The State of Indie Games in 2025 and Beyond, Part 1

Diving deep into the state of the industry

Every year is a magnificent year for indie games - and also a terrible year.

Between the dawn of a new console generation, the delay of some of the industry's biggest titles, and the long-awaited release of others, 2025 has offered small developers a narrow avenue of victory. But how does one achieve that? As the video game industry has expanded and opened up, the keys to success have grown more complex.

There are hundreds of factors determining the games you get to play and whether the people who made them get to reap the rewards. Which genres are the money makers, and which are the dead ends? How do developers navigate a market where a generation's worth of games come out every few months? Who funds smaller games, and what happens when that investment money goes away? How are new tools and technologies changing the game? And what black swans are over the horizon, ready to turn everything upside down?

I've been keeping tabs on this part of the industry for five years. Some of the issues facing these developers are evergreen; others are brand new. All are changing the future of video games.

It's one thing to run down the stats, but no one understands the trials of development like a developer. So I asked around. The following individuals and groups agreed to answer my questions:

- Advonger Games, developer of Realms of Madness

- Amistech Games, developer of My Summer Car

- BenBonk, developer of Slimekeep

- bit ManiaX, developer of V's Rage

- Broken Bird Games, developer of Luto

- Burgee Media, developer of Erenshor

- Cyan Avatar Studios, developer of MoteMancer

- DYSTOPIAN, developer of Gnomes

- Roger Gassmann, developer of Pax Augusta

- Green Tree Games, developer of Burden of Command

- Grundislav Games, developer of Rosewater

- Hammer & Ravens, developer of Ale Abbey - Monastery Brewery Tycoon

- Happy Volcano, developer of Modulus

- Human YoYo, developer of CleanFall

- Keen Software House, developer of Space Engineers 2

- Kipwak Studio, developer of Wizdom Academy

- Kylyk Games, developer of Urban Jungle

- Joshua Meadows, developer of Alcyone: The Last City

- Mostly Games, developer of PEPPERED: an existential platformer

- mrkogamedev, developer of Metro Gravity

- Paintbucket Games, developer of The Darkest Files

- Powerhoof, developer of The Drifter

- Sleepy Mill Studio, developer of Drop Duchy

- Sobaka Studio, developer of Kiborg

- SolarSuit, developer of Static Dread: The Lighthouse

- squid_lawyer, developer of Mage Tower Massacre

- Steelkrill Studio, developer of The Backrooms 1998

- John "Ducky" Szymanski, developer of Secret Agent Wizard Boy and the International Crime Syndicate

- Team Machiavelli, developer of Castle of Alchemists

- Trese Brothers Games, developer of Cyber Knights: Flashpoint

- Zero Sun, developer of Astral Throne

If you'd rather hear me read the article, check out the video. Source: Youtube.

Again, the list of factors affecting indie game developers is almost beyond counting. However, there are a few big ones that came up repeatedly from developers, press, marketers, and the public at large. I've winnowed this down to fourteen key takeaways that are important now and will likely remain important for the foreseeable future.

