Final Fantasy XVI and the Sins of Individualism

Square Enix's latest opus doesn't have the emotional weight its story hopes to carry

There is a moment in Final Fantasy XVI I can't stop thinking about.

Near the end of the game, when Clive engages in the ultimate battle against Ultima, the game presents a rather well-worn RPG trope. The power of friendship, by design, is the rite of the protagonist to gain overwhelming abilities that push him beyond the limitations of the self. This concept has been used again in again in games such as Kingdom Hearts, Xenoblade, and Persona. It's a present Final Fantasy trope signifying the "anime-esque" beats that have riddled its identity.

Clive, toe-to-toe with Ultima, is physically but not spiritually alone. The voices of his comrades resonate with him during the fight's many phases, living and dead. This recourse is not simply the representation of Clive's powerful will: we are shown that Clive's abilities gain a significant edge over those of this deific being because of his emotional bonds.

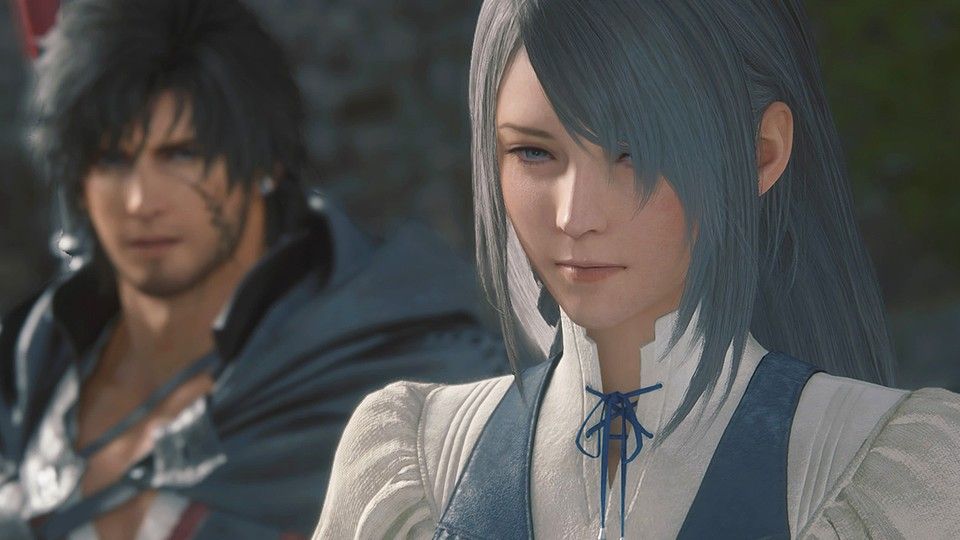

In most games, this moment would be significant. In most games, this moment would be visually represented by the presence of the actual characters who have stayed by the side of the protagonist through thick and thin. Final Fantasy XVI, by nature of its design, has no static party members. Clive, in this battle, is physically alone. He has succeeded the deaths of his brother Joshua, his comrade Dion, his mentor Cid, and countless others; he carries the willpower and perspective of his people, and he bears the love of Jill in his heart.

Unfortunately, it rings hollow. The moment should carry significant weight—instead, it is an awkward reminder that despite the game's aspirations, it is a slave to its own stubborn design.

Individualism as Superpower

In 1992, Detective Comics killed Superman. In a titanic and splashy clash, the titular character fought against the prehistoric alien Doomsday. Designed specifically to combat the invincible Clark Kent, this was a particularly powerful villain that could only be bested by Superman's terrific power, as is the case with the fictitious Übermensch.

Doomsday is not a particularly interesting villain. He has no central philosophy except that he wants to destroy everything around him. Doomsday is the personification of hatred and destruction, mirroring Superman's valor and salvation. Superman, by design, is the only person who can stop this terrible force. Their final fight is grandiose but empty of meaning—the pair stands in the downtown streets of Metropolis, exchanging mortal blows.

At the end of Final Fantasy XVI, Ultima is not defeated by some grand mechanical epiphany or eleventh-hour revelation. Ultima, a hive-mind of entities that once ruled all of Valishthea and hoped to do so again, is bested in single combat by the game's hero. Clive, who has faced down villains again and again, seems to only grow in power through his contests. While the Eikonic abilities he sources from his comrades and foes are of Ultima's design, he is able to turn the weapons around on Ultima.

