Chrono Trigger/Chrono Cross and Temporal Ontology, Part 1

Time Travel and Linear Time vs. Branching Time

If time travel is possible, what is the difference between time travel in a temporal conception in which there is a single timeline and in a temporal conception in which there are multiple timeline branches? This is one of the fundamental questions for the level design and narrative design of Chrono Trigger (1995) and Chrono Cross (1999), and here I will analyze these questions in the light of the philosophy, temporal logic, and lore of these games.

For this article (and also its sequel), I will have to make references (spoilers!) to specific moments of the lore at different moments in the history of Trigger and especially Cross. In parallel, I will use some concepts from two areas of philosophy, ontology, and logic, but more specifically from temporal ontology (which studies what time is about) and temporal logic (which studies mathematical models for formal structures of temporal concepts). But don't worry, the terms here will appear in a very simple way, and I'll try to approach them in the most didactic way possible.

Like Chrono Trigger, its successor Chrono Cross works with the concept of travel, but in a different “ontology of time”. In philosophy, this means that Cross works with a different conceptual background to define what time is (or what it means). I will analyze this issue in the following topic, showing how the first game involves a linear time conception, while Chrono Cross assumes branching-time in multiple timelines.

This article will be continued in a future text, also involving Ontology, where I will analyze the question about the identity of Cross's characters in this context. That is to say I will analyze what is the basis for sustaining that all "Serge" (protagonist of Chrono Cross) in different lines of time are, in fact, one and the same being/entity; thus all “Serge” have the same “identity”. It will be a very nice discussion, which presupposes the content of this essay, and tackling it here all at once would make the text too long.

The problem of inconsistency with temporal ontologies in Chrono Trigger

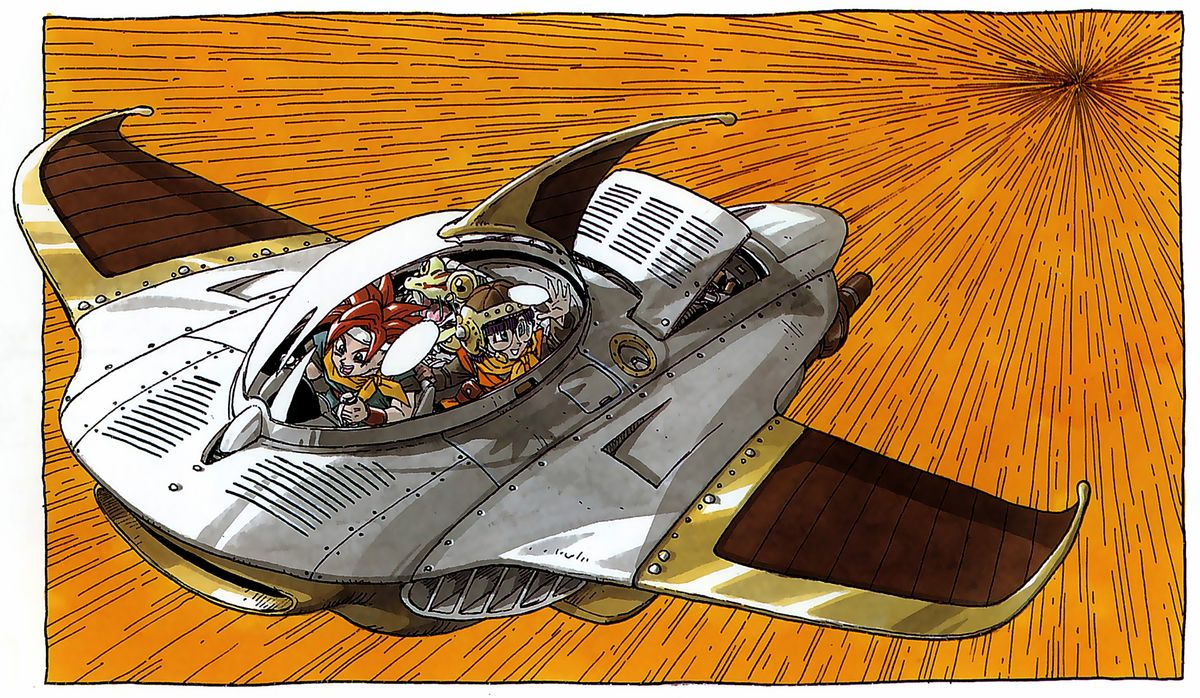

In Chrono Trigger, in principle, there is a single timeline, which means that if you travel to the past, your actions will have consequences for the present and future of that same timeline. Thus, in Chrono Trigger, the heroes of time try to make changes in the past and present, via time portals and the Epoch spaceship, in order to prevent a creature called Lavos from destroying the world in the future and leaving humanity in a post-apocalyptic context where we meet the iconic Robo for the first time.

