On Critique and Caring

Exploring the nature of critique

I was looking forward to Final Fantasy XVI. Even before the second trailer hit or a single minute of gameplay unfolded, I knew that this game was meant for me. Call it brand loyalty (it is), but I had faith in Creative Business Unit 3, the division of Square Enix also responsible for Final Fantasy XIV. I knew I would love what came before in the series; I understood the beats, tropes, and style. My bar for expectations was fine-tuned to the brand’s.

Then the first reviews came in and they were... not negative, but more critical than I’d expected. X-formerly-known-as-Twitter was quick to the attack and defense. My feed became a volley of opinions from those who had and hadn’t played the game — journalists, influencers, fans, haters, trolls, bystanders, developers — instigating a discussion that felt three parts genuine and two parts virulent. This was riding off the high of a relatively well-received demo, and the newly fluctuating sense of concern soured my excitement.

Aggregate reviews ended up pretty positive. It’s currently sitting at an 87 on Metacritic — which tends to be a “buy-me” score when I’m on the fence with a game — but there was so much “not quite” associated with FFXVI after embargo broke I felt myself growing resentful of all the nitpicking. Partly driven by the financials supporting the game’s marketing efforts and the ongoing struggle for its series survival, the success of the game was framed as a pivotal make-or-break situation.

While it’s true that people rarely play games based solely on numerical scores and nodding heads, many of us are achingly online — steered often by public, professional, and commercial opinion. We are often bombarded with scores in shades of green, red, or yellow. Shopping for games is not the old-school browsing of a Blockbuster. It is a curated series of suggestions, warning consumers what they may and may not like and not, necessarily, telling them what the game meant.

The art of critique is becoming a genuinely free enterprise — a proletariat utility, where anyone with an education in or a passion for something can contribute to the discussion on an influential level. Gaming is an expansive, largely digital, corporate-infused industry; a medium often so obsessed with the idea of being a valuable commodity that it’s becoming increasingly easy to commercialize, raising questions about the prevalence and necessity of the art. We’re crowding the field. So where do we source our experts? Should there even be any?

Really, what are we talking about when we talk about critiquing games?

What we talk about when we talk about critique

"The law is reason free from passion" is a quote from Legally Blonde. Well, technically it's Aristotle, but I'll always associate it with Legally Blonde, because, c'mon, it's Legally Blonde. A feminist rom-com American masterpiece. The "reason free from passion" stuck with me, because when I took environmental law in college, I would hear about CERCLA and the necessity of its implementation and think: that's passionate environmentalism at work to create the reasoning.

Nothing is free from passion, and this is true of even the most academic and scientific studies produced through evidentiary support. They are most often products of passion. Critique is much the same, although we often position it as an authoritative stance (through persuasive writing, which we spend a lot of high school and college doing) not necessarily free from passion, but in solidarity with reason established in study. We argue our point. These are the facts — objective, subjective, interpretive, historical — and this is my case. Critique is purported law; creation is unfettered chaos.

...you must know why you like a film, and he [sic] able to explain why, so that others can learn from an opinion not their own. It is not important to be "right" or "wrong." It is important to know why you hold an opinion, understand how it emerged from the universe of all your opinions, and help others to form their own opinions. There is no correct answer. There is simply the correct process.

