The Subtle Art of World Building

How developers build the worlds we play and why it matters

I'm usually not one to build worlds. I like my stories to be character-focused, meandering and expository, thoughtful and dramatic, and sometimes entirely encapsulated in the emotionally fraudulent or sincerely effusive head of a single person.

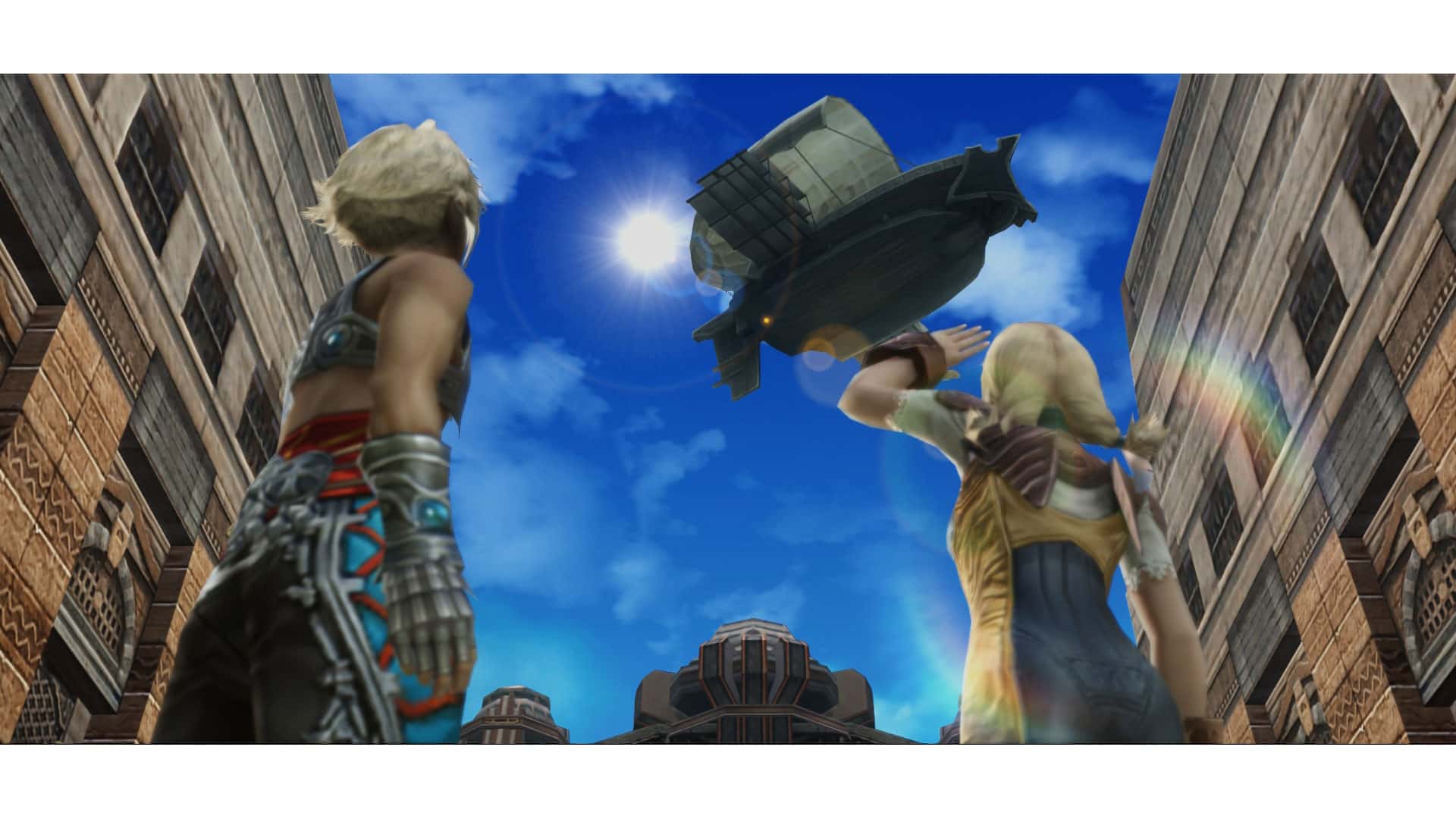

Lore was never my thing--I found the prospect of building a world daunting, especially in high fantasy, where rules and creatures and the politics of a mostly unseen background would always feel like things I'd never entirely be able to enjoy making. But when I played Final Fantasy XII the inverse became true, and there was a nexus where I understood what I'd been missing for years: I did love building worlds, I just wasn't always aware of the many intricacies my worlds did or didn't have to contain. It wasn't always rules and guidebooks, it was tone and atmosphere, opportunity and chance, the details often left best to the audience's imagination.

Final Fantasy XII was the first Final Fantasy story I truly connected with on a grand scale, and I loved the world for all of its deeper unknowns. The game's myriad landscapes - from the dark verdancy of the Golmore Jungle to the seasonal transitions that transform the Giza Plains, bring to life a swashbuckling adventure. I adored the art, which felt mature and inspired, shaded with the softest of brush strokes, while its often muted colors still conveyed a beautifully painted world. I roamed my way across the yellowed pages of its maps to reclaim a kingdom, but along the way, I discovered secret forests, hidden treasures, and dangerous monsters that helped me better appreciate the depth and diversity of this created world's bounty.

Build It and They Will Come...

Worldbuilding, especially in regard to speculative fiction, but definitely in literary or realistic fiction as well, is a storyteller's great immersive gift to readers. The characters and machinations of the plot all exist within this carefully curated space, whether it be a galaxy-wide adventure story or an intimate exploration of family in a rural Mississippi town. A world must be built from the ground up to fulfill more than background appeasement, it must enhance and act as a character itself. In recently reading through The Little Friend by Donna Tartt, the key to making a breezy, summer-lull childhood feel punchy and slightly caustic is in the curation of the parts of the world, and the words, the author chooses to utilize.