Despite this power, the final shattering moment in the battle is not granted by a superweapon or a magic spell: Clive simply punches Ultima so hard that he dies. This moment, a showcase of human frailty overcoming deific invincibility, instead feels so divorced in tone that it might as well belong to a different game entirely.

Final Fantasy XVI's narrative construction is confusing, its underpinnings frustratingly animated by a string of readings in a compendium called the ATL. While the Active Time Lore system is touted as a way to remove needless exposition and streamline the game's storytelling, it adds little significance to what is essentially a tried and true Final Fantasy narrative. Clive amasses the power of the other Eikons, which is enough for him to defeat the very God that created them in the first place. He (Mythos) gains far more human power (Logos) and defeats the ultimate evil. Ultima Mythos. Final Fantasy.

The Crutch of Free Will

When properly delivered, the power of the human will to overcome existential evil can be very satisfying. Many RPGs retread the tried and true path, delivering stories about a small ragtag group colliding with an overwhelming force. The story of a disadvantaged group tackling corruption resonates with us because it fulfills a consistent fantasy. We are constantly surrounded by ludicrous and intense evil, and we must often look away from injustices in order to continue our daily lives.

Hero narratives have long endured their share of popularity. Joseph Campbell claimed that hero stories reveal deep psychological truths about society and that their timelessness hearkens back to our earliest storytelling. The monomyth, in part, reveals to us the desire of the ego to hold great power. While the not-so-secret desire to single-handedly change the world is countlessly reinforced in storytelling, it remains a fantasy that's ludicrously shallow compared to the very real power of collective action. The only true way to "save the world" is to dismantle the illusion of the self, and that includes its representation in our fiction.

While the monomyth continues to retain its popularity (see: Harry Potter or the Marvel Cinematic Universe Star Wars or really any wildly successful franchise), RPGs that solely focus on the deeds of their protagonists can miss the mark on what is actually required to build a revolution. Hollywood is obsessed with individualism as a selling point because it captures the Western ideal: autonomy, self-reliance, and freedom. Final Fantasy XVI, proudly displaying its Western influences, is crippled by its insistence on placing American idealism at the forefront of its identity. Final Fantasy XVI refuses to reckon with its disparate themes; the early chapters of dense political intrigue feel lightyears away from the climactic space battles featuring clashing kaiju and characters regaling empty platitudes about the importance of a tenebrous "free will." It is, sadly, not mature enough to wax philosophical on much of anything; Clive is the vastly more powerful emulation of Jon Snow but with the momentum of a bull in a china shop. Valisthea, thankfully, is so immune to its own political and hierarchical changes that the world remains relatively undeterred to the most grandiose shifts in power and place.

Fantasizing about saving the world with your own brand of power and perspective is certainly appealing to many of us, but it bears no weight on reality. Games like Final Fantasy XVI are certainly a far cry from "reality" as we know it, but their narratives and characters insist on representing real and believable points of view. Final Fantasy XVI grounds itself on its inspirations, such as Game of Thrones, in order to fashion a plot of political intrigue. But it misses the mark by asserting that anything of significance can be accomplished through sheer willpower alone.

Collectivism, Subjugation, and Birthright Supremacy

Throughout Final Fantasy XVI the player is bombarded with the philosophical binary of freedom versus slavery. Whether by the physical example of magical Bearers colonized by warring nations or the dichotomy of the Ultima collective versus the sprawling individualism of humanity, its discussions of free will die on implications. The biggest is that free will is something intrinsically known, and that the power of individual will is enough weaponry to take down any opposing force. Final Fantasy XVI's philosophical floor is the presentation of free will as a magical force, an inherent instrument wielded by humans, despite relegating its themes of slavery and social subjugation to secondary narrative status.

"Will [...]—a blind, deaf, and dumb force that rouses human beings to their detriment."

Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy Against The Human Race

The power of the human perspective has been forged, refined, and polished again and again within RPGs. One of my favorite quotes from Xenosaga is when Shion says "A single human thought can change the world." While Shion is simply vocalizing that any number of factors can result in any number of futures, thought alone is not enough. It requires collective action. "The power of friendship" is reinforced by the audience's metatextual belief in the strength of collectivism. While modern audiences might sneer at the trope, it feels so satisfactory time and again because it builds on a story's narrative beats and society's communal aspirations.

