On Borrowed Games and Save File Ethics

There was an age when you could rent a stranger’s time; here’s how I handled those borrowed moments

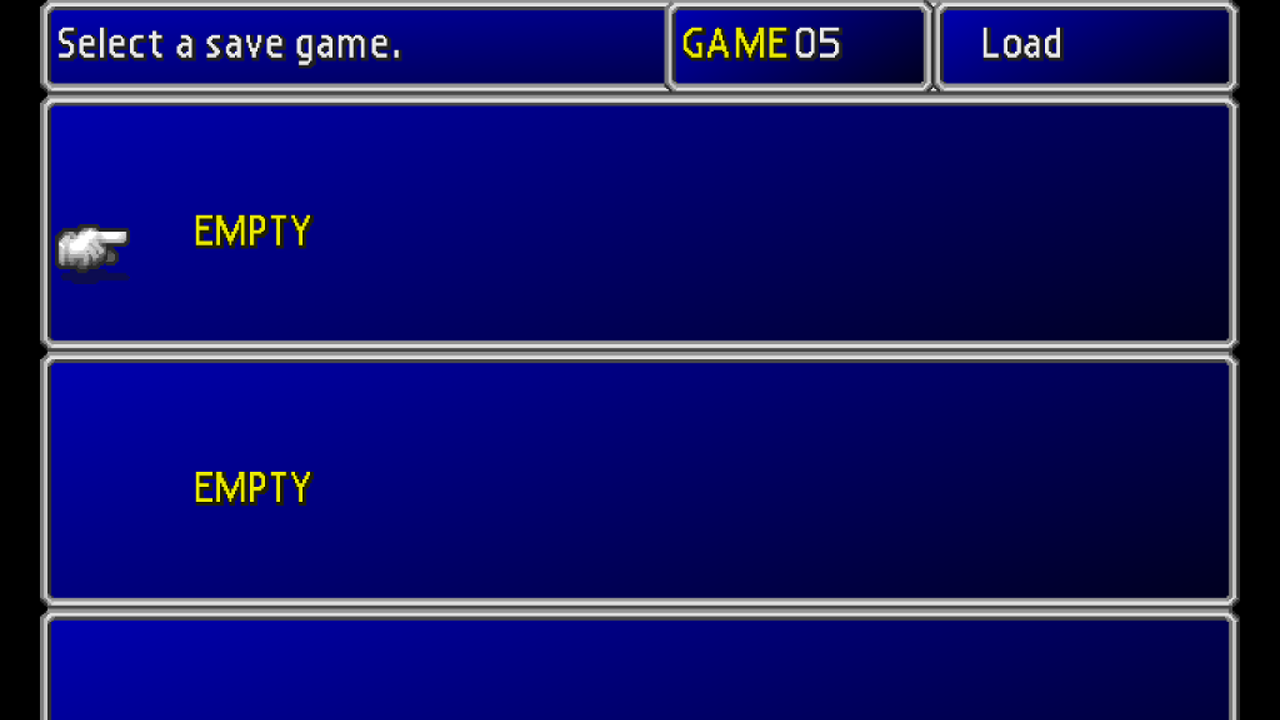

Retro game purists, those dedicated types who insist on playing their favorite classic titles only on true hardware, will often find themselves in possession of something unique when they purchase a game: an old cartridge. This may come with old save files, the last record of its owner’s playtime some decades past. It’s a moment in time frozen in the battery back-up, a few hours of someone’s misspent childhood. Buy the cartridge, buy the saves locked within. It’s now yours to use or delete as you see fit.

What is to be done with these possessed cartridges? What do you do with the borrowed saves?

The high era of the movie and game rental market overlapped with the era of battery backup. This created an interesting situation for the renter.

When one checked out a title, he might have also found himself in possession of a fragment of someone else’s free time in the form of an anonymous save file. This might represent minutes, hours, or days of that stranger’s effort, played across a single session or over weeks. But for the duration of the rental, the renter holds absolute control over this fragment of time knowing that someday, maybe soon, another person would control their time.

There was a subtle tension here, a pressure to finish each game in one rental period or risk being sent back to square one.

As a child, I had an obsession of sorts with save files, if only from a practical standpoint.

I was more a renter than a buyer. Specifically, a renter of RPGs and other games that I wouldn’t be able to finish in one weekend. I was worried that if I didn’t get to the store fast enough the following Friday, some stranger might beat me to the punch and erase my effort. In the same vein, I was concerned that I might carelessly do the same to someone else.

This led me to create two sets of rules: (1) an ethical code for handling the data of others and (2) a practical guide for safeguarding my own.

In retrospect, I might have taken this too seriously. Of course, it’s easy to think that now, in a time when the only real threat to a save file is yourself.

It’s only now — many years later, long after the evolution of the industry has rendered these rule sets moot — that I realize how this entire setup was strange.

There we were, a large group of strangers mediated by a business, blindly exchanging data, representing a significant portion of our free time without ever giving it a second thought. There was a time when, out of necessity, I trusted people I never met more than some of my closest friends. Somehow it (usually) worked out.

Finding a save file in an old game is a bit like finding a postcard in an old book. You can learn something about the previous owner, but only a little — only what they wanted to make known. I must infer the rest.

A save game could be a treasure trove of information. All it took was an eye for detail. Those RPGs that captured me back in the day? Everything about the file — the characters, location, stats — gave a peek into what was to come.

