The Dichotomy of Difficulty

Making challenge fun

Armored Core 6 has been an interesting game to follow since its release. This is the first time that the franchise is in the spotlight thanks to the success of From Software’s Souls-like games. What’s surprising is the amount of backlash it seems to be getting when it comes to talking about difficulty, which frames an important point that I’ve been thinking about for a while: a lot of people don’t understand difficulty in gameplay.

Where the AC Hits the Road

Armored Core 6’s difficulty can be described as peaks and valleys. The very first peak is with the tutorial boss helicopter, who is there to teach you the combat fundamentals — specifically, be aggressive. The next, and more famous at this point, peak comes with the chapter 1 fight Balteus. The difference between the two is that the first fight is strictly to teach the player combat, while the second one combines this with the game’s AC building.

Source: YouTube.

I’m going to talk more about this in a separate review, but Armored Core 6 is unusual in a way for the genre. This is a game that requires action reflexes as well as an understanding of RPG abstraction and build design to win. You can’t just have one — without the reflexes, you won’t be able to survive the bosses; without the builds, you won’t be able to have an AC that can fight. For me, I settled on an aggressive high-speed close to mid-range build, and then I tweaked and built my AC to capitalize on it. The battles that took people hours to beat, I did them in 10 minutes apiece; the hardest boss for me took about 20 minutes of playing. Being able to understand what the game wants of the player goes hand-in-hand with how it facilitates that challenge.

What Creates Difficulty

Difficulty design in any game is built on two variables — what the game wants the player to do and the player’s own skill at that gameplay. When a game's difficulty and gameplay are not in sync, those things that make the game challenging are thus inherently opposed to the gameplay presented. This is where I often talk about the differences between challenging and difficult gameplay. If a game is all about dodging projectiles, and the designers purposely make projectiles hard to see and move very fast, then that would be a clash between design and difficulty.

The player’s own skill level is the X factor for every game. As a designer, you won’t know what skills the person behind the keyboard/gamepad is going to bring to that game. You may have someone who has thousands of hours of practice in the genre, or you may have someone with literally none. Good onboarding is needed to get the latter group up to speed.

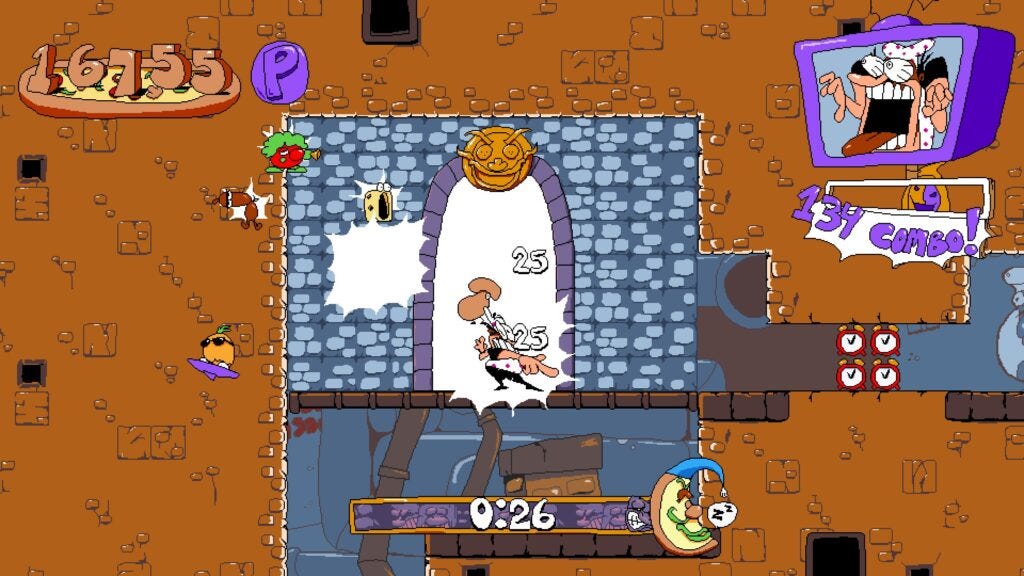

Another aspect of this is how high the skill ceiling of a game should be. Some people feel that progression means a linear curve of difficulty — if level 1 is a 1 out of 10, level 20 should be a 20 out of 10. That’s not the case, because higher difficulty doesn’t translate into better gameplay. It’s more about providing different ways of challenging the player that are, in and of themselves, easier or harder. One of the aspects I loved about Pizza Tower is that the game’s ultimate challenge of P-ranking the stages did not require perfect mastery. This is in contrast to Crash Bandicoot 4 where you did need 100% mastery on each stage to the point that it just became painful to do.

Pizza Tower is a good comparison to Armored Core 6, in that both games are played by their own rules, and your overall enjoyment and progress in each will be dictated by whether or not you learn them. Here’s where it gets tough to understand difficulty: there is a difference between a game that is designed to be difficult and a game that you find to be difficult.

The “You” Problem

When I see people have a defeatist attitude about being stuck in a fight in a skill-intensive game, there is another factor here that no one wants to hear — maybe the problem is you. I’ve written many times about why I’m not a fan of the concept of player-centric design, or that a game must be designed so that everyone can play it, and how it ends up creating games that are very flat in terms of their design.

Not every game is meant for everyone, and From Software is a studio that embodies that. Could they make their games easier? Definitely, but that’s not the style of their design, and that’s perfectly okay. Part of the challenge of designing for difficulty and studying games is trying to piece together what aspects are stopping someone from playing it as I discussed above. When most people think about playing a game, they see it as a one-way commitment — the developer puts out a product that is meant to be easily consumed and that’s it. In this respect, any time the player has trouble in the game is innately a problem of the designer.