Clive's vicious back and forth with Ultima at the game's climactic encounter falls flat because any reference to the game's collectivist identity is mechanically unsound—it is simply the right of the main character to combat the main villain. Any narrative reasoning for why individual characters are not at Clive's side during this encounter (namely Jill) requires supremely hefty lifting. For instance, Final Fantasy XVI does a poor job displaying any (hard or soft) magical reasoning for why the distribution of the Eikon powers does or doesn't weaken its hosts—it makes little sense as to why Dion can do something that Jill cannot.

Perspective further deteriorates Clive's power outside the narrative reading of "Mythos" (The Chosen One). If the power of friendship has supreme metanarrative power, so does the power of the protagonist. Final Fantasy XVI bends over backward to deliver us the ultimate main character, the true entity upon which all power can be channeled for the greater good. In previous Final Fantasies, superhuman powers are meted out by the context of the story (except on rare occasions, such as the Final Fantasy XIII sequels or Advent Children) because it does a disservice to the unique necessity of individual party members. In titles such as Final Fantasy X or Final Fantasy XII, there are strong arguments that the protagonist exists solely for the player's benefit; Yuna is the actual focus of the story in X, Ashe in XII.

Jill's treatment in Final Fantasy XVI can be easily relegated to the kind of misogyny too often delivered by Japanese video games. In the Kingdom Hearts series, Kairi has often been hinted at as having the same sort of powers as Sora and Riku, but in the series' two decades of existence, she has not been granted a second of playability. For Jill, her lack of permanence feels even more hollow: by rights, she has as much reason to serve as Final Fantasy XVI's protagonist as Clive. She has endured equivalent suffering, faced equivalent hardship, and overcome equivalent hurdles. The worthiness of perspective, it seems, can be more readily delivered when your protagonist is tall, handsome, and masculine, with a head of foppish dark hair.

Here is where the problem of individualism in fantastical narratives truly resonates. We accept Clive's power because of his place on the box art, in advertisements, as the controllable protagonist. As with games such as The Last of Us, the lack of critical literary analysis among gamers (and audiences in general) means that there is a significant push in perspective weight provided by the protagonist. Main Character Syndrome, or the general solipsism of gamers, can be preyed upon by savvy developers to undermine the audience's expectations, but far too often it's simply the crutch necessary to make a character seem more interesting. I would be impressed by anyone's ability to argue that Clive has a more interesting personality or backstory than Jill, though Final Fantasy XVI is burdened with both a protagonist and deuteragonist lacking in charisma.

Unresolved Resolutions

In its early hours, Final Fantasy XVI sets itself up as a grandiose epic that is intensely political in scale. The game's early demo had many people excited over the prospect that Final Fantasy might be returning to the design of Matsuno's impressively dense games, such as Final Fantasy Tactics and Final Fantasy XII.

Final Fantasy XVI errs by demanding that we find our protagonist's plight entirely more compelling than any other character. In contrast, Final Fantasy XII presents a robust party with differing goals, pasts, and challenges, while XVI narrows the scope with its mechanical indifference to party makeup. Even when Cid joins us in the early hours, the game feels impregnably alone—our only comrade is a mentor device talking at us that cannot be meaningfully interacted with. Perhaps Final Fantasy XVI as a whole might have been more interesting should the protagonist himself be more interesting, but even in games where the hero is bristly (Final Fantasy VIII, .hack//G.U.) there is a company of secondary characters to balance that out. Final Fantasy XVI's narrative insistence on party instability (minus Torgal, of course) certainly lends itself to the Devil May Cry influences, however any writer worth their salt could find ample reason to keep Clive, Jill, and Cid together for the majority of the game.

Benedikta's death, early in the game, feels the most at odds with the narrative as a whole. While initially worrisome (Benedikta is one of the very few notable female characters in the entire game), Benedikta's death spells out something far more troubling: the erasure of an interesting character. Clive, alone, is not enough to drive continued interest in the goings-on of Valisthea. While Final Fantasy XVI has quite the array of characters, it essentially deletes them one by one in service of the greater agenda. Clive, Joshua, and Dion's assault on Ultima's flying island feels anemic compared to the operatic endings of past Final Fantasy titles. Whatever reason the ATL can summon for why Jill does not join is beside the point; Final Fantasy XVI could have succeeded in referencing the classic four-person "Warriors of Light" party to sew up the journey but it's more interested in its shoehorned resolutions than anything classical.