See that the premise assumes that once the past is significantly altered with respect to Lavos, the dystopian future would no longer exist, and all the events that followed after his attack on the planet would be rewritten in the Chrono Trigger story. In other words, this premise is incompatible with a time ramified by temporal possibilities. This is because, in the case of there being a branching time, the dystopian future would not cease to exist by changing the past, but there would only be a bifurcation: a timeline in which Lavos destroys the world and another in which the world is not destroyed by him.

Chrono Trigger. Source: Nintendo Blast.

There are several problems related to the concept of time travel in a single timeline ontology. The best known is perhaps the Bootstrap Paradox, a very strange type of phenomenon in which it would be possible, in this scenario, for a certain thing to originate by itself (it is itself the cause and effect of something). Imagine, for example, that you hit a billiard ball, and that ball at one point traveled in time and hit itself in the past, deflecting its course, this would mean that what caused the ball to change course was itself.

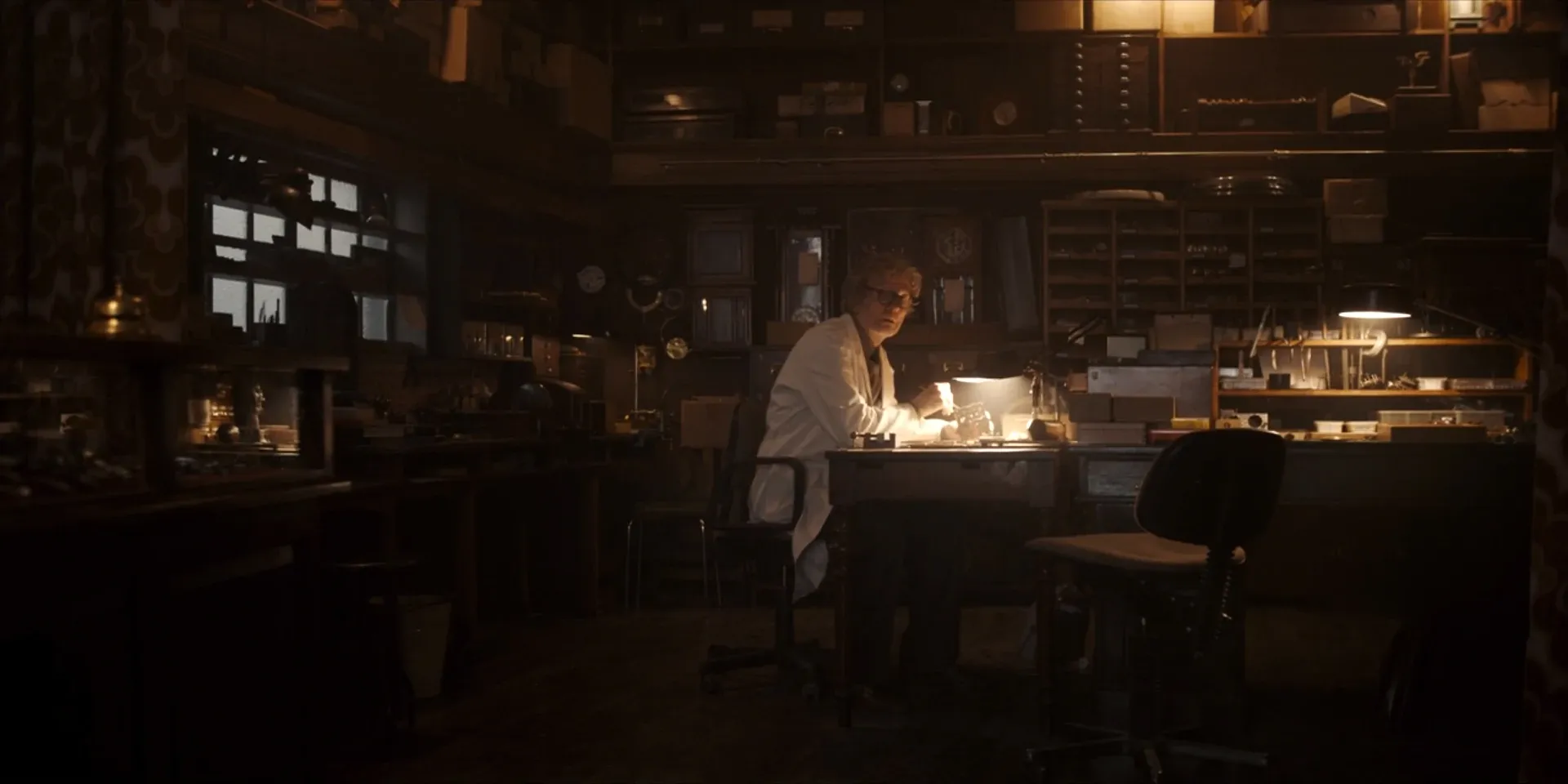

Dark, a Netflix series directed by Baran bo Odar, provides a good example of how strange this is. In this series, a watchmaker builds a time machine based on a book received by a traveler from the future, only that book is authored by the watchmaker. In other words: who invented the time machine? In this context, it does not have an inventor, it is the cause and effect of its own existence, because although the book that teaches how to make the machine was only published after the machine was built, it was only built because the book had already arrived to the watchmaker in the past, so it is a book without an author.

Left: H.G. Tannhaus' Clock Shop, Dark. Source: Dark Wiki. Right: Time travel cause-effect problem. Source: Nintendo Blast.

Chrono Trigger tries not to give visibility to problems of this nature, but the truth is that they can occur in that context. One way to avoid this is to adopt a branching-time ontology. In this case, when you travel to the past, you don't change the future, but rather create a new timeline where things played out differently. This premise is used, for example, in the anime and visual novel Steins;Gate and also in Chrono Cross. It turns out that we have a small problem: when putting Trigger and Cross together, there is an ontology inconsistency, as Cross uses branching ontology; but Trigger does not. I'll explain.