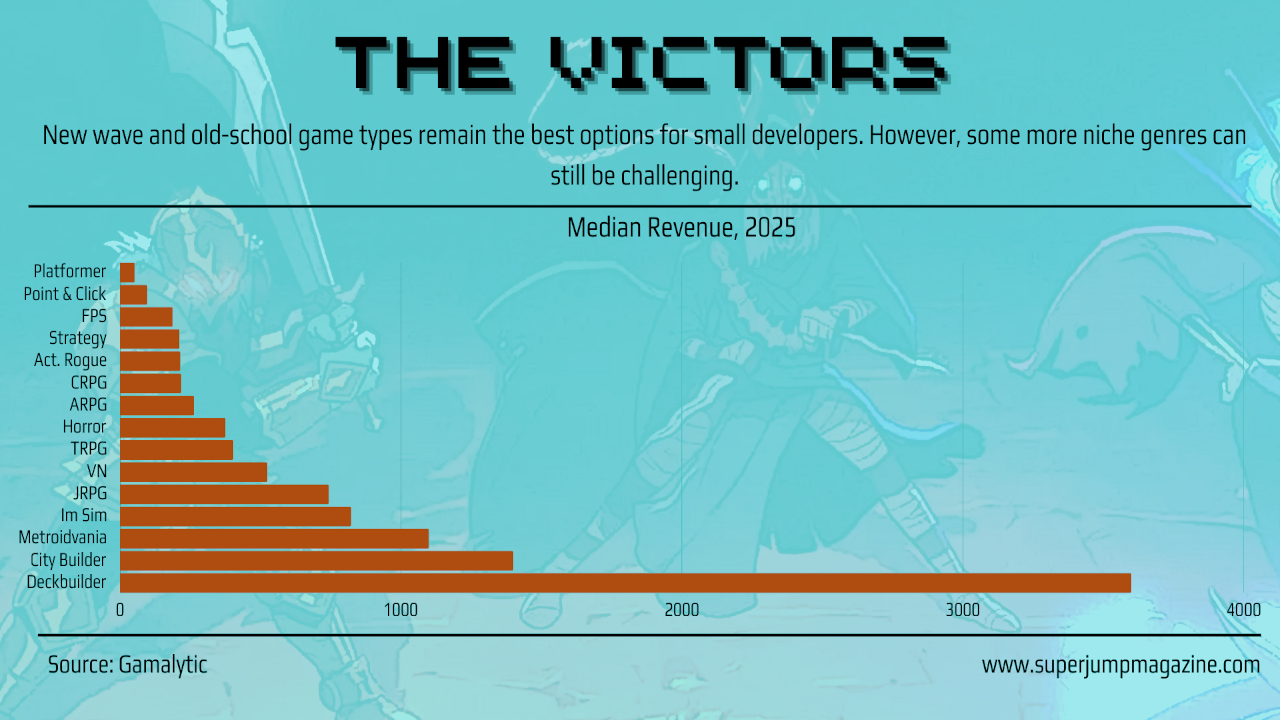

Emergent and old-school genres are still the best for developers

The modern gaming environment contains a multitude of genres, but they aren't all equal. AAA developers are known for sticking to a handful of safe, proven genres at any given time, releasing the same basic games on a regular cycle. There's far more liberty among smaller developers, and the choice of genre is one of the most important factors affecting a game's success.

The general rule hasn't changed: Indie developers are strong where A-tier developers are weak. These stronger genres fall into two very different categories. First are the new wave genres essentially developed in the indie space, including open world survival, deckbuilders, and some roguelike subgenres. Second are traditional genres largely abandoned by A-tier companies, including city builders and many RPG subcategories. These are far and away the safest for upstart developers, as there is less risk of being overshadowed.

Horror is a perennial example of a genre in which small developers have an edge, and Borja Corvo Santana of Broken Bird explains the advantages: "It is also a genre that in some way facilitates the entry of many developers, both because of the ease of making a horror game where the interest lies in fear and not necessarily in the mechanics, and because of the players, who normally value all kinds of works, some of them even very amateurish."

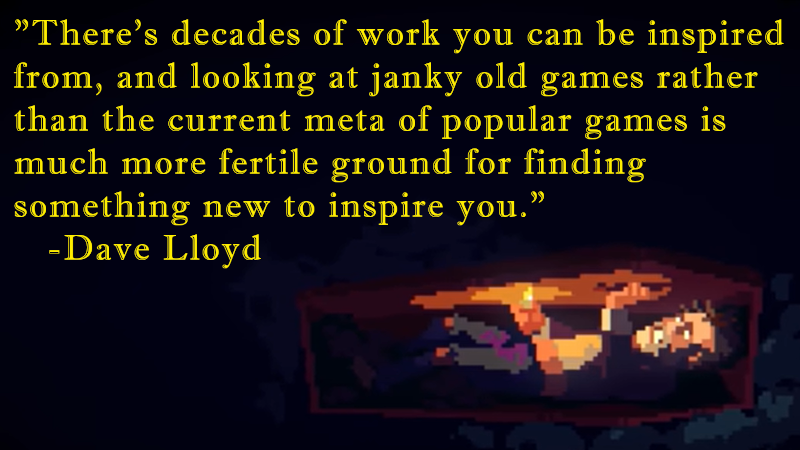

But everything is relative, and competition in some of the more profitable genres can be intense. Several of the surveyed developers have games with roguelike elements. For several years, this has been a popular style among small developers. It's easy for them to manage while also being broadly popular. As the style has matured and grown in popularity, it has taken more work to get noticed.