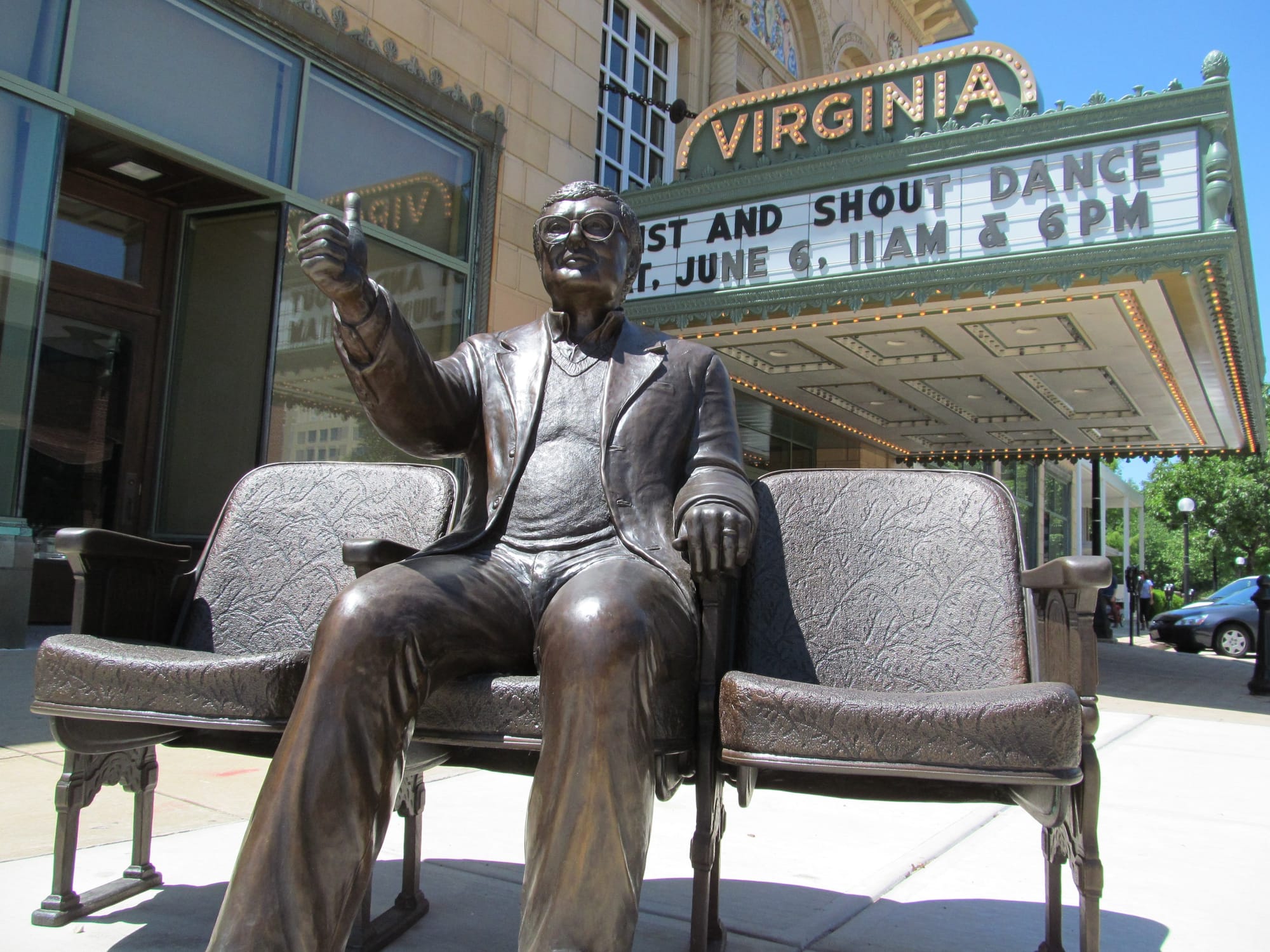

"Critic" is a four letter word by Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert, perhaps the premiere American movie critic, said that to critique is to uplift the new — that is the role of a critic. To “defend it, publicize it, encourage it. Those are worth doing.” The additional part is important. It designates innovation as a leading basis of critique, in finding novel ways of exploring various perspectives.