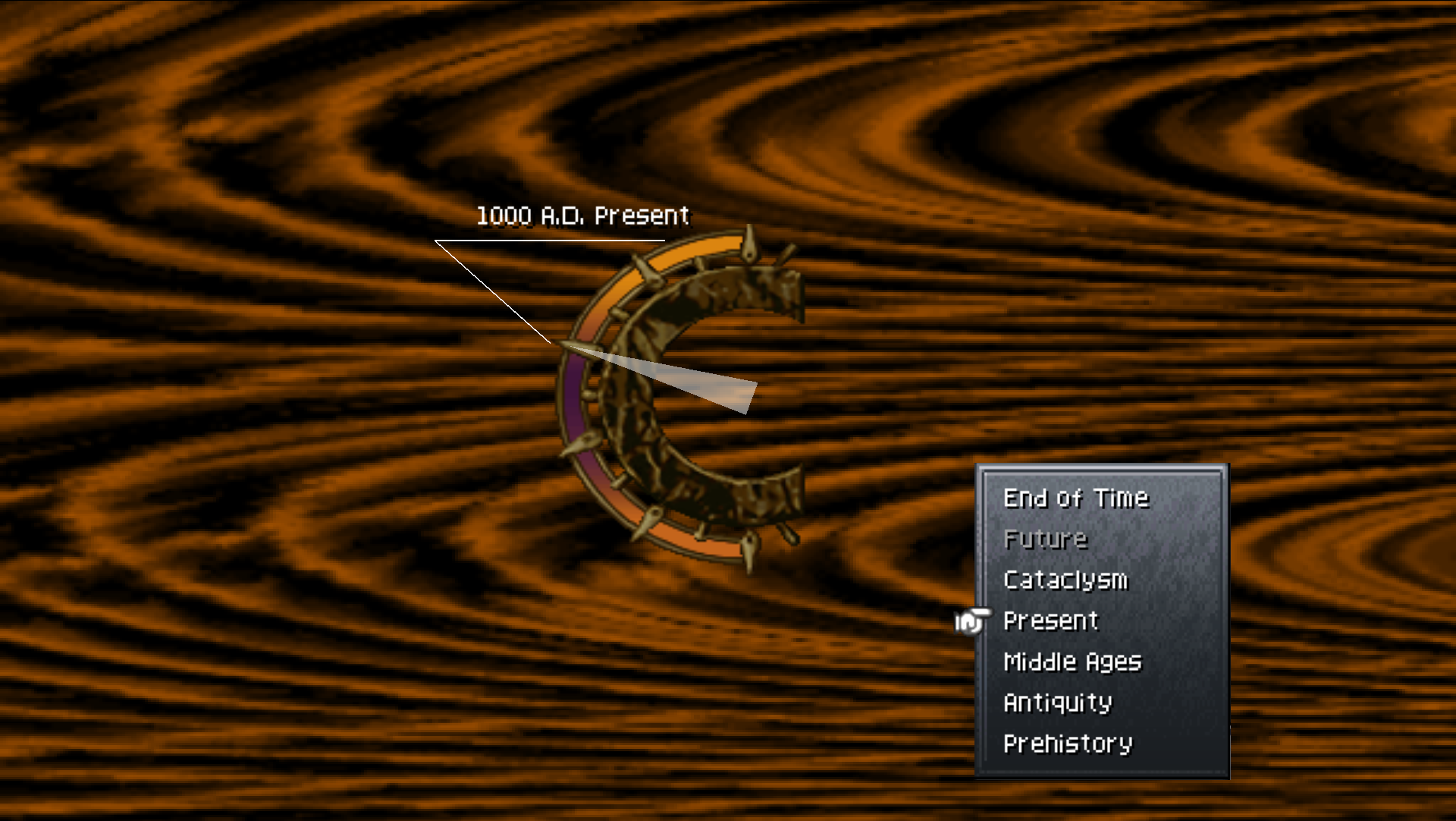

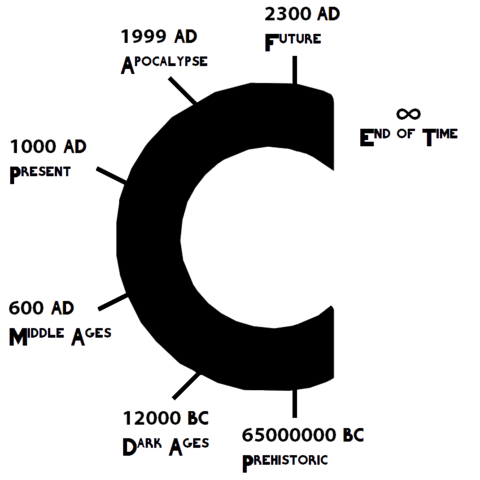

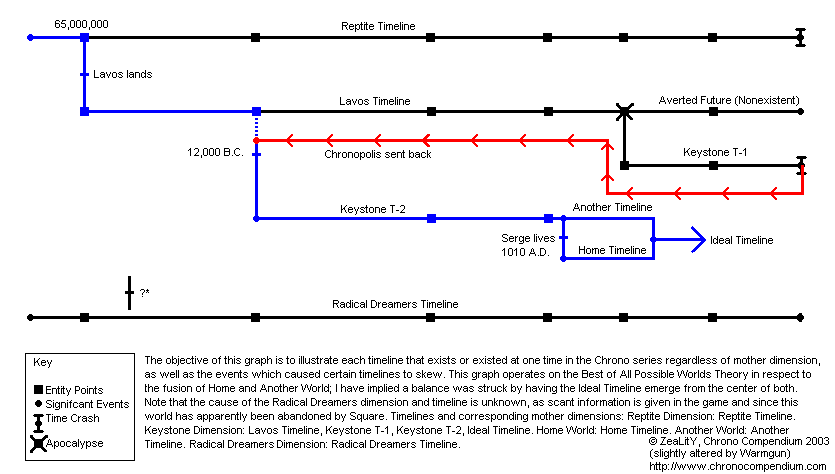

We can conceive of two timelines in the remote past (65 million years B.C.) of Trigger/Cross: a timeline in which an alien form named Lavos collided with Earth, and one in which it did not collide with Earth. In the first case, it is the main line of the game, in which humans reigned over the Earth until reaching its dystopian end. In the second case, it is humanoid reptiles that reigned over the Earth, resulting in an entirely different series of events. The incompatibility is because we also know that Lavos is defeated and that definitely changes the future, after all, that's the purpose of the game (Trigger's linear timeline below).

