modeled within a Boolean or constraint-satisfaction framework. Consider the equation "A v B". Assuming the classical definition of "v" (or), this equation is not satisfied if A = false and B = false, but it can be satisfied by three choices of values: (1) A=true and B=false; (2) A=false and B=true; (3) A=true and B=true. Logical equations like this can be mapped onto the language of maze puzzles.

Starting from a subset of the symbols (like Suns) used in The Witness, Chris Patuzzo developed an interesting method for drawing a parallel between the formal mechanics of the game and Boolean Satisfiability (SAT), in Reducing Boolean Satisfiability to The Witness (MakerCasts, 2016).

The way to solve a SAT problem is by choosing between true and false for each of the variables in the equation. There's a notion of 'choice'. What does it mean to 'choose' something in a Witness puzzle? What's the corresponding action for choosing? Well, the only influence a puzzler has over a Witness puzzle is to choose their path from start to finish. Do I go North, East, South or West at this junction?

So perhaps we could model variables as forks in the road that the puzzler must choose between. Taking the left fork could correspond to A=true and the right fork could be A=false. Now let's try to put this together with our Suns idea. Let's invent a red Sun to represent the first clause. In our SAT problem, if assigning A=true satisfies the clause, we should design our puzzle so that the Sun is paired up. If they choose to go right, the clause has not been satisfied so this should be an incorrect solution to the puzzle:

— Chris Patuzzo (MakerCasts, 2016)

Left panel: Fork representing A=true. Center panel: Fork representing A=false. Right panel: Stacking forks. Source: Chris Patuzzo (MakerCasts, 2016).

In this first section, we discussed how logic and knowledge work in The Witness to solve puzzles, but the gameplay experience is not limited to that. Open-world exploration allows the player not only to solve puzzles in different orders, but also to freely interpret the traces of different historical periods scattered across the Island.

II. Archaeological Interpretation

From a first-person perspective, the player is projected as an idealized observer walking through a virtually static world; their avatar (with a human shadow) cannot jump or directly touch objects in the environment. In this sense, The Witness provides a dense and contemplative experience of an extended present, one that is largely detached from narrative futurity, as well as vestiges of a past without explicit chronology. In this context, Ian Bogost's reading of the role of the player fits perfectly: "In videogames, the player’s hands operate the lost instruments of the designer’s tiny secret society. A player is the archaeologist of the lost civilization that is the game’s creator" (quoted in Kotaku, 2010). Bogost’s metaphor of the player as archaeologist resonates not merely at the level of game mechanics, but at the level of epistemic posture.

The presence of petrified human figures reinforces this archaeological logic. These figures, frozen in postures that suggest everyday activities, evoke archaeological sites such as Pompeii, where bodies function as material traces of lived practices rather than as narrative characters. In The Witness, these petrified individuals serve as silent evidence of past actions, gestures, and intentions. Their placement within the landscape invites conjectures about what people once did in those locations, how they interacted with the environment, and what kinds of practices were considered meaningful. Yet, as in interpretative archaeology, such conjectures remain interpretative rather than demonstrative. This stands in sharp contrast to the epistemic regime governing the panel puzzles.

Petrified human bodies in the ruins of Pompeii. In 79 CE, the Vesuvius volcano in Southern Italy erupted, destroying settlements around it and taking the lives of up to 16,000 residents. Sources: Peter's big adventure / The Colector.

A petrified modern domestic dog and petrified people who apparently lived in different historical periods. Source: Thekla / Author.

Outside the panels, the player is no longer confronted with well-defined problems whose solutions are mechanically verifiable. Instead, the environment presents itself as a dense field of material traces: ruins, abandoned structures, statues, inscriptions, unfinished buildings, and scattered artifacts whose meaning is never explicitly articulated. The material remains suggest multiple layers of the past, but these can only be contemplated; the player can only reconstruct their meaning through interpretation.

This mode of engagement closely aligns with the principles of interpretative archaeology as developed by Ian Hodder: "an interpretive postprocessual archaeology needs to incorporate three components: a guarded objectivity of the data, hermeneutic procedures for inferring internal meanings, and reflexivity." Interpretative archaeology, as articulated by Ian Hodder within postprocessual archaeology, rejects the notion of material culture as a neutral repository of facts.

A series of paintings and sculptures that can be interpreted as an allusion to human evolution. Source: Thekla / Author.