If the game tracked playtime, then this could give important hints as to the length of the game and the rhythm of its story. With a bit of deduction, the save files collectively could give even more information. Did many people reach the same point? Perhaps that’s where the difficulty spikes. Is there one file with hundreds of hours of playtime, while the others have very little? Either the title is heavy in bonus content, or (if it’s an older cartridge) you’re looking at a communal file, enjoyed by many over the years.

There is a story behind these files.

Those communal files were especially interesting, pointing to one thing that people love to do with other people’s saves: play them. That’s fine if one owns the game, but what if possession is temporary? There’s no quandary about using a password someone else earned — it doesn’t affect them. While it’s not as bad as deleting the file, doesn’t it still ruin the experience for someone if a stranger already kicked off several story events?

Playing someone else’s game was one item on my list of ethical rules. I reasoned it might be okay to play that file if it’s ancient and I could reasonably guess that the person who created it wasn’t coming back, but that wasn’t always clear. So what to do? I decided it was fine to play that file — just to get a glimpse of someone else’s experiences — but not to save it, unless there is an open slot into which I could copy the file.

I was probably the only person batty enough to bother codifying rules like this. Yet there must have been rules — unspoken rules between strangers that all of us understood implicitly, even if none of us explicitly agreed to them. How else can I explain how I finished so many of these games, or how rarely my own saves were ruined?

Throughout this piece, I’ve been using the word “strangers” to describe those who’ve been renting games alongside me. That’s would be a fair term if it was a game purchased from a secondhand store or a rental in a city, where there is a level of anonymity. In my case, “strangers” might not be an accurate word to be using.

I come from a small town in western Kansas, a burg that never exceeded 7,000 people. Entertainment options were few, as were places to rent movies and games. In a lifetime, each cartridge in its small collections would pass through many hands. However, it’s more than possible that I knew of the people who were renting these games and making these save files. I may have met them or spoken with them, or at the very least pass by them somewhere down the line.

Did I have some sort of relationship with these other renters? We led different lives, with nothing in common except ownership of a SNES and a taste for the games that one didn’t finish in a single weekend.

Still, those save files we exchanged represented a connection of sorts. Without being able to pick any of them out of a crowd, I was competing with them, sharing experiences with them, putting trust in them, and taking their trust in turn.

Maybe they were leaving clues in their saves, little hints — deliberate or unconscious — in the names of characters and files. Plenty of them lent their own names to the protagonists of these games, branding others with the names of friends or someone they were interested in. Or maybe they used an inside joke as a name, an obscure pop culture reference, or even some nickname that they used habitually.

Once you’ve seen the same name appear across a half-dozen games, you can glean some information about the person behind it, even if it’s nothing more profound than their taste in electronic entertainment.

This kind of sleuthing was something I never was interested in. Oh, if there was an in-joke I shared with a friend, such as a name I knew he always used, then I could tell what he’d been doing on the previous weekend, but that was it. My concern was strictly practical.

For all the nosing around I did as a kid, and for all the effort I put into preserving the data of others, I never cared all that much about the creators of that data. Even then, it never occurred to me that this was my community — or at least people I should know.

I used these rules for years, yet never wrote them down in any form. Yet even as the years rolled on, as the rise of optical media and external memory storage made those rules obsolete, I still remembered them. If I woke up tomorrow in the year 1994, I would know exactly how to handle that new copy of Final Fantasy III I’ve been so desperate to get my hands on.

The rules were very intuitive. They must have been if so many people could follow them without knowing of them.

How do you handle another person’s save files? Never delete one unless you must, and then only delete the one that has the least progress. Don’t touch another person’s file unless you’re absolutely positive that they’re finished. It’s common sense, or perhaps common decency.

As to protecting oneself against less decent people: Save your own files into multiple slots before returning the game, then delete the unneeded ones when you’re totally finished. Avoid saving in the first slot if possible — some people automatically delete that one without thinking.

It’s a minor miracle that this arrangement worked as well as it did. After all, none of these people really knew they were dealing with me — likely not even giving the person on the other end of that save a second thought. They were taking possession of something that was not their property — already a license to mistreat it, for many people — and then further gaining command over an intangible asset within that borrowed property.

How did I not consistently lose more progress? Are informal rules really this effective, or was I simply lucky all those years?

But I can remember one time when my saves were wiped out, losing weeks of progress. There was one big difference: I knew who did it.

I loaned a copy of Banjo-Kazooie to a friend so that one of his younger relatives could play it. This cartridge has a save at 100% completion, sitting in the first slot with the other slots empty. Yes, this was a breach of my own rules, but this was my property, not a rental — and isn’t the point of buying the game is so you don’t need to worry about things like this?

When the cartridge was returned, I discovered that whoever had played it had ignored those empty files and overwritten the first one — the one I’d worked so hard on. I was, of course, furious that someone had carelessly eradicated weeks of my time and effort. However, as aggravating as losing the save file was, the greater wound was that someone I knew deleted it.

Over the years, I’d entrusted hundreds, if not thousands, of hours of my time to the nameless masses and they treated it with care. It was a person I knew who threw that away.

Maybe there isn’t any deep lesson about human nature to be learned here, but I have a message for those of you who are building that cartridge collection.

When you find old saves, know that you may do whatever you want with them — but first, take a second to respect them, to respect what they represented for the people who created them. It’s not just data, it’s someone else’s precious time, and you should treat it as such, if only for a moment.

If there is one nugget of wisdom I can leave everyone with, it’s this: always make copies.