The Virtue of Alienation

Exploring how games alienate the player, forcing us to contemplate why we wish to escape into these virtual worlds

Last winter, I was playing Chrono Cross, imagining how I might explain its complicated battle system to the uninitiated.

“See, you have two types of attacks, physical and magical, and all of your magic attacks are discrete items… See, you can do physical attacks in three tiers of strength with inversely corresponding accuracy ratings… See, you need to build up a meter by landing physical attacks, and once it’s full, you can use more powerful special attacks…”

Each element in the system feeds into another element, so the whole construction is closed off; there’s no intuitive entry point. It’s so needlessly complicated, so videogame-y, that it feels like it actively repels the player.

That’s not to say it’s bad, though. It’s just alienating, in the Brechtian sense — constantly reminding you that its world and characters are fake, that the experience is artificial. Its battles are so abstract that it becomes difficult to recognize them as battles instead of collections of intersecting data.

Take those physical attacks, for example: Why, outside of the self-evident necessity required to make the battle system work, do your attacks have an inverse relationship between strength and accuracy? Why are you only able to access magic by landing physical attacks? Why are you only able to use a spell once per battle? Why are spells equippable items?

There isn’t really an answer to those questions; these things just are. It’s a game, full of systems that are ends unto themselves. Given Cross’ relationship to its predecessor, Chrono Trigger, this approach feels radical. Trigger bucked trends upon its release, abandoning random encounters and the need for a separate battle screen, making its fights feel more grounded and integrated with the rhythm of its exploration and narrative. Cross rebels against Trigger’s rebellion in mechanics and in its story.

In Chrono Trigger, you use time travel to avert disaster, and the game concludes with a happy ending. But Cross argues that your time-hopping shenanigans in the first game were actively harmful to the fabric of the world, causing dimensions to split and great cities to fall into ruin.

This new perspective on Trigger’s events has given Cross a complicated legacy. Cross’ refusal to work within the narrative bounds established by its predecessor angered many fans of the first game. While its reconsideration of heroic events as destructive might be difficult to swallow, it doesn’t feel superfluous. It’s part of a larger design philosophy, one centered not around immersing you in a different world, but around emphasizing your difference from it; the game insists on its own inscrutability, the coherence of its own reality as something parallel to and inaccessible to us.

Even without considering Trigger’s events, Cross still forces you to play as a villain — partway through the game, you’ll swap bodies with the chief antagonist, an anthropomorphic “demi-human” who is shunned by other characters.

When I reached this moment in the game, it immediately reminded me of another JRPG: the GameCube cult classic Baten Kaitos: Eternal Wings And The Lost Ocean. In it, you’re cast as a Guardian Spirit, accompanying the main character Kalas on his journey to avenge the deaths of his grandfather and brother. Then, midway through the game, Kalas reveals that he’s secretly been collaborating with the game’s antagonist, and promptly leaves the party; this moment is accentuated by a visual effect of a CRT television turning off. You’re then bonded with a different character to continue the story, picking up the pieces after Kalas’ deception.

In both games, these twists radically place your actions in a different context and force you to reconsider your role as a player within the game world. You might hold the controller, but are you really in control?

