God of War, and Grief

An examination of the role of grief in the narratives of the two God of War games

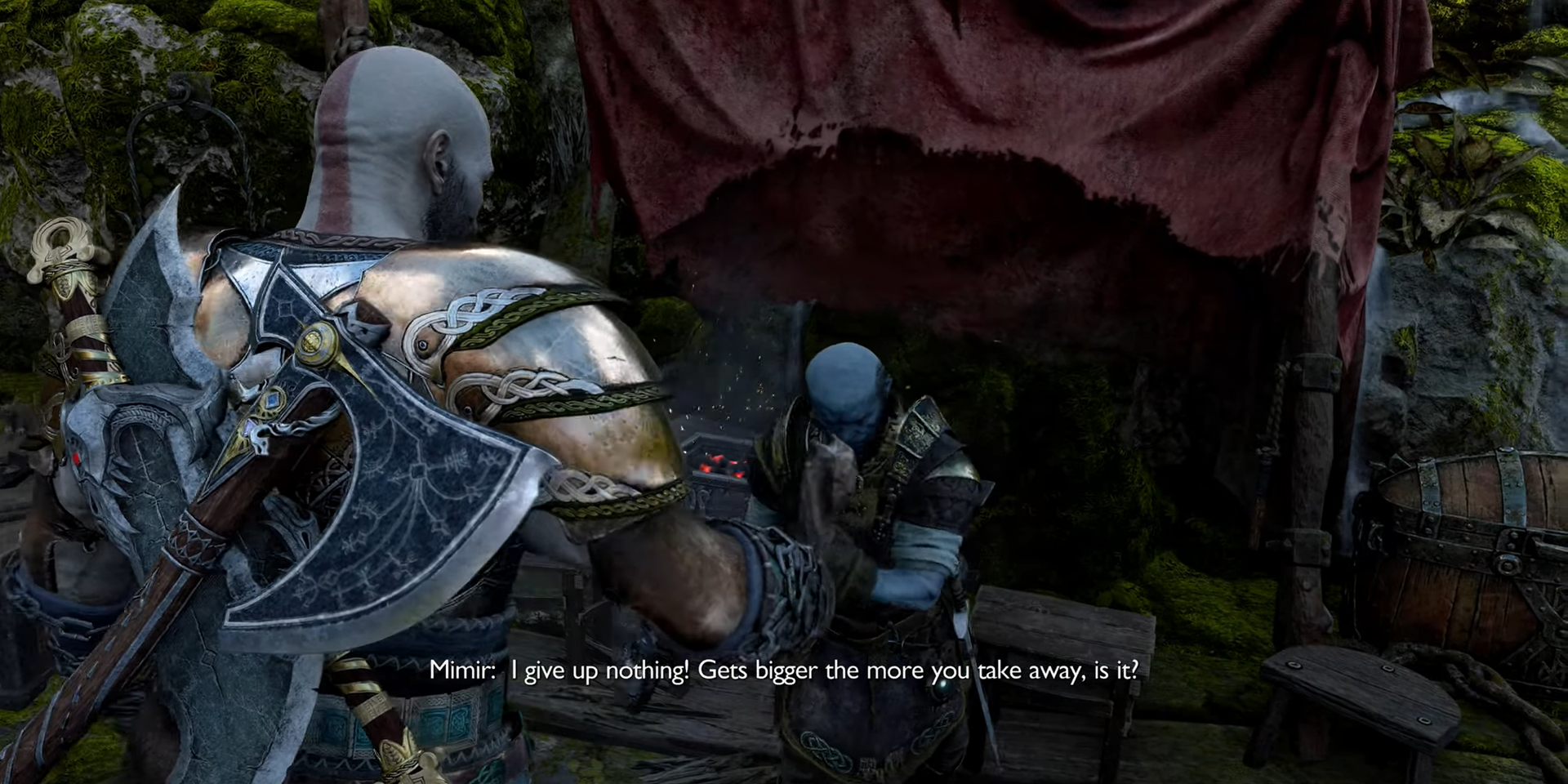

"What gets bigger, the more you take away?"

Grief comes in many forms. It's not something that can be fixed, or healed—grief is an emotion you learn to live with. It changes over time. At first, it comes in the form of anger, regret, and refusal. It transforms into mourning and melancholy. As it continues to mutate, grief becomes a thorn embedded in the flesh of your life, sparking pain only when you twist in that wrong way that forces you to remember it's still there.

God of War: Ragnarok, and its predecessor God of War (2018) build their entire narratives around grief. In God of War (2018), we visit Kratos as he is building a new life in a foreign land, his old home either abandoned or destroyed. The life he rebuilds is one of momentary solitude, the brief joys that visited him whisked away before the opening title sequence. It's not only his wife that he is grieving, but the personhood that he thought he abandoned. With his son, Atreus, Kratos is able to briefly redefine himself before the walls of his old life come crumbling down and he's forced to make amends with the old god of war.