"The genre is bigger than ever, and is growing like crazy," says Slimekeep developer BenBonk. "That being said, the competition is much fiercer and seemingly every week there is a new flashy roguelike with a catchy hook like [insert traditional game here, such as chess or roulette, etc], but a roguelike. So developers can obviously find huge success in this genre, but need something to differentiate them more than ever."

This hints at something important about the current market: It's no longer enough to make a good version of a popular type of game. Something so standard will inevitably get lost in the shuffle. For a game to succeed, it's also necessary for it to have a unique hook.

"I think the Automation genre still has a lot of unexplored space to delve into, and I do think that MoteMancer is carving a little more into what fantasy can do since there are so many industry-focused games right now," says Adam Kugler of Cyan Avatar. "[M]y mindset and advice for making games continues to be: make a game that deserves its place. Focus on bringing something new to the table, be mindful of what has come before, and respect the player. Any game that is mostly derivative of other games will have a much harder time finding its audience."

Some development teams deliberately target growing genres. A representative from Do No Harm developer Darts Games wrote an extended post on Reddit about the complex process they used to decide on their next title. Others go even further. "We have developed our own analytics tool that gathers data from the Steam platform, allowing us to track market trends," says Dmitrii Belei of SolarSuit. "We released a horror game with simulation elements, and during development, we noticed that, overall, the horror genre has nearly doubled in size from 2024 to 2025."

Still, for the typical developer, it's all a matter of luck. They may design a game that falls into the right genre at the right time, but it started as a desire to make something.

"Games need to be passion projects that explore some new areas and present fresh thinking," says Johannes Rojola of Amistech Games. "Calculative thinking can get you only so far - these days, probably nowhere. Doing that is still difficult and requires a lot of work, so with the same trouble it is better to do something different, new, interesting. Something the developer actually cares about."

Other genres are a lot tougher - but profitable niches exist

At the other end, those genres dominated by A-tier developers tend to be an uphill trek for small developers. These games are often directly compared to others with far higher production values, and the smaller company rarely wins those matchups. Action RPGs, first-person shooters, most types of strategy, fighting, and racing are all rough genres where even high-quality games can end up being ignored.

Comparison to AAA games isn't the only problem that can confront developers in difficult genres - less flashy games can also be a tough sell in general. "Turn-based strategy games often have a hard time standing out in showcases, social media, and other spaces that favor fast-moving, easily 'clip'-able games," says Jay N of Trese Brothers. "The death or corporate gutting of so many game news sites really hurts genres that need someone to invest more time into a game and summarize a deeper / more complexly fun experience than can be communicated in a GIF."

Traditional adventure games are another interesting genre to examine. They're harder to pitch as they're not very dynamic, but have a well-defined audience that's larger than people think. Several responding developers released adventure games this year, and their perspectives run the spectrum.

"The general market is not favorable for the kind of serious games we make," says Jörg Friedrich of Paintbucket Games. "The games we are doing are certainly niche - however, since almost no one else is catering to that niche, we can live from it."

"Thankfully, there's still a demand for narrative/point & click adventure games," says Francisco Gonzales of Grundislav Games. "However, it's now even harder to get noticed. It used to be hard enough to get any coverage or attention as an adventure game in the indie game sphere; now there's the added challenge of breaking through all the other amazing adventure games being developed."

Niche genres can be a great opportunity for new developers, but they can shift from good to bad without warning. Small, underserved communities are open territory that get crowded in short order.

Like the games in winning genres, the ones in tough genres still succeed or fail based on their innovative traits. A game made in a fiercely competitive or narrowly popular style can still make a mark if it contains something new and exciting.