For Hodder, meaning is not extracted from objects as if it were hidden within them; it is produced through the interaction between observer and material culture. In The Witness, the material culture of the fictional world is intimately linked to the material culture of the real world in which the player and the creator reside. The player’s interpretive freedom is itself historically situated, shaped by modern archaeological and museological ways of seeing. The island is thus not merely interpreted as a past world, but as a past legible through contemporary epistemic habits.

Based on our knowledge of real-world human history, we can interpret the objects (rails, abandoned chairs, drawings, ruins, etc.) in such a way as to reconstruct multiple anthropic interventions throughout the past: an ancient civilization, the settlement of a native tribe, the construction of a medieval village, the establishment of a port with industrial technology, an exploration expedition in the mountains, the appropriation of the island as a tourist destination, etc. However, the game never confirms whether these layers correspond to a linear historical progression, a coexistence of traditions, or a symbolic juxtaposition. In Hodder’s terms, the stratigraphy is meaningful but underdetermined. This underdetermination is not a failure of historical reconstruction, but the very epistemic condition through which the game stages archaeological knowledge.

Architectural structures that allude to a tribal society that lived in trees (left), ruins of an ancient civilization (center), and a medieval castle (right). Source: Thekla / Author.

Typical Renaissance sketches (left); industrial infrastructure elements (center); objects of modern tourism (right). Source: Thekla / Author.

The game's audiovisual production directly engages with real-world island references. Most of the ambient sounds were recorded during a walk around Angel Island in San Francisco Bay. Blow's team also collaborated with a landscape architecture firm, Fletcher Studio, to develop the environments for The Witness. In The Witness: Designing Video Game Environments (2017), Fletcher Studio explains that the Azores archipelago (known as Europe's secret islands) served as inspiration for the game.

The layers of different cultures, from ancient civilizations to the Portuguese monarchy, to present day fishing villages, proved most analogous. Available aerial imagery was collected from the Azores and then collaged together to create a fictional Island in plan, now with topography, beaches, water bodies, etc.

[...]

In the beginning, the island was a cultural tabula rasa. In order to make sense of the existing and constantly introduced structures and spaces, it’s cultural history had to be written. The projective devices that we had developed, were applied to the Island in reverse. The past was divided into three successive epochs, which we termed Civilizations (CIV’s) One, Two and Three. A simple description of each was developed, and then a larger matrix, was produced that related to each in terms of infrastructure, architecture, and landscape. Each of these three categories had their technologies, agriculture, religion, and cultures. Materially, each epoch had its own techniques of building, based on assigned resources and technologies, with each CIV methodologies and products growing more refined over time.

— Fletcher Studio, 2017.

From left to right: evolution of the Island through time; The Witness Island at the time of game publishing. Source: Fletcher Studio / Thekla, 2010-2014.

From left to right: map of Island zones; Island map attached to the boat that serves as a vehicle in the game. Source: Thekla / Author.

Ironically, the meticulous predesign of fictional civilizations does not resolve interpretive ambiguity, but actively produces it. In this sense, the game mirrors Hodder’s critique of positivist archaeology: even exhaustive documentation and planning do not eliminate interpretation. Unlike formal puzzles, there is no possible final reconstruction of the island's history, nor a privileged account that resolves conflicting interpretations; archaeological knowledge remains provisional. Knowledge, in this context, is not measured by correctness but by interpretative coherence.

The Witness juxtaposes two distinct modes of knowledge: formal, rule-governed knowledge and archaeological, interpretative knowledge; consequently, the difference between solving problems and understanding worlds. Although the distinction is analytically useful, the game occasionally blurs that boundary. This tension is central to the metafictional and intertextual elements in the game.

III. Metafiction and Intertextuality

While the formal puzzles and the archaeological reading of the island structure two distinct epistemic regimes within The Witness, the game introduces a third and more reflexive layer of knowledge through its metafictional and intertextual elements. These elements are primarily conveyed through audio logs, short video recordings, and, most strikingly, through the final sequence of the game, which destabilizes the ontological status of the island itself.

The audio logs scattered throughout the island consist of excerpts from philosophers, scientists, artists, and religious thinkers, ranging from Plato and Heraclitus to Simone Weil, Feynman, and contemporary writers. These recordings function as intertextual fragments, disconnected from each other and from any explicit justification within the game. Their arrangement is deliberate, but not instructive: they are neither rewards nor keys; instead, they operate as epistemic provocations. Listening to a quotation about perception, certainty, or illusion after struggling with a sequence of puzzles does not resolve the puzzle retroactively; it reframes the player’s understanding of what they have been doing all along. In this sense, the recordings function less as narrative exposition and more as meta-commentary on the act of knowing itself (in addition to related topics, such as faith and skepticism).