God of War (2018) is not centralized by one man's grief, either. The war against the gods is one of attrition, and through protecting his son and making the journey to the tallest peak in the realms—a funeral request by his departed wife—Kratos must inadvertently wage war again. The violence that he succumbs to as his axe takes many lives, including the sons of Thor and the only son of Freya, his recent friend. Despite the cruelty and abhorrence of Balder, what we briefly see is a woman undone by grief both old and new, and Kratos' choices directly leading to a life of mourning.

God of War: Ragnarok picks up very quickly after the ending of the previous game, with Freya fresh in her malice and rage. The death of her son, while unavoidable, has changed the mother. She views Kratos and Atreus only as saboteurs, sources of her anguish. It's easier to fashion immediate anger on those who ended his life, despite the fact that many of Balder's sociopathic pains and tendencies existed long before their intercession. Freya cannot logically think her way through a situation that's colored by such pain, and the grief she bears is fresh in the hands of a god. Kratos and Atreus can only hide and bow out of the way because the other option is to bring violence to the doorstep of their beloved friend.

When it comes to grief, placing blame feels like the easiest balm. In our human lives, we do not often get the easy answers and resolutions that are present in fiction. We lose friends and family. We face tragedy. The suddenness of death and destruction is often so much that it drives the best of us to madness, and we must find some outlet or reasoning for the anguish that we feel.

Grief, then, changes depending on the person and the situation and is heavily influenced by circumstance. Even when we are at odds with a parent or sibling, their sudden death brings with it decades of complication. Upon death, a person can no longer defend themselves. There is no longer someone to bicker with or ignore. Humans complicate death because of its finality—even when we hate another person, we derive meaning from the possibility of a different future. Grief is only an after-effect, where its choices are made from the reaction, not the purpose.

There is some resolution with Freya, Kratos, and Atreus, and it is very complicated and personal. The Freya that changes does so because of Kratos' evolving selflessness, and the disparity between his living son and her dead one.

Parents—in most cases—will do anything for their children. A good parent is one that's willing to sacrifice, one that understands that the birth of their child colors their entire future. Children young and old need to feel supported by their parents because it gives reason and meaning to their lives. A child that has a strong parent behind them becomes a person that wants to live and succeed, and although every choice a child makes might not be completely on par with a parent's wishes, children need to face their own personal journeys and gain moments of self-reflection with a strong parent that is emblematic of their eternal home. Children want to know that they can go out and conquer the world and learn things and return to that same understanding they have always felt.

While Freya and Kratos go about rearing their children in many different ways, Freya's pain comes from the suddenness of the ending—she would have rather died than live in a world where her child is dead.

Kratos and Atreus, then, are given a new chance. Though there are growing pains with Atreus' teenage urges and questions, their ragtag group from the first game finds new reasons to fight in the second. Brok and Sindri, the loyal and inventive dwarves, continue to stabilize and equip the lives of Kratos and Atreus on their myriad adventures.

While Freya's journey becomes much more complex in the second game, her story often becomes secondary to what Kratos and Atreus experience, but this doesn't mean her grief is any lesser. Her grief for her son continues to color every single action she makes along the way. Even while Kratos is understanding, and Mimir reflective and jovial, Freya must face her open wounds and learn how to close them.

The grief that comes in God of War: Ragnarok is of a different kind.

Sequels often have a difficult agenda, and confuse themselves with their landing points. While Ragnarok does a fine enough job of tying things in a bow, there is one story that is given a deservedly more complex end. Early on in Ragnarok, there is a moment where Mimir is prattling on about his various humors and brings up riddles. Kratos (shockingly) has a distaste for riddles, but the other characters are happy enough to play along. After some are tossed around, Brok throws out one of his own: "What gets bigger the more you take away?"

Mimir, surprisingly, does not find the answer quickly. While Kratos shows that he is apt enough at solving them, he remains tight-lipped on the answer for Mimir's sake. The game continues and the riddle is mostly forgotten, another bit tangled in the yarn of Mimir's incessant prattling. Ragnarok becomes a game about answers, buoyed between Kratos' desire to take care of his son in Faye's absence and Atreus' drive to know more about the Loki he is supposed to become.

An unfortunate side-effect of Atreus' single-minded descent into prophecy and fate is that his friends are punished for it—Tyr, who is really Odin, finds an opportunity to release his frustration and kills Brok in full view of everyone before vanishing into the Realms Between. We are granted a piece of Brok's past before this, and it's suggested that he has died once before and that Sindri has done something to return him against his knowledge (and his wishes). This time, Brok's death is even more permanent—he cannot join the afterlife, and his body becomes only a husk.