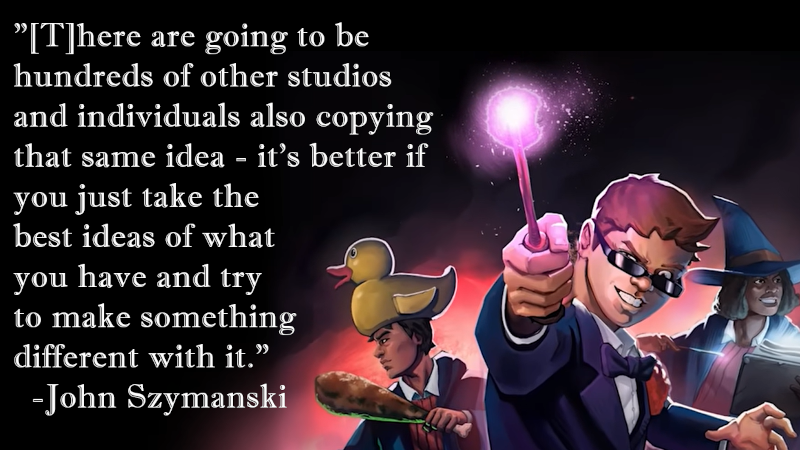

"[I]t's really easy to see something that does big numbers and just feel like you should try to copy that to ride the wave," says John Szymanski. "In reality, there are going to be hundreds of other studios and individuals also copying that same idea - it's better if you just take the best ideas of what you have and try to make something different with it."

Multiplayer (especially co-op) is a major force

"[O]nline multiplayer is a really big selling point right now, so even if there's a lot of competition in that space, there's still a pretty hungry market for it," says Szymanski. "I'd never recommend making a multiplayer-only game (it's a bit of a roll of the dice whether it will work out), but with something like Secret Agent Wizard Boy, where the game functions as well with multiple people as one person, there's not a great reason not to at least entertain the idea."

Many teams are now pursuing multiplayer features, whether that's true multiplayer or less significant networked features. According to the 2025 Unity Gaming Report, a majority of developers are working on games that are primarily multiplayer, including a plurality of teams with fewer than six people. By contrast, very few teams are working on games that have no online features whatsoever. In a networked world, even something as minor as a leaderboard can make a difference.

However, the real winner for 2025 has to be co-op multiplayer. The popularity of Chained Together in 2024 already suggested that co-op could be a big deal, but the smash success of R.E.P.O. and Peak - both among the year's top-selling indies - is solid proof.

This is hardly the first time that co-op has been big, but there's a specific dynamic at play that favors smaller developers. The modern co-op environment doesn't have a lot of matchmaking - even if the games are online, people prefer to play them with real-life friends. This means that prospective players have to talk 3-5 of their friends into buying the game as well, and price carries a lot of weight. It's far easier to convince someone to roll the dice on a $10 game than on a $60 game. As such, it's unlikely that A-tier developers will have the same success should they try to enter the co-op space with their premium-priced titles.

There's another wrinkle to the success of these budget-priced co-op games. The average play time is very low compared to most live service and online games, with R.E.P.O. players averaging just six hours per month. This could be because of what you might call "non-traditional gamers" - people for whom video games are not a significant part of their lives. Early adopters are bringing non-game-playing friends into the indie space.

This doesn't mean those people are going to stick around, but it's one area where small developers have made definite inroads.