However, when I talk about games that are designed around a challenge, that commitment becomes two-way — the developer puts out a product and you as the consumer have to meet the expectations set by the designers. A lot of people do not like difficulty in their games, this is not the same as challenge. If someone is a master at platforming or fighting games or whatever, playing a hard version of that is considered normal because they have that background. Put those same people in front of a genre that they don’t know, a game that is hard and that they will fail at, and there’s a good chance they will buckle. This is what I'm seeing from the people who have grown accustomed to the Souls-like formula; they are hitting the very same wall of difficulty as the people whom they once told to “git gud” when attempting to play From Software’s other titles.

Understanding challenge is something that takes a lot of time to master when you study design. You need to be able to comprehend not only the aspects that the designers want to test, but your own shortcomings and skill at the same time. I’ve said this before, I can study any genre that I want, even the ones that I’m terrible at, and that’s because I understand what the gameplay loop is trying to test. There’s a difference between a game that is hard because the gameplay itself is not working right, the UX is off, etc., and a game that is hard because “I” can’t do what the game asks of me. This is the part of game analysis where you need to look at the developer’s intent and use that to deduce if the game is facilitating it.

Armored Core 6 is by far the easiest game, in my opinion, From Software has put out in over a decade. The people who say it’s too hard because you have to modify your AC and the ones who say that it’s too easy because you can modify your AC are both wrong to some extent. I’ve seen this kind of game countless times from the indie space — a title that challenges the player to figure out the solution to the problem; heck, that’s Zachtronics games, and logistics games, in a nutshell. The difference is that Armored Core has a far greater spotlight on it than those games. Beating a tough boss in Armored Core 6 using the perfectly itemized list of parts designed to counter it is just as valid as taking the opposite build that you are going to struggle with. As a brief aside, we collectively need to start getting away from discussing “legitimate” ways of beating the game if they purposely ignore the mechanics or systems placed by the designer.

I believe the reason why the backlash seems greater here compared to the Dark Souls series is that a lot of people now playing this expected their skills to translate 1:1 to Armored Core 6, or that the game itself is just Dark Souls 4, but that’s not how it works. This is more akin to Sekiro in that the game has its own language of combat that you need to master. Do it, and the game is effectively done; don’t do it or don’t want to do it, and you’re not going to be able to play it. And that last sentence is very important. If a game is set up to require certain skills or understanding of the mechanics, and someone purposely or stubbornly refuses to do that, then there isn’t much more you can do as a designer. However, if someone is trying to learn those elements, and the game is fighting them, then that’s a problem for the design team to look at. This leads to a larger talk about onboarding and UI/UX design which is too big to get into here. There are some legitimate issues with the design and structure of Armored Core 6 which I will talk about in my review, but difficulty is not one of them.

Going back to Sekiro, I was very critical of that game by the fact that it removed all choices and builds as viable options and instead just focused on one way of playing it. The reason why it was overwhelmingly praised was that it was just a continuation of the design that people already knew and that their skills could translate to some extent going from Souls-likes to that new game.

There’s nothing wrong with bouncing off a game, but immediately saying that it’s the game’s problem or the game’s fault is not how you do a critical analysis or try to grow at a game. And again, there is no shame in bouncing off of a game because it’s not working for you.

Critical Difficulty

Difficulty and challenge are often considered one and the same, but the problem is how things are perceived by the player. There are games that are brutally difficult which experts can find boring, just as an easy game could be an ordeal for someone who is not prepared. Like I always say, difficulty is not an inherent metric of quality for a game, an idea I’ve been thinking about while writing my book on Souls-like design. Too many people think that if they struggle with a game then it must be a deep and rewarding experience, just as people who get stuck in a fight feel that the game is obviously bad.

Ultimately, the best judge of challenge in a game comes down to this one point — does the game provide you with everything that you need to succeed and convey that to the player? If a boss fight is strong against fire damage and I stubbornly refuse to equip any ice spells, is it the game’s fault for forcing me to switch my build? But if I know the boss is weak to ice magic and the game does not give me any way to take ice damage to that fight, then I experience a breakdown in the difficulty.

As an example of when things aren’t working right, I recently hit a frustrating wall playing Turbo Overkill on the highest difficulty, which has received several patches to make it harder.

At the point where it is at now, the arenas don’t feel like they are set up to work with the abilities the game gives you. In one, I was killed within seconds at full health from enemies with infinite range before I could even spot them. And this is compounded by enemies doing far more damage, and having their projectiles being literally faster on the higher settings. The damage from environmental hazards has been tweaked and you can still get hit by stuff on the ground even if you’re jumping. It’s a case where all the tools and tricks the game gives you, feel like they punish you for doing anything but the one specific solution and being lucky.

It reminds me of how The Ancient Gods Part 1 DLC for Doom Eternal felt — where instead of having interesting arenas and battles, it just felt like designing frustrating encounters that also go on for too long given the difficulty. This is why it is very hard to properly balance games that are either explicitly or implicitly designed around different difficulties.

And again, no matter how much praise games like Elden Ring received, or how famous the From Software brand is, these games are still niche experiences in the grand scheme of things. There is nothing wrong with enjoying brutally difficult games just as it’s fine if you want to play casual experiences, but demanding that one is considered “better” or “worse” than the other is where I run into a problem with the discourse.