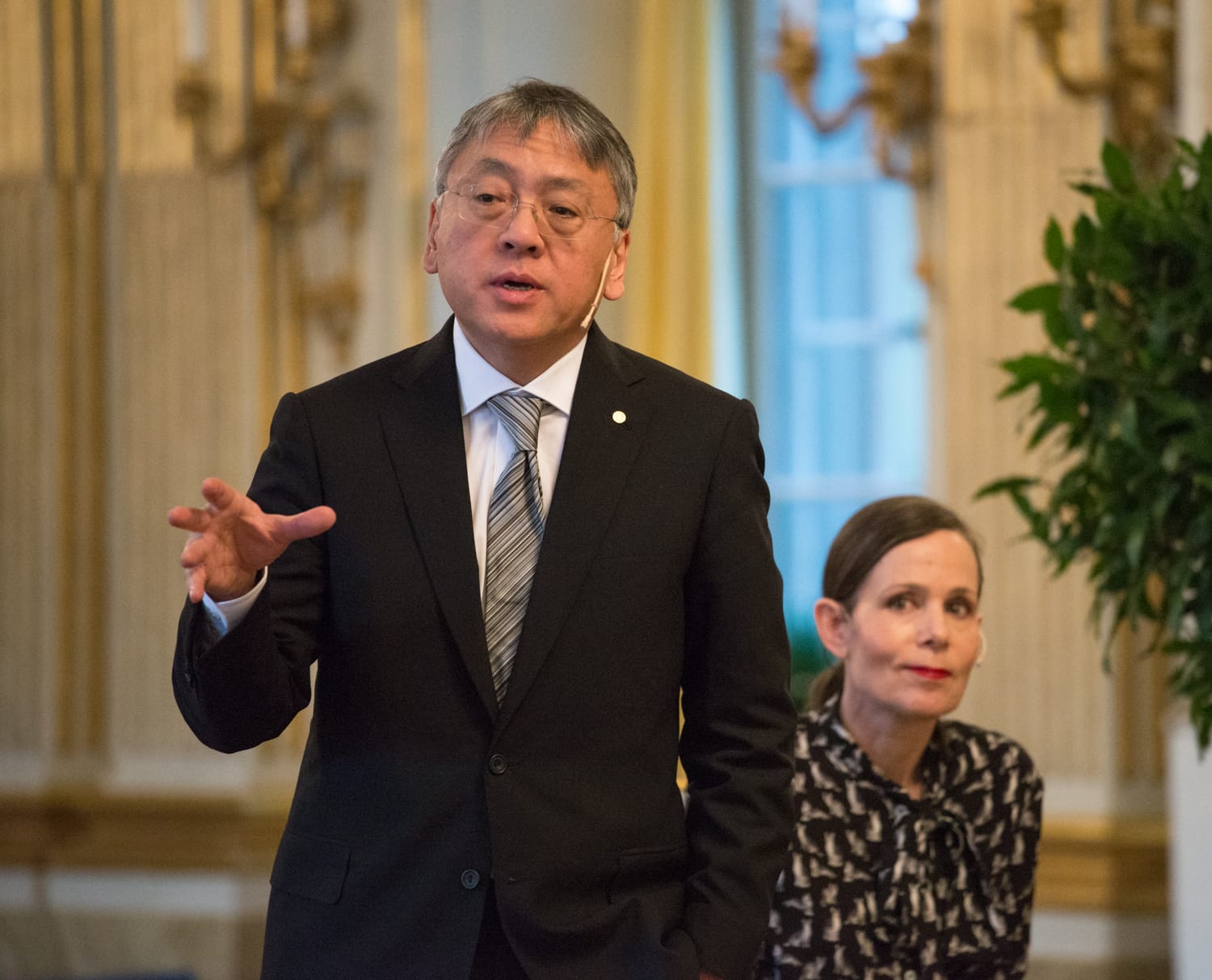

We’ve all seen romance movies, but have we all seen the terminal stillness of a life lived in service only to others, of the slow leeching of autonomy to class-based greed, of a too-late love destined for a quiet, imperceptible acquiescence to death? If you have, you’ve read (or seen the movie adaptation of) Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro.