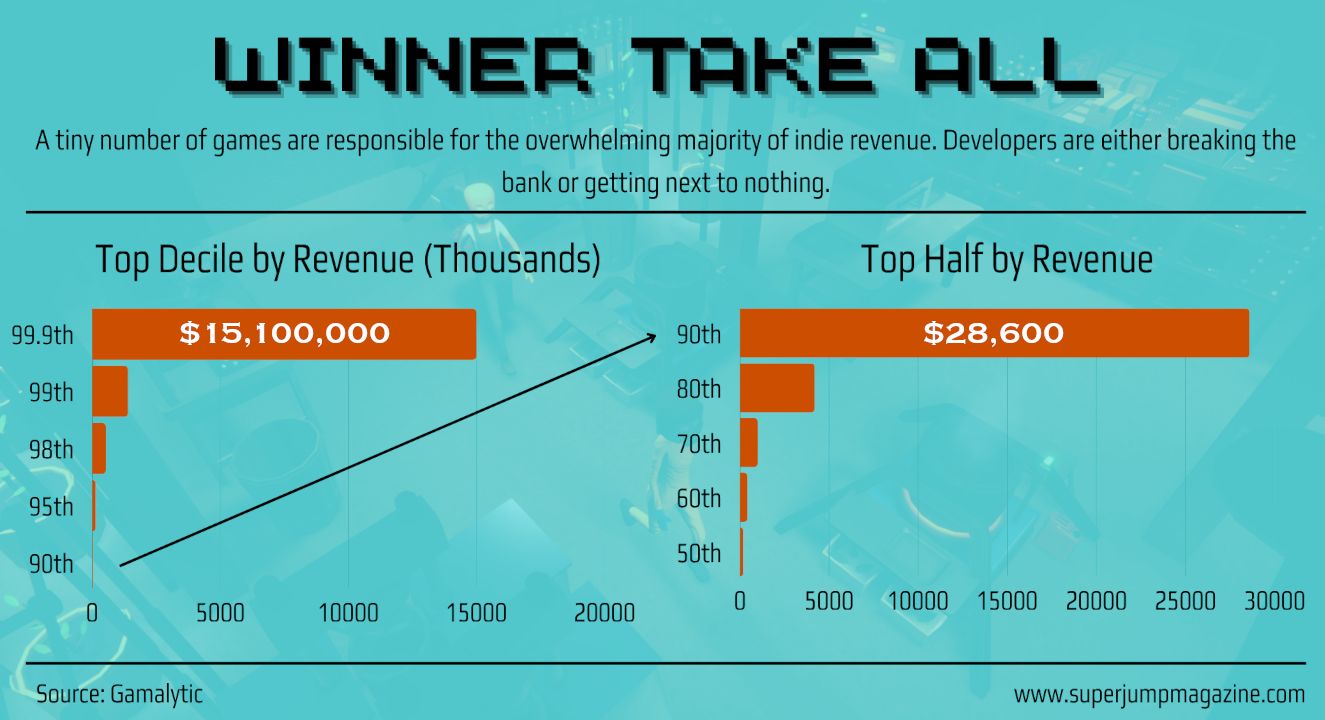

Modern indies are winner-take-all

In a typical year, indies generate revenue somewhere between $2 billion and $3 billion, and that money is not equally distributed. Games from well-known studios, titles with trending gameplay styles, and viral hits are responsible for the lion's share of the money. In 2024, a record-setting year, the top 1.5% of indie games (those making approximately $1 million or more) generated more than half of all indie revenue.

This feast-or-famine environment is also clear at the individual level. The median indie game in 2024 made around $180, with games at the 30th percentile generating $30 or less. This increased to $28,600 at the 90th percentile, $1.4 million at the 99th percentile, and $15.1 million at the 99.9th percentile.

While this resembles the consolidation that we've seen in the A-tier space, I believe there's a different dynamic at play here. The indie market is not concentrated, but rather driven by hits. 2024 was a great example of this dynamic, as Palworld generated about half a billion dollars itself.

Put simply, the strength of any given year is based on how many breakaway hits there were and how big they became. For the typical developer, little has changed on the sales front over the past half-decade. The main issue is one of expectations. A developer assuming that they'll sell a million copies is likely to be disappointed, while another developer with more realistic expectations can still do fine.

"By the metric of, say, Schedule I, the games I make are only tapping into a small fraction of a percent of the market base as a whole - the difference in sales is on orders of many, many magnitudes," says Szymanski. "But to me, my journey so far has been greatly successful in that I've made enough on a month-to-month basis to be comfortable, reached a lot of people, and have been able to keep a couple of other developers afloat through a really rough patch in video game development jobs."