Without even examining the misogyny at play, we are forced to contend with the loss of Clive's necessary foil. Final Fantasy XVI seems to forget that the forging of personality does not come solely from one's foes—civil disagreements are a requirement for crafting a well-rounded perspective. One is tempted to imagine a plot wherein Benedikta's survival created a clashing environment aboard the second Hideaway that might have led to a more robust exploration of collectivism in the face of adversity. Instead, the deaths of Cid and Benedikta were used in the most contemptible way: emotional beats that advance Clive's personal journey.

Foiling the Audience

There is a point when an author must understand the dangers of genre subversion. Final Fantasy has poked fun at its own tropes and stereotypes many times before; Final Fantasy XVI's "The legacy of the crystals has shaped our history for long enough" doesn't read as a subversion, but a realignment. For much of Final Fantasy XVI's interview cycle, its developers and writers celebrated its differences, though one might point out how adjacent long-running series continue to build upon the groundwork of their predecessors. While Final Fantasy XVI worked so hard to differentiate itself, games like Persona 5 and Dragon Quest XI brought their systems, identities, and worlds into the mainstream video game era without sacrificing identity.

Final Fantasy as collectivism has existed in the core makeup of the series since its inception. Themes such as revolution and camaraderie are a through line of Final Fantasy, a backbone that unites the series' disparate identity beyond crystals, magic, and summons. While fans become lost in the weeds trying to tie down exactly what Final Fantasy is, we can at least unite in the fact that the series burns with the soul of revolution and change. Even Final Fantasy XVI places itself squarely in the narrative scope of fighting against oppression and overwhelming evil, even if its philosophies are misguided.

Revolution itself is not enough in the scope of Final Fantasy; its collectivist theme is shared by a group of young people setting out to change the world together. In Final Fantasy Tactics, Ramza Beoulve's perspective is granted importance because of how he aligns with the greater political and social movement overtaking Ivalice. Clive and Ramza share many similarities: they are both young disparaged royals seeking to right the wrongs of their nations. Ramza, however, is positioned as a receiver for the movement; most of the villains he faces bear indefatigable perspectives on class, society, and nationalism that profoundly affect the scope and trajectory of his journey.

In contrast, Clive's initial drive is adopted from Cid's and then changes very little all the way to the finale. He seeks to destroy the Mothercrystals as a point of salvation for the enslaved Bearer class, and it is awfully convenient that the main crux of the story requires this very same goal. Clive has no reason to ever develop any philosophical density but instead continues the work started by his father and Cid. There is no more reinforcing moment to Clive's lack of personal perspective than when he faces Barnabas' raging zealotry—in the face of lukewarm religious and existential diatribes, Clive is rendered mute, robbed of his own rebuttal of agency. As Thomas Ligotti says in The Conspiracy Against The Human Race, inspired by the insights of Schopenhauer, "Vandalism of the environment is but a sidebar to humanity's refusal to look in the jaws of existence." In order for Clive to fully contend with the failed merits of his "free will," he would have to acknowledge the path of destruction that brought him to his end goals.

This, again, is the problem of tacking on the totality of perspective to one person's enormously flawed sense of self and self-preservation. The issue with Main Character Syndrome is that none of us are inherently that interesting; the summation of our identities is the clash of exterior perspectives. Clive's mechanical and narrative solipsism is stubbornly driven towards an unchanging end goal: destroy the Mothercrystals, collect Eikons, and fight Ultima. Even against Ultima's banal and stoic desire to restore a misbegotten paradise, Clive cannot summon much in the way of reason aside from the shallow protection of "free will."

The contest of wills in Final Fantasy XVI comes down to this innate assumption that everyone deserves existence, even when the game forgets about the plight of its Bearers or the perspectives of its secondary characters unless they necessitate the plot. Clive quite literally robs people of their agency, affixing their powers to himself. When Joshua punches Clive in the face after he absorbs Jill's Eikonic power, we are treated to a rare and critical moment of self-awareness: Joshua is damning Clive for his incredibly narrow perspective. Final Fantasy XVI is intent on enforcing the singular importance of an individual no matter the cost.

Raison D'etre

At the heart of any story lies a single question: What is the point? Stories don't need a core morality to necessitate their existence, and plenty of stories live on vibes alone. But from an authorial perspective, there is a reason to write any story and a purpose that it serves. In Final Fantasy and other RPGs, the point is often some variation of a core theme: the destruction of evil, revolution against an empire, and the salvation of the world. But these are only the broad strokes of a tale and rarely do they encompass the whole meaning. While saving the world is honorable, it does not contain the intimacy required to resonate with an audience. Stakes are then built based on romantic, existential, and communal points to narrow the scope and force an audience to care.