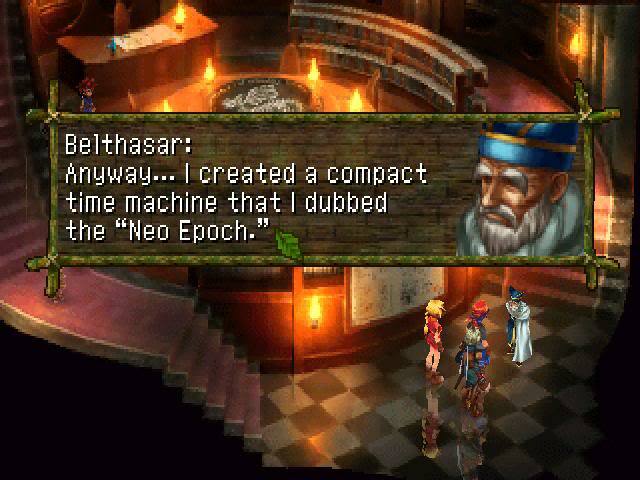

One might assume, “well, but maybe there are two futures. Defeating Lavos only branched out into a non-dystopian alternate future.” It turns out that at the end of Chrono Trigger, there is a character, named Belthasar, who is sent back to his time in the future after Lavos' defeat, but he doesn't go back to the dystopian future, but to the new future that was created, thus proving that that dystopian future no longer exists (i.e., it presupposes a linear/single time ontology).

In my view, this inconsistency can only be circumvented if it is admitted that the dystopian future exists (it did not cease to exist), making explicit a branching-time ontology, and we must still seek another explanation for why Belthasar ended up in another future. A solution of this type can be analyzed in Chrono Cross, but that would be another long text. For now, we will just understand the difference between these ontologies and how Trigger and Cross are related (below is a diagram of the branching timeline).

Branching time ontology and the temporal reworking of the Chrono series in Chrono Cross

Chrono Cross does not contradict any of the events of Chrono Trigger, on the contrary, it is consistent with everything reported there. This is because Masato Kato (director and writer of Chrono Cross) has spent many years thinking about this “indirect continuation”, having worked as a writer for both games. But why an “indirect continuation”? Because the entire story of Cross takes place in another timeline, or rather, in other timelines, and this concept of multitemporality is already brilliantly didactic, having been exposed right at the beginning of the narrative.

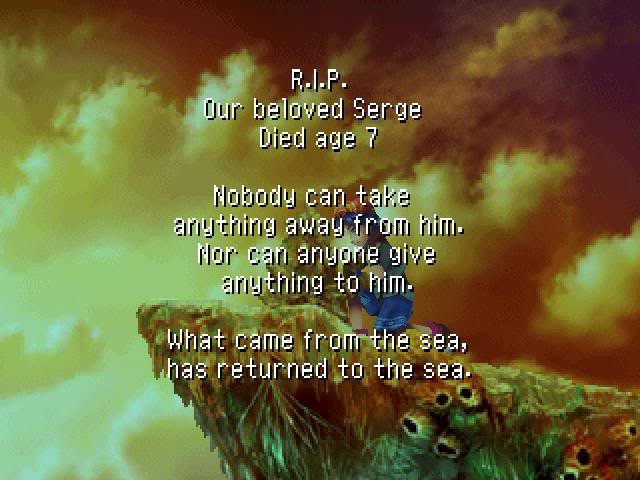

In the first moments of the game, Serge, the protagonist of Chrono Cross, finds an interdimensional passage that takes him to a parallel timeline. There, he finds out that he died 10 years ago (in that timeline), in 1010 A.D., so this is a temporal bifurcation. There's a timeline where Serge drowned and 10 years passed with different events stemming from that fact; and there's a timeline where Serge didn't drown, his father managed to get him back, and the next 10 years went by with some differences stemming from that. All events before the sea voyage, which forked the timeline, occurred identically on both lines; that is, they were one.