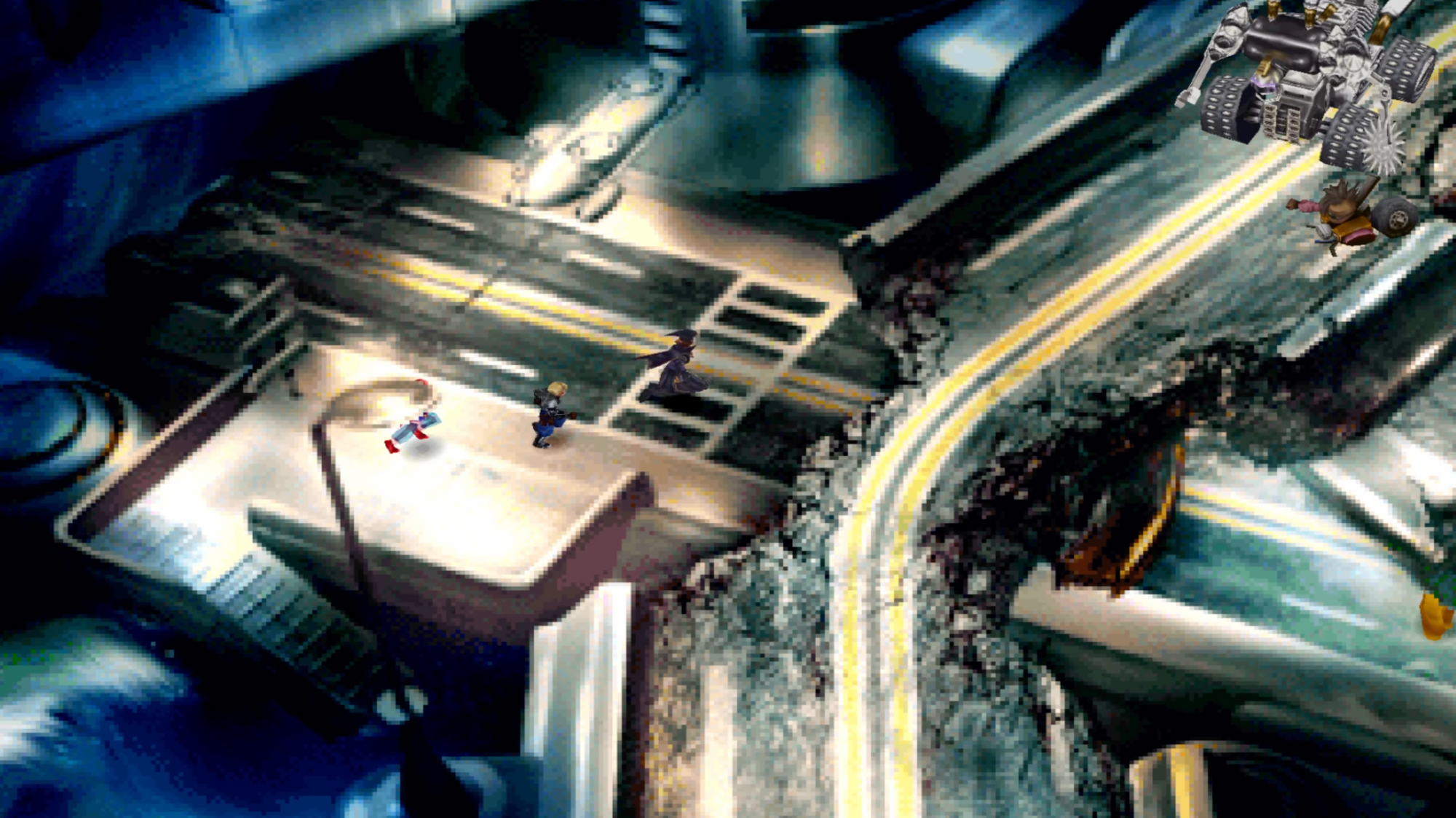

While Baten Kaitos never directly references Chrono Cross, the similarities extend beyond their shared story structure. Both games feature experimental battle systems that treat attacks as consumable items — Cross with its Elements and Baten Kaitos with its Magnus cards. There are two games that send you through multidimensional rifts to different locations. They both take place in a world made up of discrete islands, both sharing key staff members — Yasuyuki Honne and Masato Kato held important roles in the development of both games — and made use of pre-rendered background environments.

This last design choice makes both games feel somewhat distant, like playable dioramas. Their environments show us houses we cannot enter, and areas of cities and forests that we cannot access; they are simultaneously teeming with life and empty of interactable elements. Unlike a modern open-world game, we cannot go everywhere; we are not native to these virtual worlds.

I completed Baten Kaitos while I was deep in a depressive hole, needing something to take my mind off of my reality. When I finished the game, the last thing I saw before I turned off the game was an image of my party members, waving at me through the screen as I — the foreign Guardian Spirit — returned to the real world.

It felt rewarding, but also melancholy; the game acknowledges its own reality as a game, a distant and unreal world that I can only experience through a constrained, predetermined track. Chrono Cross’ broken, split archipelago feels similarly distant and sad, home to stories of environmental destruction and institutional oppression. Both games alienate the player through their systems, stories, and visual design, letting us in but keeping us at arm's length. They remind us we cannot remain in the virtual world. They force us to consider why we want to escape our own lives. And, maybe, how we might change them.