Searching for Wonder in a Toxic Gaming Landscape

Pulling back from the brink

In January 1968, British science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke wrote to Science magazine to articulate what would become the third and final principle of his now famous “three laws”, a set of observations about technology, discovery, and humanity’s relationship to them. In this, the most famous of the three adages, Clarke stated: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic."

Starting Early

Fast forward thirty-two years, I’m six years old, and I’ve invited myself round to a friend’s house under the pretence of a sleepover.

In reality, I was there because I knew he owned a PlayStation.

Up to that point, I’d only ever had a passing relationship with videogames. A friend’s birthday party here, playing pinball on the family PC there; but outside of that, my chances to play had been slim to none.

After some debate, we settled on the latest addition to his collection: a game called Action Man: Destruction X. We slid the disc into the tray, the CRT flickered to life, and then, the sonic boom etched into the skulls of millennials the world over.

After negotiating a menu screen and the opening cutscene, the television gave way to the game itself. There was my childhood hero rendered in glorious, pixelated form - equipped with only a boomerang - facing off against a Tyrannosaurus Rex in what felt like a chasmic arena. Now, I don’t wish to be hyperbolic, but at that admittedly early point in my life, this was easily one of the coolest things I’d ever seen. To me, it was indistinguishable from magic.

Why Videogames?

It didn’t matter that the game was clunky, borderline incoherent and, on reflection, somewhat shit. What mattered was the feeling: the sense of discovery, imagination, and possibility that videogames offered in a way nothing else quite did. That moment set the tone for a lifelong relationship with games, a medium in which I could explore entire worlds built with care, craft, and creativity.

But somewhere along the way, something curdled.

If I really interrogate why I still play videogames, I’d say that they’re a way for me to reconnect with that younger version of myself, a window I can slip through to retrieve some of the wonder that came so freely in childhood, but which adulthood takes too readily. Games still do that for me, but increasingly, the culture which surrounds them seems determined to crush it.

Gamerhate

It’s not hard to see why. Today, social platforms shape much of the conversation we have about games, and those sites - Twitter, Reddit, YouTube - are designed first and foremost to reward engagement, not understanding. Invariably, then, nuance doesn’t travel; anger does, and in gaming spaces, that anger metastasises quickly.

The depressing part is that the warning signs have been there for over a decade. Flashpoint moments like Gamergate didn’t mark the advent of toxicity in games; they marked its industrialisation, with harassment campaigns masquerading as “consumer advocacy,” sustained abuse directed at developers and critics, and a lasting lesson learned by bad actors in the community - outrage is profitable. Later crossroads, like the backlash to The Last of Us Part II, followed the same template: review bombing, death threats, and petitions demanding creative works be rewritten to better align with audience entitlement. These moments matter, but not because they’re shocking. They matter because they’re no longer exceptions.

Where Things Stand in 2026

This pernicious behaviour is a dime a dozen today. A studio’s creative decisions are pre-emptively litigated on social media before a game even releases - for example, Bungie’s Marathon hasn’t even been released yet, and it’s already being dissected and denounced online. Developers don’t have to worry about abuse; they expect it. Marginalised players quietly disengage, not because they don’t love games, but because the surrounding culture keeps reminding them they’re not welcome. The question, then, is simple: is this the culture we want to exist within, at a time when games are pushing the medium further than ever?

Videogames today are more ambitious, more expressive, and more artistically confident than they’ve ever been. Yet the way we talk about them, publicly, performatively, online, has grown smaller, meaner, and more caustic. Games are treated less like shared experiences and more like battlegrounds where identity, politics, and personal grievance collide.

Assmongold

I’d like to apologise in advance for this next example. Earlier this week, my Twitter algorithm served up this little gem for my viewing displeasure. Go watch it, I’ll wait…

Now, to me, Asmongold is amongst the worst offenders in turning our modern gaming culture into such a poisonous place. In this clip, he neatly illustrates why. Here is a prominent streamer, with a sizeable audience, openly expressing a willingness to make the lives of strangers more difficult on a whim, and framing it as entertainment. There is no insight here, no critique, no value, just spite, amplified by a platform that rewards it.

Asmongold is not a thought leader, a cultural authority, or a policymaker. He is a Twitch streamer whose influence far outweighs the responsibility he shows in wielding it. And every time his behaviour is normalised, rewarded, or defended, the culture around games becomes a little more hostile, more fractured, and less worth participating in.