The physicist Wolfgang Pauli once spoke of two limiting conceptions, both of which have been extraordinarily fruitful in the history of human thought, although no genuine reality corresponds to them.

At one extreme is the idea of an objective world, pursuing its regular course in space and time, independently of any kind of observing subject; this has been the guiding image of modern science.

At the other extreme is the idea of a subject, mystically experiencing the unity of the world and no longer confronted by an object or by any objective world; this has been the guiding image of Asian mysticism.

Our thinking moves somewhere in the middle, between these two limiting conceptions; we should maintain the tension resulting from these two opposites.

Werner Heisenberg, 1974

— Audio log: Heisenberg on Pauli (The Witness Wiki)

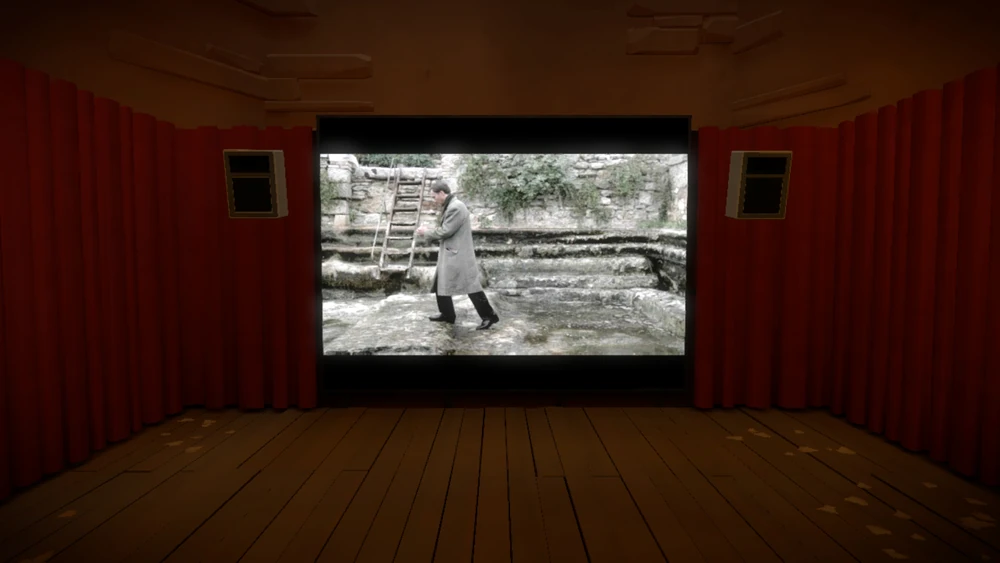

A similar function is performed by the short video recordings accessible in certain locations. These videos show real people (often scholars or artists) speaking directly to the camera about themes such as attention, learning, perception, and the limits of understanding. The abrupt shift from the stylized, silent world of the island to these unmistakably real audiovisual artifacts creates a moment of ontological friction.

The player is reminded that The Witness is not merely a fictional world to be decoded, but an object designed and embedded within the epistemological problems discussed in the real world. This ontological friction is revisited and developed in the final part of the game, where the fictional and the real progressively merge until the player reaches the creator's real world.