It is a masterwork of a book, and with an adaptation that’s deftly done (Andrew Garfield captures particularly well — as he always seems to — a dull sort of joyful naivety, purposefully livestock-like in ignorance). There are other romantic tragedies out there, and there will be more in the future. It simply does the story well, critically and commercially. When we approach it from a literary perspective, we have the task of critiquing it. How do its narrative, character work, and imagery discuss the themes of love and human identity, and how can we apply them to, or at least identify them, in scientific and humanist conversations? Is this sort of reading essential to enjoying the material, or is it a superficial flouting of the navel-gazing few?

When I read through more negative reviews of FFXVI, my gut reaction was to scoff and shake my head in disparagement. I’d heard enough about its story (bad), its gameplay (fun), its world design (nothing special), that when I finally played the game, I wasn’t able to separate my bias from the hot takes I’d seen on Twitter. Polygon’s review was one coal I let sit in that fire, and the comments section on that got so spicy, they had to highlight the community guidelines and subsequently closed it. This is no fault of the author. They just had an opinion. The issue is that everyone else did too.

My major disagreements stemmed from the comments on Clive’s ignorance of slavery (he...was one), but that discussion isn’t really mine, so I pivoted to ground I could cover: the game’s approach to female characters. It was a similar criticism that I was, back in the day, astounded to see levelled at Final Fantasy XV — a game about four dudes — that is extremely popular with women, because it felt a disingenuous barb rather than reflective of the game itself. But the Kotaku article linked above about Jill, by Ashley Bardhan, stuck with me. While I didn’t agree with it initially, I shifted my bias to understand the writer’s ideas and sympathize with them enough that it tweaked my opinion and allowed me a more level-headed analysis of the game. It helped me see something I didn’t at first. That is the heart of critique.

There are often two cited approaches to critiquing games: those that use narrative (narratology) and those that use gameplay (ludology). But these are “camps”, so to speak, and they prioritize two different but interwoven things. A narrative lens echoes the same analysis standards of books, movies, songs, etc. How strongly presented are the themes? How creative is the approach? Is it a well-thought-out story? Ludology is more interested in the how — how the game is crafted, what techniques are used to immerse players, the technical execution of the gameplay and the presentation. They’re not mutually exclusive things, but people sometimes weigh differently one from the other.

Rarely does media have such a dual purpose: literature has its canon, as does theater and music, etc. Their stories are already dispersed through the cultural diaspora, implemented and known in public discourse in a sort of referential exploration that understands the presumed hierarchy of aesthetic. Games as competition (Esports, namely) are rooted more in the sports fandom, in pride in identity, competition, locality, and the art of physical skill (among other things; I’m not really well-versed in sports). Gaming is both a byproduct and a progenitor of these ideas.

Should games writing be subjective and experiential? Yes. Should it be based on a [sic] objective, analytical and based on a sound understanding of a century of critical theory? Yes. Should it be voyeuristic like good sports writing? Yes. Can you ever write meaningfully about a game you haven't played or finished? Yes. The biggest thing wrong with game writing at the moment is how polarised the ecology is.

You Played That? Game Studies Meets Game Criticism

The most difficult aspect of reviewing games objectively, for me, is in my lack of experience developing them and, often, my lack of expertise playing them. I rely on developers and other experts to highlight impressive graphical feats and combat scenarios, music use, and character design. I can appreciate those. Narrative critique, for me, is a different thing entirely.

I am extremely judicial in my appraisal of novels because I write them, but I also tend to be extremely forgiving...because I write them. I get it. I get the inconsistencies, the rushed resolutions, the slapping-a-hand-to-your-forehead-for-missing-a-tiny-continuity-error. And yet I wrote a nearly two-page rant a few years ago about a book I hated. And then I deleted the rant, because I felt bad, because the author had worked hard on this book. I admired them, and everyone else seemed to really like it. It’s one thing to sneer on my own, it’s another to stare at a creative next to me and say, “What you’ve made is shit” when the underlying implication is..."and I can do it better."