Superbold

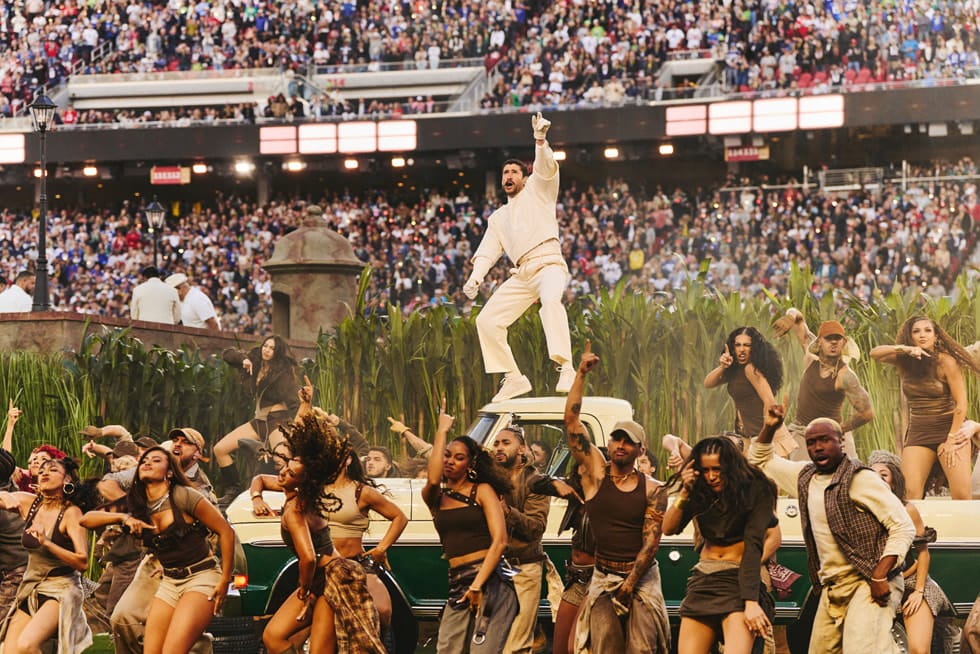

If you’ll allow me to zoom out further for a moment, this behaviour isn’t confined to games; it reflects a broader pattern playing out across society in general. Just this past weekend, Bad Bunny performed at the Super Bowl LX halftime show, and I’ve watched as some of the world’s pre-eminent grifters and walking, talking human mudslides have used this not as an opportunity to widen their world, but instead to foment hatred along national and ethnic lines.

It’s tempting to dismiss this as a “bad fans” problem. It isn’t. It’s a systemic one.

Platform incentives reward outrage. Algorithms flatten complexity. Identity becomes tribal. Disagreement turns instantly into moral failure. In that environment, games stop being art to engage with and become symbols to defend or destroy. The loudest voices dominate, not because they’re representative, but because they’re profitable.

This all has consequences; not abstract ones, but real, human costs. Developers burn out or leave the industry entirely. Players self-censor or withdraw. The medium’s public reputation is shaped not by its best work, but by its ugliest behaviour. It only makes it easier for traditional media to dismiss videogames as immature or unserious, and why shouldn’t they when the culture surrounding them seems so allergic to reflection?

What Next?

This is the part where I’m supposed to present a solution. I don’t have one. Not a clean one, anyway. But I do know what I want.

I want a gaming culture that remembers games are made by people, that creative risk isn’t betrayal, that discomfort isn’t failure, that art doesn’t owe us validation, only honesty. I want conversations that prioritise curiosity over condemnation, and criticism that engages with craft rather than identity.

Most of all, I want us to reclaim the magic that drew so many of us here in the first place. With that in mind, I’ve compiled a list to help move the needle back to a more acceptable, more human place, a ruleset that I like to call…

Ten Rules for Being Less Awful About Videogames

- Remember that games are made by people - Not brands, not avatars, not targets. Real people with finite time, energy, and feelings. If you wouldn’t say it to their face, don’t post it.

- Disliking a game is not a moral position - You didn’t like the story. Fine. You hated the mechanics. Valid. That does not make you enlightened, betrayed, or oppressed.

- Criticism is not the same thing as harassment. Learn the difference - “This didn’t work for me” is criticism. Dogpiling, threats, doxing, or abuse dressed up as “feedback” is cowardice, nothing more.

- Art is allowed to challenge you, frustrate you, or leave you cold - A game failing to meet your expectations does not mean it has failed outright. Sometimes the work isn’t bad, and challenging you was the point.

- Stop treating developers as customer service reps - Buying a game does not entitle you to control its creative direction, rewrite its story, or demand it be remade to suit your tastes.

- Engagement is not truth - The loudest take on Twitter or YouTube is rarely the smartest one. Algorithms reward outrage, not insight. Don’t confuse virality with validity.

- Gatekeeping kills communities - There is no “correct” way to enjoy games. If your instinct is to test someone’s credentials before welcoming them, look inward.

- Punch up, not down, or better yet, don’t punch at all - Mocking the corporations that pick apart the industry is fair game. Harassing individuals, especially marginalised ones, is not rebellion; it’s cruelty.

- Log off when you’re angry - You don’t owe the internet your worst impulse. No take is so urgent that it can’t wait until you’ve cooled off.

- Protect the thing you love - If you care about games as art, act like it. That means curiosity over contempt, empathy over entitlement, and remembering why games felt like magic in the first place.

When all is said and done, I’d like to leave you with this.

In Blood, Sweat, and Pixels, Jason Schreier recounts a conversation he was having with a developer, after hearing about a gruelling production cycle, “Sounds like a miracle that this game was even made.”

“Oh, Jason,” the developer replied. “It’s a miracle that any game is made.”

I wish the people who claim to love games remembered that.