Final Fantasy XVI is aggravated because of the misuse of its themes. Most players might recognize the concept of "Chekhov's Gun." Essentially, any seemingly unimportant (but intentionally referenced) element early in the story becomes significant later on in the plot. There are any number of ways in which the gun might go off, and Final Fantasy XVI at points is so at odds with itself that it seems as though it had forgotten to load a round.

There are any number of frustratingly unresolved elements in Final Fantasy XVI, and whether or not these become "answered" in future DLC does nothing to sate the inherent narrative flaw. Justifying the existence of DLC by withholding elements is a massive industry problem—no one should ever have to wait for the "complete" version of a game they paid over $70 for. Whether it's Leviathan or Metia or The Fallen or the very nature of Mythos and Logos, Final Fantasy XVI intentionally leaves information on the table that isn't satisfactorily accounted for in their database. While plenty of games leave open-ended mysteries to satiate a terminally online audience, Final Fantasy XVI's narrative does not present itself in such a way as to leave these breadcrumbs. Elden Ring's mysteries are interesting because of the game's unique dissemination of information—in the case of Final Fantasy XVI, these plot points just seem to be missing.

This matter of perspective feels punishing because of how Valisthea's massive world is shoehorned into forced answers. Final Fantasy XVI's ATL feels more of a narrative crutch than a database; similarly to Final Fantasy XVI's regressive use of a hub area, the ATL is a recourse by which the writers can fall back on half-cocked answers that might have been better delivered through exposition and cutscene. Again, Final Fantasy XVI's arrogance in subversion actually critically wounds the game. It doesn't seek to reinvent the wheel, but its version of genre "progress" is sated by temporary pomp.

Near the end of the game, Final Fantasy XVI seeks to enforce Clive's existential woes with scenes recalling characters from his past. There are a number of ways in which Final Fantasy XVI evokes Final Fantasy IX's more rounded philosophical beats. Ultima's tangents reflect Garland's in Pandamonium, and Zidane's famous "You Are Not Alone" segment mirrors Clive's internal dive into his temporary past. But where Final Fantasy IX lands, again, is in the unification of its mechanical and narrative storytelling beats: as Zidane limps from battle to battle, his comrades jump into the fray to help him ward off a violent death. Clive's comrades, in contrast, are neither capable nor present. Clive feels alone in every possible way.

The Lone Hero

You cannot save the world alone. Even within the grandiose spectacle of an RPG, believability doesn't end with dragons, magic, and absurd spectacle—any amount of gilding the lily can only embellish what works at the core of the experience. Final Fantasy XVI's narrative limitations are a yoke on Clive's back, not only from his mechanical inability to work with party members which results in drier gameplay, but because there are no visible bonds forged with its secondary members.

Individualism itself is often represented through action: the power of the sole character in film or television that can save the day, waging war as a one-man army. Traditionally, we are used to seeing collectivist ethos in JRPGs and individualist ethos in WRPGs, which of course is immediately framed by Final Fantasy XVI's supposed "European" medieval inspirations. The stories in JRPGs often feel richer because they are specifically enriched by their collectivist philosophies.

In Western RPGs we are used to the stoic protagonist via tabula rasa: player-driven choices stem from the immediate individualist identity born through character creators, moral choices immerse the player in a sense of "me versus the world" ethos, and responses are colored ambiguously to grant the player the illusion of choice. This, itself, seems to deny Final Fantasy XVI's insistence that the protection of free will is the ultimate goal of any sentient creature; Final Fantasy XVI, free of player-influenced choice in a linear story with but a single ending, can be replayed ad infinitum only to produce the same outcome. So much of Final Fantasy XVI seems purposefully disparate to Final Fantasy XIV, the team's other successful game, both narratively and mechanically that it feels pridefully purposeful.

The idea of free will is contested because of the central agency it provides humans. Free will is manifest because humans want to believe they are not baser creatures, that they can rise above the rank of animals and have some say in their lives and destinies. In JRPGs, gods and evil beings often deny the free will of humans because of their hierarchical rank; omniscient, all-powerful beings would have no desire for any individual human to meet them as equals. Ultima, then, collectively failed to create the human race and then denied them free will at all—it seems that in order for the Mythos project to be realized, Ultima's hand was forced to provide humanity with what it required to establish consciousness.