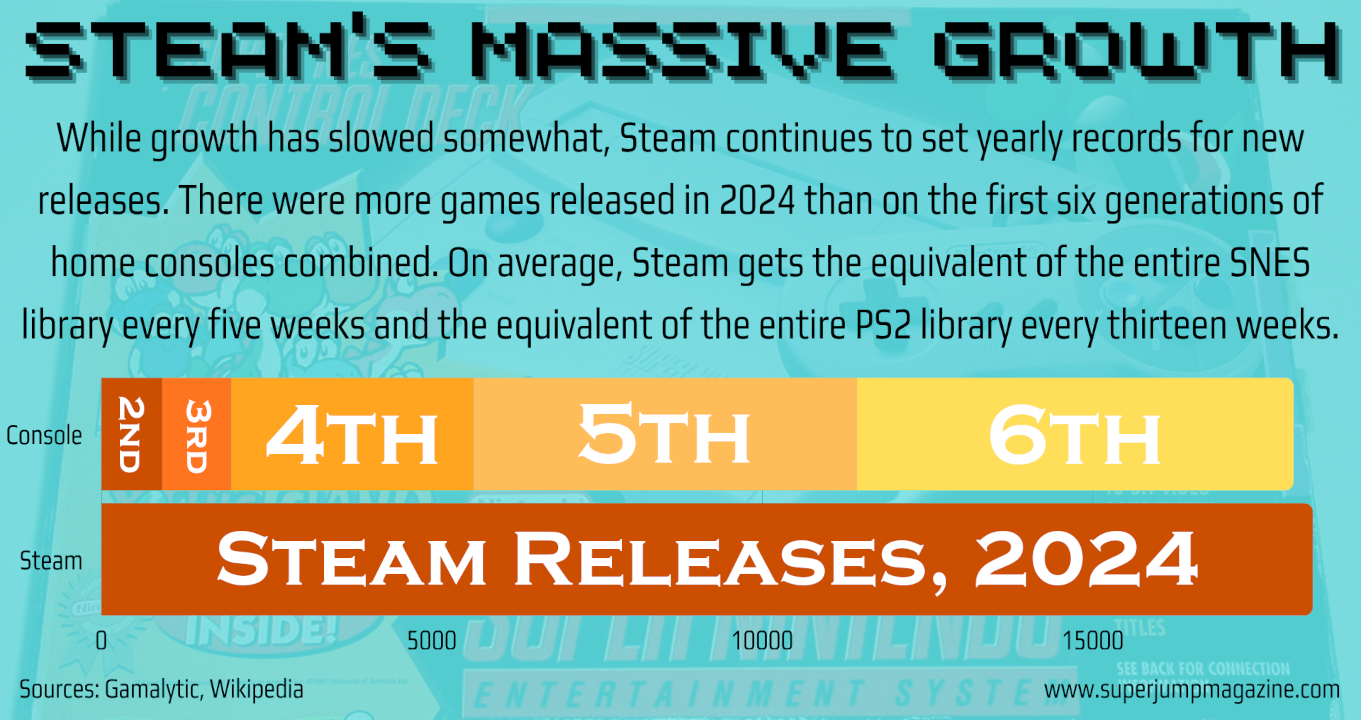

Steam is still growing out of control

This talk about hits and misses is skirting a major issue, one that almost every developer brings up: There are a massive number of games coming out every year.

The growth of the Steam library is an evergreen topic. The rate of growth is slowing down, but 2025 is still likely to be another record-setting year, with the total size of the library approaching 150,000 titles. On average, more than 300 games hit the storefront each week. The launch window for a game is important for most indies, so dropping that game in a strongly competitive week can have brutal consequences.

Many developers list this among their challenges. Joshua Meadows offers a representative comment: "In the same way that things are more accessible than they ever have been before, I think there's more over-saturation than there ever has been. It's very difficult for smaller or independent developers to get attention and break through the noise and I think a lot of very good games go ignored because there's just so many and there's only a certain amount of attention available."

Steelkrill offers a similar sentiment: "In such a saturated market, it's really easy for a small developer to go completely unnoticed. [I've] seen some great-looking games get no love at all. Then I've seen some not-so-great games, going viral."

The quantity of releases is assuredly an issue, though I've always wondered if it's as impactful as everyone thinks. The age of indie shovelware is over, but a lot of smaller games still have an unpolished, unprofessional look that makes them far less competitive. I've done a bit of a dive into that myself. After reading a thread by a Reddit user analyzing every game released in a 24-hour period, I did a cursory comparison of trailers for games at different revenue tiers. There's a marked difference between your typical game at the 75th or 95th percentile and one at the 30th percentile. The latter are hardly competitive, and they only get worse below that line.

Source: YouTube.

I'm comfortable saying that most of the games hitting Steam, while better than the median indie from a decade ago, are still unexceptional. In an environment like this, reaching a baseline level of professional competence can be enough to stand out, if insufficient to achieve broad success.