Less secure in their cultural position than their European colleagues, Paris-trained American composers such as Copland and Virgil Thomson may have felt threatened when Gershwin’s concert works were taken seriously by critics while theirs were treated as monstrosities. They relegated Gershwin to a lesser realm, even though his works often shared programs with theirs. Thomson admitted the success of Rhapsody in Blue, but noted that “rhapsodies … are not a very difficult formula, if one can think up enough tunes.”

Misunderstanding Gershwin by David Schiff

The issue with pulling punches is it’s also not fair. If you know when it’s done poorly, you also know when it’s done well, and most art contains parts great and not-so-great. However, there’s some growing sentiment in the art community that says just putting something out there deserves accolades. Sure, downvoting indie games isn’t the same as shaking our fists at AAA studios, but critique is a conversation that, when done thoughtfully, can help creatives improve and learn, even when it’s searing. When you critique as a creative, you have to know the same will happen to you. It’s part of being in the ring. We gotta buck up.

Art is not inherently competitive. It has always been a thing for everyone, but certain kinds of intellectualism posit that it is–that there is a war raging in the foothills of popular recognition, and we’d do well to fight it. “Poptimism”, attributed to Kelefa Sanneh in their New York Times essay “The Rap Against Rocksim“ (paywall), makes a stand for the merits of everything, even if they’re not “traditionally” executed. This isn’t merit by existence, but a broadening of approach: instead of selectively choosing proponents of a genre to be gatekept within the gilded walls of acclaim by “industry” opinion, we demolish the gates entirely.

Raising the brow

The question of other people’s subjective values isn’t a distraction from the question of quality. The question of quality requires that you incorporate, at some level, other people. It has to start with the question: “better” for what and for whom?

The ‘Quasi-Theological’ Turn in Art Criticism Is a Mirage Leading Us the Wrong Way by Ben Davis

The annual Game Awards is a show that frames itself as an “Oscars” of gaming, but the true draw is in the presentations, trailers, and world premieres. It is, at best, a celebration of gaming. It is, at worst, an advertisement for the machine. When we talk about “good” games, the real GOATs, we collectivize it as an audience. The Zeldas, the Mario 64s, the Resident Evil 4s. There is little “expert” input in the designation, so the Game Awards, in a way, feel somewhat superfluous. After all, who do we source as experts? The Game Awards 100+ panel of judges includes media outlets from across the globe, but doesn’t specify who, exactly, takes part in the screening. BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) has its own iteration of the gaming awards, a distinguisher because it boasts judges that belong to “a range of developers and publishers” which is also vague, but at least points to industry experience.

Speculative fiction’s premiere awards, the Hugo Awards, also hosts a category dedicated to the best game. This isn’t as in-depth for the medium compared to BAFTA and the Game Awards (which include awards for technical presentation, art direction, narrative, etc.), but it shows the seriousness with which traditional outlets of critical evaluation include gaming. But even the Hugos are under fire for a recent exclusivity fiasco, questioning the entire methodology of the judges, and the fairness of the current system. BAFTA’s 2022 game selections mirror those of the Game Awards, with Elden Ring, God of War: Ragnarök, and Final Fantasy XIV winning pretty much their equivalent categories for each. It is worth noting that these were not "niche" games, but rather some of the most popular games of the year. It’s rare in gaming that critics and audiences don’t agree on at least the general idea of what a good game is.

Metacritic tells a very similar story with audience and critic consensus for games. Often they match. Rotten Tomatoes is notorious for having the opposite problem, for a variety of reasons, but in gaming, the confluence of art and consumerism is fairly egalitarian. Perhaps gaming isn’t old or indie enough yet to have the same level of darling-isms that movies, books, music, and art do. Maybe it’s the open relationship with consumers that circumvents the entire problem. Maybe I just don’t see it.

But games have to be, above all, fun.