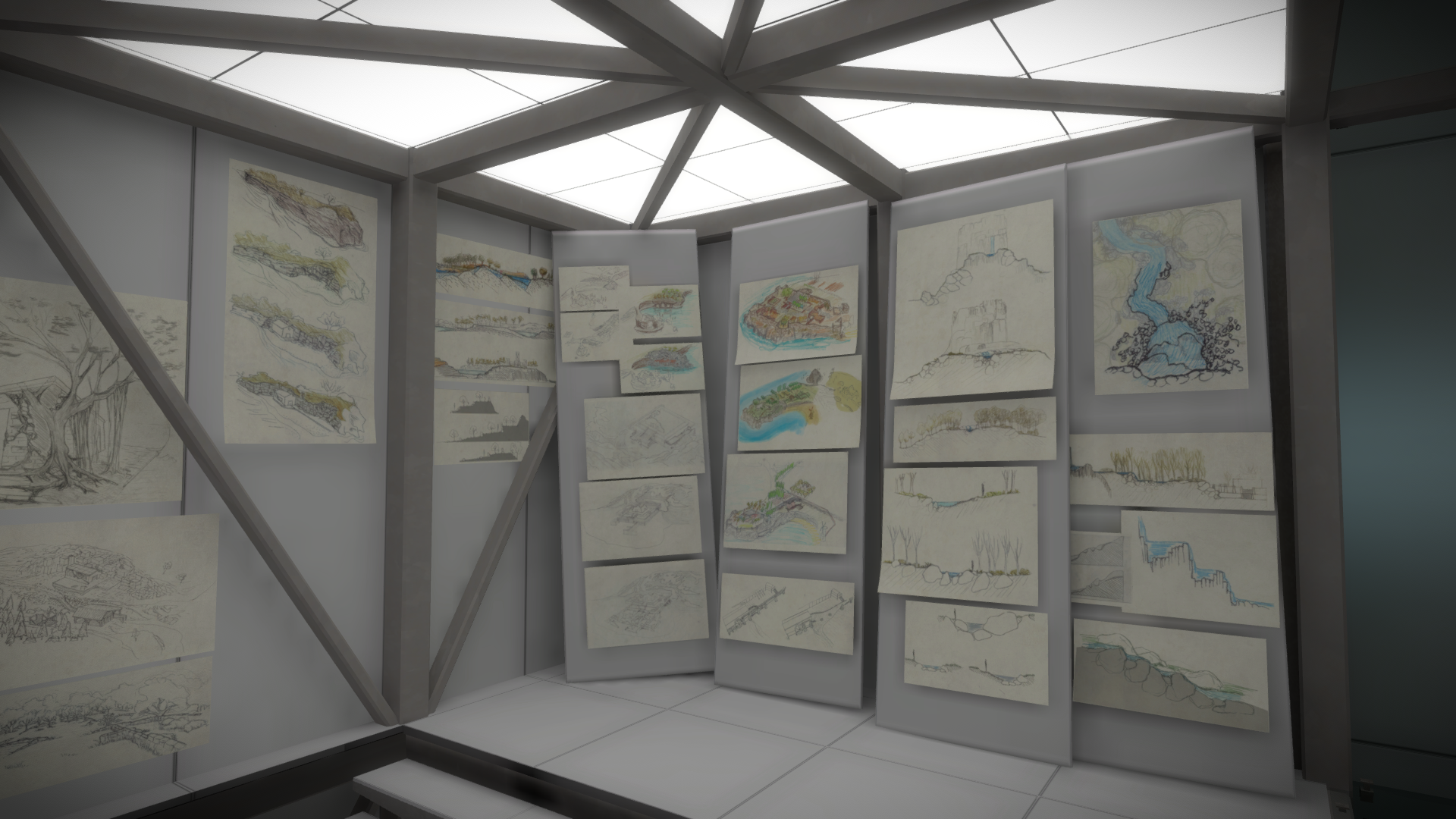

Images from the final part of the game, featuring footage and design sketches of the island and some puzzles. Source: Thekla / Author.

The ending can be understood as a form of metadesign disclosure. Throughout the game, the player has been encouraged to infer rules, reconstruct histories, and interpret traces, all while remaining within the diegetic boundaries of the island. The final sequence retroactively reframes this entire process: knowledge, here, is no longer about mastering mechanics or reconstructing fictional pasts, but about recognizing the conditions under which understanding takes place. The conclusion exposes the player to the limits of comprehension, forcing them to recognize the structures through which meaning becomes possible in a fictional world.

This essay set out to show that The Witness is not merely a sophisticated puzzle game, but a carefully constructed epistemic experience in which different modes of knowing are staged, contrasted, and ultimately problematized. The game operates as an experimental space in which the player is invited to enact, test, and reflect upon distinct epistemological attitudes, temporality, empirical perspectives, types of logical inference, and levels of logical complexity.

In the first section, we examined how logical knowledge structures the core gameplay. The panel puzzles require the player to infer abstract rules, formulate hypotheses, and justify beliefs through repeated testing. Although these rules are never linguistically articulated, they exhibit propositional structure, generality, and determinate truth conditions. The second section shifted focus from formal problem-solving to environmental interpretation, framing the island as an object of archaeological inquiry. Here, knowledge is no longer validated by mechanical correctness, but by interpretative coherence. In the third section, we examined how metafictional and intertextual elements further destabilize epistemic certainty. The player is prompted to recognize not only what they know, but how their ways of knowing have been shaped.

By intertwining logic, archaeology, and metadesign within a single interactive framework, the game provides a dense space for reflection on epistemic questions and stages a progression, not toward truth, but toward epistemic self-awareness.