Free will in the case of Final Fantasy XVI can be simplified to pedigree. Clive, older brother of the one blessed with the Eikon of the Phoenix, born into a rich family, given combat and survival lessons at a young age, just so happens to be the entity that would become Mythos. While there is tragedy in his life, Clive's dogged pursuits are gilded by privilege. Although Clive comes to represent his fellow Bearers, the path that leads him to Ultima reeks of determinism. Collective action is rendered completely impossible by the nature of the game's narrative, as though hamstrung intentionally by the writers.

The point is indelicately hammered home: Clive, the individual, bests Ultima, the collective. As established with Superman and Doomsday, this does not come down to reason or philosophy, but simply that Clive is stronger. Mythos, as a concept, heralded possibility: anyone could have been Mythos. Logos, the blasphemed inversion of Mythos, is the emergent individual asserting his own will. It is only mildly ironic that in Greek, Logos was used as a word to represent the ineffable ability to reason. To take it a step further, the denial of Mythos and the acceptance of Logos is the rejection of fantasy and the acceptance of reality. It is the refusal of what is possible overwritten by what is. The individual, unsupported by the collective, cannot fathom the endless possibilities the future might hold. The individual is rigid and conforming whereas the collective branches toward the infinite.

Collectivism Framed Through The Individual

There are plenty of games that utilize the perspective of a single character to reinforce the structure of a collective society or otherwise unified aspiration. Death Stranding and The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom have inspired many with their depictions of post-apocalyptic restructuring. Death Stranding's abject loneliness is punctuated by collective action with other players that results in mechanical improvements to the overall game world. In Tears of the Kingdom, your major rewards are the spirits of comrades who fight alongside you, and the world itself is punctuated with moments where the direct results of your actions are the betterment of a fledgling society scarred by war.

The Final Fantasy series has long been criticized for its "linear" construction, though this argument is too often leveled against its physical world and not its plots. Final Fantasy XIII has been infamously criticized for its "hallway" area design and rapid-paced story that leaves little time for nuance. While Final Fantasy XVI goes out of its way to circumvent this by its cycle of story to hub area to quest chains, it inadvertently narrows itself similarly to Final Fantasy XIII by removing so much player agency. JRPGs, infamously, are mechanical in nature—the genre is often defined by obtuse stat-based systems and rewards that satisfy number-hungry players. Final Fantasy XVI limits this entirely in both its straightforward leveling system and thin weapon upgrade system. The thinning of these systems forces the player to focus on the remaining component: the plot.

While Death Stranding might present a wholly obtuse narrative and Tears of the Kingdom enforces details and vibes over narrative, players are rewarded when they are reminded that a video game's chief function is not to mimic other storytelling mediums but to strike out on their own. Final Fantasy, as a series, is insistent on cinematography, graphics, and spectacle. This is why, when the plot and characters fall flat, it is easy to recall a more golden era enriched by plot and character. While the producers are intent on providing players with an epic experience full of grandeur, it can often feel like a meal whose presentation belies lackluster ingredients.

Our Final Fantasy

Final Fantasy XVI was created by a particular team, led by a particular vision. When a new numbered Final Fantasy releases it's difficult not to summarize it as both an evolution and a metric—Final Fantasy XVI has been celebrated chiefly because of its scope and themes. But at the core of the experience, there are flaws within the very essence of the series; its iterations are antithetical to a more elevated storytelling.

"I think, for me, that Final Fantasy is all about making that cinematic experience. You think back all the way to the original Final Fantasy on the original Nintendo Entertainment System, you start out, you play the game a little bit, you get to a certain point, and then you finally get that opening scene. And that truly cinematic experience, it separates itself from other games and makes it like a movie."

Naoki Yoshida

"...when you play a Final Fantasy, you know it's a Final Fantasy."

Michael-Christopher Koji Fox

Final Fantasy is Moogles and magic. But that is only the aesthetic decoration: Final Fantasy is a collectivist mythology that celebrates revolution in the face of adversity. The promotion of individualist power over the collective might drive youthful fantasy but it has no staying power in the cultural zeitgeist. If there is a greater purpose, it's in the characters coming together in order to meaningfully oppose a divine injustice. Perhaps, after so many years and iterations, it's more important for Final Fantasy's identity to be cohesive—or at least narratively sound.

As the video game medium continues to evolve, and as storytelling continues to be enriched across genres, Final Fantasy can no longer rest upon its laurels.

"As I've grown older, I've found that I like my fantasy based more in reality," said Yoshida. Reality is subjective, and after playing Final Fantasy XVI, I questioned what reality the team perceived.