The closest gaming really got to a publicly noted distinction of the “highbrow” was in the Last of Us and its adapted HBO series, which elevated a gaming IP to artful television. But HBO’s Last of Us show is a show, not a game. The IP has become so internally self-aggrandized that it skirts greatness by sheer insistence on cultural canonization, although that’s not really my business. But all that proved was the story — not the game — was worth ascending to the greater American consciousness.

Critique is often groaning under the weight of this old hierarchy. Critics in the arts are not often celebrated, and opinions from the traditional high caste of taste are increasingly perceived as antagonistic to the audience. Furthermore, the curation of fan works and interpretations plays a role in immortalizing a work. The “razing of the gates” in the arts during the internet age left it open for a proliferation of opinions, and people from either side are scrutinizing the effects.

Cultural commentators are and have been exploring the ramifications of this for some time. Because we don't always trust critics, who can be seen as inaccessible, the American consciousness is finding it harder to give critique a foothold. We’ve simply boiled too much down to 180 characters. We don’t like to read long-winded opinions anymore. We’ve commercialized inner reflection hoping to turn the current pop culture landscape to glass, making it so saccharine, so uniform, that it deters people from engaging in the hard work of analysis. Detractors can be lumped in with those who have superficial complaints in order to discredit them or paint them as overly vicious snobs. There’s very little middle ground. And people who occupy it often have to lean one way or the other.

People are so threatened by the existence of disagreement, or even just of abstinence. In this new pop culture landscape, to merely opt out of these massive events is considered snobbish and uppity. You see a million viral tweets that scream “No one cares that you don’t watch Game of Thrones! Let people enjoy things!” as if it’s somehow hurting your enjoyment that other people choose not to engage. Non-participation is considered at best a social faux pas and at worst a sneering act of malice. It’s insane.

On Letting People Enjoy Things by Esther Rosenfield

This kind of comparative bafflement has always existed. The "we have x at home / x at home" meme. The eradication of intellectualism is taking place on the pedestal of popular opinion, as if all educated perspectives are somehow vastly out of touch, a narrative that feels pulled from a dystopian handbook. Gaming's relative newness means that conversation is really prescient. I believe we should have robust critique, that we can all be commentators. We just have to know what we're doing.

Source: YouTube.

Diversity in opinion is a good thing. Let people dislike things. I hope people dislike my things. I've been thinking about this recently with Forspoken, but on the opposite. Man, that game was recently $10.00 on the PS Store. I missed the sale but planned on getting it. It looks good! It always looked good, even when I saw the smash-hit compilation of its maligned dialogue. It currently holds a 64 on Metacritic. That's...basically 3 stars.

So why does it feel like everyone absolutely hated it?

The default of public opinion

When I first started working as a critic, I liked to joke that I had two different scales by which to judge movies, “Art” and “Pieces Of Shit.” And something could be a great Piece Of Shit—speaking of The Rock—even as it’s a poor claimant to the status of Art. It was intended as a jokey caricature of how to evaluate cinema, but the point is actually sincere.

Martin Scorsese’s infinity war by Alex McLevy

When Twilight (the book) released back in 2005, I was the prime target: 14 and already deeply drawn to winter-shrouded narratives. That series was my perfect storm. The books were romantic (I was 14), melodramatic (I was 14), and fantastical (and even if I wasn't 14 – it's not anyone's business). They were beloved enough that I could converse with my friends about them without feeling like I did when I was pulling out my old Digimon figurines at the lunch table to a very glazed-eye audience who'd long since outgrown them.

Famed film critic Roger Ebert gave Twilight's movie iteration (2008) 3 1/2 stars which is, admittedly, higher than I thought it would be. While he did not especially enjoy the movie, there were moments where it seemed he found reason to provide a broader appreciation of its approach: certainly, he says, there are movies that do this whole shtick better, but it clearly has merit.