Note that, in this case, no matter what Serge does in his timeline (Home World), it will not change the other timeline (Another World) at all. So, see that the premise is different from Trigger, there is no way to change the future, at least not absolutely, but only relative to a timeline. But what is the connection of this story with Trigger? Are any of these timelines the unfolding of Trigger's? So… not really, it's also a timeline parallel to that of the first game.

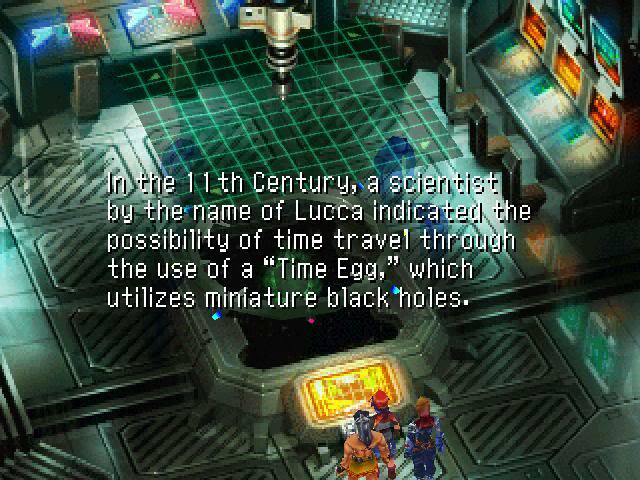

Consider the scenario where Trigger's dystopian future did not occur and Lavos was defeated. As already said, the character Belthasar was sent to this future. What wasn't developed in Trigger, but rather in Cross, is the fact that in this future he began to undertake time travel research at a place called Chronopolis, and found that Lavos still existed in a multitemporal form, and was still a threat to your timeline. As a result of some of his experiments (I won't go into details here), the Chronopolis region (which was not there in the past) was sent to 12,000 B.C. So, that year, there was a temporal bifurcation between the timelines of the first and second game, and thus they differ from that point forward.

To left to right: Belthasar in Chrono Trigger; Belthasar in Chrono Cross; and Neo Epoch in Chrono Cross. Source: Nintendo Blast.

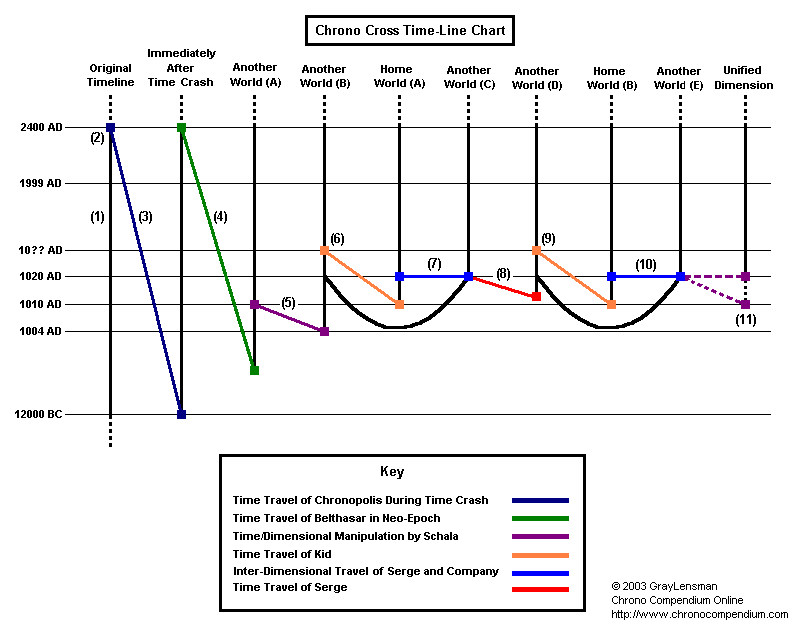

From 12,000 B.C. backwards, Trigger and Cross's timeline is the same, but from 12,000 B.C. forward, they change. But the interesting thing about this whole reel is that, I don't know if you've noticed, but unlike Serge's drowning case, this 12,000 B.C. fork was not caused by a divergence of possibilities in the past, but rather was caused by a consequence of the revised future of Trigger's timeline. Many more time travels will occur that will create other minor time modifications, as you can see in the image below.