Steam discovery is getting less useful

But there's a related issue that makes this massively overcrowded market even harder to break through. Steam - still the main home for small developers - has its own share of internal problems.

"Steam’s 30% cut drains a significant amount of revenue from developers for a platform you increasingly have to bring a lot more traffic to yourself to get any real boost from," says Jay N. "Steam’s analytics and reporting are ancient, frequently unreliable, and difficult to turn into anything actionable. Support is hit or miss, even if you’re a studio that drives hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue for them. Lots of featuresets (Steam curators, groups, large chunks of Steamworks) haven’t been updated in years."

That first point is particularly important. A recent Newzoo analysis demonstrated that the proportion of internal traffic driven by Steam has declined significantly over the past five years. Steam's discovery system is now less effective, as are most types of sales. This means it's more important than ever to gain attention from outside of the platform. It's an environment that favors larger, established teams and games from famous IPs.

This isn't a secret to developers, and it's widely known now that success depends on drawing attention before launch day. "Steam’s algorithm rewards traction, so unless your game starts generating revenue quickly, visibility will be limited," says Burgee Media. "That means your pre-launch marketing, community-building, and product positioning need to be on-point before you ever click 'publish.'"

Of course, for those who are able to find that early traction, the system can work wonderfully. "The hardest part is getting enough wishlists to get Steam working for you," says Tommy McKay of DYSTOPIAN. "If you can get yourself to about 10,000 or so, you'll find that Steam does most of the heavy lifting, and all you need to do is make sure your game slaps so get good reviews and retain your players."

Marketing remains a serious challenge

Unfortunately, getting those first few wishlists requires doing something that every small developer dreads. For people in any creative field, marketing is more critical now than it's ever been. It's a stumbling block for most, either because they don't know how to do it or because they're resentful of the whole idea.

Pax Augusta developer Roger Gassmann has a lot to say about the importance of marketing: "I'm no expert, but over time, I've met many small development teams. The biggest problem seems to be marketing. 1) They lack the knowledge of how to market, and 2) it's extremely neglected. I've seen so many exciting game concepts over time that will never make it because they can't/don't advertise them."

But what means of marketing are available for resource-poor developers, and how do they know where to best spend their advertising dollars? Game developer Reddit is full of posts like this one from the developer of a game called Frostline, breaking down the relative value of advertising on different platforms. The most obvious choices aren't necessarily the best ones - and the best ones overall might not be best for everyone.

"[Y]ou can't just do run-of-the-mill marketing," says Gassmann. "Small schools don't have the budget for that anyway. The important thing is: 1) you need a marketing strategy, and 2) you should start as early as possible."

Aside from lacking the money for conventional advertising, developers are limited by the time and skills necessary to mount any real campaign. It's easy for the usual suspects to shout the words "social media" and act as though everyone has the keys to the kingdom; in reality, it's far more complex than that. Even those developers who've found some degree of popularity on these platforms have often struggled to turn that popularity into attention for their games.

And even that assumes that one is inclined to cultivate an online audience. "Other people seem to build audiences with social media, streaming, and TikTok/YouTube, but that seems like investing more time and resources into building a following there instead of directing it towards the thing you're actually trying to make," says Joshua Meadows. "I don't personally have a lot of interest in trying to cultivate a Twitch audience or Discord community that I then have to engage with, monitor, and manage to hopefully be able to leverage it into attention for my game/writing/art — other people seem to manage this so no knock against them, but it doesn't appeal to me."

For most developers, content creators are still the only viable method of gaining exposure, but these connections can be harder to make and less valuable than they were years ago. The developer of a game called Astoaria says that they net an average of one wishlist per 50 views on a video featuring their game. That's a ratio that demands either massive, broad coverage or being featured by a huge creator.

Regardless of the approach one attempts, it's clear that marketing is simply an essential headache. "[Making] great games is not enough these days, you need to research your business case and have great marketing," says Jeroen Janssen of Happy Volcano. "It's kinda always been like this, but so much more important as nobody takes any risks anymore. All hail the [algorithm]."

We're just getting started with State of Indie Games 2025! Click here for Part 2, the other half of this opus of industry reflection, when our contributors get into topics like funding their games, development tools, and so much more!