Sindri is of course driven to madness over the grief of his brother's passing. Brok was more than a sibling and more than a business partner; Broke was Sindri's entire family. His death hits harder than most tertiary character deaths in fiction because of its suddenness. The betrayal comes along at a brisk pace, just when the game is winding toward its grand finale. Sindri, a jovial ally that's put Kratos and Atreus first time and again, is saddled with pain beyond any other. His entire world changes, his philosophies and perspectives marred by the fact that his eternal sibling is eternal no longer.

Atreus does his best to repair the relationship, but this is not a film or an episodic narrative. Sindri is not going to be mollified just in time for the big ending, and he's not accepting the secondary apologies granted by Kratos and Atreus in their after-the-fact fashion. The new Sindri, regardless of what happens to every other character in the denouement, must live forever without his brother. There is no happy ending for him, regardless of how Ragnarok happens or doesn't. Odin could live or die, Kratos and Atreus could live or die, the entire world could shift on its axis and it will do nothing to curb the rage and anguish that burns within Sindri's heart. This kind of sudden loss begets grief that eats you from within and colors the very reality at your feet. Nothing will ever be the same again.

While Sindri does show up just in time to put an end to Odin's fascist tyranny, he resists Atreus' half-hearted mollifications with a biting red-eyed backhand. While we have been trained since birth to offer apologies in all situations, we do not enough reinforce the notion that apologies can be resisted, and denied. Though heroic, Kratos and Atreus both faced an apocalypse with single-minded selfishness, and it was friends and acquaintances who paid the ultimate price.

Sindri: Oh, but some of us were bigger fools than others, aren't we? I gave you everything: my skills, my friendship, my home, my secrets, my treasures... and you just kept taking! And now what have I got? Not even my family. You want "sorry"? This is what sorry looks like.

Atreus: I— What can we do?

Sindri: We? There is no "we". There's only you. No matter what the cost. So what you can do... is get the FUCK out of my sight.

While Atreus serves as a poor Loki in terms of hundreds of years of reinforced mythology, he becomes a trickster god only in the department of those closest to him. Who he hurts is immaterial to the path toward fate and destiny. For those of us living small lives and struggling through our daily tasks, often as the background workers for our supposed betters, to be trampled underfoot after years of service feels uncommonly cruel. Sindri's grief is not even allowed to fester naturally—he must immediately enter service again, and become a tool of the force for "good." When Odin is finally slain and the protagonists waffle over the rights of his permanent death, Sindri does not waver. He takes Brok's hammer and smashes the oppressive god out of existence.

In a flashback, Kratos is given grief by definition by his dearly departed wife:

Faye: The culmination of love is grief. And yet we love despite the inevitable, we open our hearts to it. When the pyre is spent and you've gathered my ashes, spread them from the highest peak in all the realms. You will do this for me. To grieve deeply... is to have loved fully. Open your heart to the world as you have opened it to me, and you will find every reason to keep living in it.

While the gods in Norse mythology might be eternal, they are not immune to death and misfortune. It feels as though this might in fact be worse than being granted the injustice of an 80-year lifespan; it's impossible to know what grief looks like if you've lived with your friends and family for hundreds and thousands of years. And to many, the shape of grief is magnified by closeness. To lose a parent or a child can feel like a tragedy worse than any, but losing a sibling is often the thing that will tilt you over the brink of madness.

![Screenshot. [Character] Sindri stands over Brok's body, mourning.](https://www.superjumpmagazine.com/content/images/2022/12/Screenshot-2022-12-05-16.08.39.png)

After finishing the game, the player is presented with an ample post-game segment. There are quests to finish, bosses to conquer. There is also an optional (but entirely necessary) quest in this epilogue titled "A Viking Funeral." Upon returning to Svartalfheim, home of the dwarves, Kratos and Freya come across the meager party that is celebrating Brok's life with jibes and digs. While Brok's lifeless form lies on a nearby table, his remaining close friends can celebrate him by returning the same dour witticisms that were often sprinkled through Brok's particular verbiage.

His body is taken to the edge of a short at the bottom of a river, and it's here that a Viking funeral is performed. Before Freya can loose her arrow, Sindri appears with a lit torch. Sindri, wordlessly, places his hands on his brother's body. His armor is rusted, his eyes downcast. He says nothing. The love that passes is one borne upon lifetimes. He acquiesces to Kratos' help, and they push the boat into the water. After the flaming arrow lights the boat, Kratos places a hand on Sindri's shoulder. Sindri reacts with wordless accusation—there are some things that cannot be mended.

Before Kratos' attempt at condolences can be finished, Sindri vanishes. Mimir speaks.

Mimir: "A hole."

Kratos: "What?"

Mimir: "Gets bigger, the more you take away."