The review was fair — he was critical, and it was direct, but it was done with a cutting, insightful humor and was, above all, appreciative of the fact that people flocked to this movie. Like, flocked. There’s an artful approach to the dislike that doesn’t feel like a visceral “punching down” of the film. He seemed to be in complete understanding that he wasn’t going into the theater to see the modern Wuthering Heights, despite what the movie’s emotional sincerity and allusions might show. Ebert’s review reflects that broader insight into the popular zeitgeist. This movie wasn't necessarily for him, but it didn't have to be: he accepted it as it was presented, with all its warts, reputation, and all.

He criticized the proceeding movies for their less than stellar critical reception ("...their charisma is by Madame Tussaud"), which, I personally think, can be attributed to a variety of factors regarding the franchise's consummation with capitalism, but it was already assured that the Twilight series would be a hit. Demand dictated the progression of the franchise from indie film to blockbuster production. Hunger Games would follow it. Divergent would follow that. And so on and so on until it becomes hard to push Twilight off the literary cliff and claim it as a moment of madness in the arts. It had ramifications. And this made a lot of people very upset.

For all its flaws, its tropes, its misrepresentations of indigenous cultures, its creepy romantic entanglements — Twilight endured. Grappling with a complicated media legacy is nothing new, and there have been exhaustive essays on Twilight’s sins, its merits, and everything in between. Many were insightful and educational, especially speaking on the representation of the Quileute, but the general air of conversation ranged from didactic to condescending, often both, because the fact of the matter is that Twilight was made by and for women, and it was profitable.

There are few pop cultural products that our society likes to shit on more than the pop culture created for teenage girls, and Twilight circa 2008 was the pinnacle of that phenomenon. This was a franchise that was built for teen girls, marketed to teen girls, and loved by teen girls, and because of that, it became accepted common knowledge that all correct-thinking people could only despise and revile it. So when I look back 10 years later, I find it difficult to untangle my hatred of Twilight from my own internalized misogyny, and from my profound and at the time unexamined belief that anything made for teenage girls must inherently be less-than.

Reckoning with Twilight, 10 years later by Constance Grady (quoted), Eleanor Barkhorn, Alex Abad-Santos, and Aja Romano

Its enduring popularity says something about the climate of imperfect art and the nature of what I think of as “aging into importance”, where something farther removed from the boiling pot of its initial controversy is more beloved or at least more evenly discussed in retrospect. But the divide upon Twilight’s release, and its ensuing conversations, reflect the nature of the critic versus the audience, the cultural expert versus the consumers, something I’ve mentioned that Rotten Tomatoes and other aggregate sites capitalize on. It certainly isn’t the only film to incite reactions — and it certainly isn’t the most acclaimed to do so — but Twilight occupied a particular snapshot of a popular and critically derided property that still has an impact on conversation today. Obviously, it’s a soft spot for me. But does that render its criticisms moot? No. They actively shape engagement of it.

Cut – bear with me here – to Forspoken.

Forspoken's reception was perhaps the complete inverse of Twilight's. It was a game decried as being "cringe" nearly from the get-go, without a multitude of fans to defend it. "Cringe" is actually one of the first autofills you're optioned with when you Google the game. The criticisms were all over X when its trailer released. It was roasted by streamers actively playing the game. The consensus was that it wasn't very good. And so, although I had been looking forward to it, I didn't buy it.

Recently though, there's been a kind of re-evaluation of it, with people coming to terms with the fact that it has a pretty rough story but decent combat, that it tried hard but didn't quite make it. Reviews for Forspoken, much like they did with FFXVI, cited the story as the weakest aspect. And that's understandably bad: story is a selling point for single-player games. Failing that is failing the test. This is where the distinction of ludology and narratology comes into play, and where gaming becomes a pretty neat place for critique.

One of the most thought-provoking pieces I read on Forspoken involves a deep dive into the why of the reaction. Why did everyone agree that this wasn't the approach to world-building dialogue they should have taken? Where is all of this sudden ire coming from? What does this say about the larger culture?