One might think, “hmm, this is a case, then, of the Bootstrap Paradox.” So… Masato Kato solved this problem. A Bootstrap Paradox did not occur. Let me explain: what is the reasoning for thinking that it would be a paradox? Basically this: “where did Cross's multitemporal Lavos come from? From Trigger's non-dystopian future. But how did Trigger's non-dystopian future come about? After a victory against Lavos”. It turns out that the Lavos, who was defeated in Trigger, is not exactly "the same Lavos", but another temporal version of Lavos that has merged with a character from the series named Schalla.

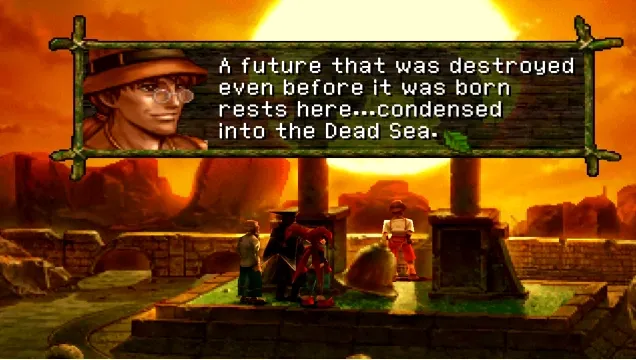

Belthasar sent the defeated Lavos to 12,000 B.C. in an unforeseen way (I won't go into details), generating a Time Crash, which is why there is that strange Dead Sea region in Chrono Cross (image below), and also a connection to the reptile timeline (where Lavos never existed). Thus, there has been a fork in the past in such a way as to result in this region having existed a long time before it was created in the Trigger timeline.

Notice, then, that in Trigger's timeline there was a Lavos in 12,000 B.C., but from the point of view of Cross's story, in 12,000 B.C., not only is there the Lavos of Trigger's timeline that would be defeated by Crono and his friends, but there is also another version of the defeated Lavos that remained existing in a multi-temporal context (outside that time), threatening other timelines (hence being called the Time Devourer). In terms of "being", it is the "same Lavos", but which, from a temporal point of view, "is more than one".

We will discuss more about this issue of identity and existence in time in the next article. Not just about Lavos, but about Serge as well. Who is Serge? Can we say that the two Serge from Another World and Home World are the same? Wait for the next article.

The end is just the beginning

In conclusion, I would just like to organize what we have learned in this text. We have learned that there are different incompatible conceptions of time. Time can be conceived as linear or non-linear, for example. And within the non-linear conception, totally parallel timelines can be conceived (without sharing a common past) or they can be conceived as branched times that share a common past and that create branches from “possible futures”.

The Dead Sea in Chrono Cross. Source: Nintendo Blast.

Finally, and most importantly, we learned that the ontological model we use to think about time directly affects the consequences of the concept of time travel. In linear time, time travel can generate several paradoxes, like the one in Bootstrap, which we talked about most, but also others, like the Grandfather Paradox. On the other hand, time ramified into possibilities does not suffer from this problem, because each thing that changed in the past generates a different future and the other future does not cease to exist but coexists, only in different branches. Finally, we saw that even in a branching time with a common past, it is possible, via time travel, to create a parallel timeline, with an alternate past (and not just an alternate future), which is what happened when sending a future region to 12,000 B.C. where it didn't exist.

What is the “correct” conception of time in the context of time travel? We do not know. There is a long discussion in Philosophy, aligned with debates in Logic and Physics, and here I have only touched on the subject superficially and directly in line with the Chrono series. But for an overview of these themes in Philosophy and Logic I recommend van Benthem's The Logic of Time, and Stanford entries Time and Temporal Parts. For more information on the Chrono series chronology, I also recommend the Chrono Compendium portal. We do not end here, as there will be a next article (Part 2) in which I will discuss identity and existence in these temporal contexts presented here.

This text was originally published in Nintendo Blast (Portuguese).