But the thing is: When I sign up to go to the mystical world of Athia, ruled by four sorcerous Tantas and cursed by mysterious blight...I'm here for the artifice! I'm on board for ominous [sic] rhyming god-queens, and I'm not sure why Frey—for whom this is not artifice, and instead is her life, is not on board for it. All of which is to say that for me, it's not so much that "the writing is cringe." It's that Frey herself is cringing, and by proxy there is a sense that the writers are doing the same.

Post-Cringe: Forspoken and the Self-Sabotage of the Smirking Protagonist by Austin Walker

The importance of this discussion isn’t necessarily in the essence of Forspoken as a story, or even as a game. It was, rather, in the prompted responses to the very idea of what constitutes good dialogue, what we can excuse in the story with good gameplay, and what this means for AA games with big ambitions. It evokes wider questions. Gamers clearly took these discussions on, by fans, by people who work in these kinds of cultural spaces for a living and for fun, unpaid and paid. For all the derision of players at its dialogue, the genuine work of critique took place inside that reaction. The reviews, the rebuttals to them, the essays on wider cultural symptoms, all of it is foundational to how we consume and discuss games, both the ones we like and the ones we hate.

All your opinions belong to us

I think anyone can appreciate what we presume is “high culture”, but I also spent my teenage years wringing my hands and telling my teachers that I didn’t think “literature” was a real thing, because — although I didn’t realize this at the time — I thought the differences were classist and unrepresentative of wider tastes. I disagree with my younger self to some extent, but it’s more complicated than “this is good art” and “this is bad art.” Art is a symptom of percolating personal and culturally influenced ideas. We should trust those who study it. We should trust those who practice it. We don’t have to agree with them on it.

In a more competitive world where low viewership results in cancellation (why didn't you all watch Inside Job before Netflix cancelled it, you cowards!), vitriol might be the byproduct of a cultural rift, one that runs parallel to the "high" versus "low" brow art argument. When companies that produce art value bottom-line profits, it feels like we have to fight, because if the company producing something we like fails, we lose that something we like. The discussion of who belongs in video game critique is then a loud "everyone", but there also has to be an understanding that not everyone understands how games work, are made, and might not be experts on a particular subject regarding them. Audiences must be discerning of who they believe, who they chose to elevate, and more closely scrutinize those outputs.

TikTok is already having a reckoning. Fans, casual watchers, taste curators — these exist on social media to open the door for new people to experience the things they love. But we shouldn’t call them all critics. That doesn’t mean they don’t have a place, it just means their place is being carved out alongside critics. The one myth we have to dispel is that critique is critical. It isn’t. It is a discussion. It is an art form. It is a conversation on the medium as it exists, with commentators (which is, I think, a better name) able to pull apart and dissect the art, not without bias, but with knowledge and expertise. You can just be nice about it when you want to, or mean when you don’t, and that’s kind of up to you.

He [German critic and film scholar Siegfried Kracauer] argues that films aren’t just documents of a culture’s values and chosen narrative tropes, but a kind of document of a culture’s subconscious, one that filmmakers often don’t know that they’re making.

Why cultural criticism matters by Emily St. James

Having finished FFXVI, I can say that I enjoyed my time, but I enjoyed my time less thanks to its absolutely abysmal side quest system, which made completing the game in its entirety a daunting checklist of meetings and follow-ups. The fault was, at first, in the placement of them, but then it became the premise of them, and then the actual world behind them, which revealed my overarching dissent: I didn’t really like the lore. The game I’d defended against critics before I even played it was now something I criticized. And yet, regardless, I still loved it.

Good or bad isn’t the point, the point is what you subjectively take from an art piece. Even the things we don’t like can elicit a powerful response (that’s why people call it “hate-watching”), and perhaps help us understand them better through deeper dives. Critique creates complexities and personalizes art. When all of us put our subjective opinions together, we get a sense of scope, an opportunity to understand other perspectives or to doubt them, to learn from people we trust and scrutinize and laugh with and celebrate creators. To do a little of that inside work.