The humid, dim summer evenings and chlorine-bleached days are fully realized and meticulously detailed in The Little Friend, lending an air of loneliness that permeates all of Tartt's fiction. It successfully takes the mundanity of rural life and fills it with characters, actions, locales, and incidents that help to form its insular aesthetic: the childhood of this particular grieving girl. While the methodology differs, games do much the same, albeit with a different subset of tools, some of which overlap: in games, the world is modular, visual, and interactive. Whereas books and movies follow a purposeful (and philosophically integrated) linearity, games guide players through crafted worlds that are just as carefully (or flippantly) aware of the permanence of choice. Games are given the opportunity to build stories around players, tucking lore into side content and wayward details that reward curiosity and exploration but are not always essential to the overarching plot.

In all media, there's a method to world-building that can accomplish a great deal of movement with many shifting pieces that must be carefully placed or the whole thing might feel precipitous in execution; I call it "bread-crumbing." Loathe as I am to dismiss info-dumping, as it can be fairly essential; there is an art to carefully placing the parts of a world around its story. Movies like Mad Max: Fury Road do this resplendently well. Through a sparse script, it allows the verbosity of its narrative to be entirely captured in the movie's physicality--the outlandish chases scenes, the garish characters, the shots of the world's inhabitants and landscapes that are never fully explored but are delivered, piecemeal, in a fine tasting of its dystopia. Linear media must use this sparingly but in games, this can be judiciously exploited. With a world so big and so robust, there is no limit to the side quests or NPC events that can give weight to not just the player character, but the character of the world itself.

This open-ended design of games also allows the climate of the world to be actively "alive", inserting immersive moments and filling the landscape with quests, crafting materials, and other side or main options that put the player in full control of the story or, at least, this particular section of it. The execution of narrative is modified--or entirely composed of--player actions; in games that allow a more leisurely exploration, or that forego straightforward "narrative" experiences, the concept of "building worlds" can be less thematically linked to the story and more freeform.

The Wild, Wild Neighborhood

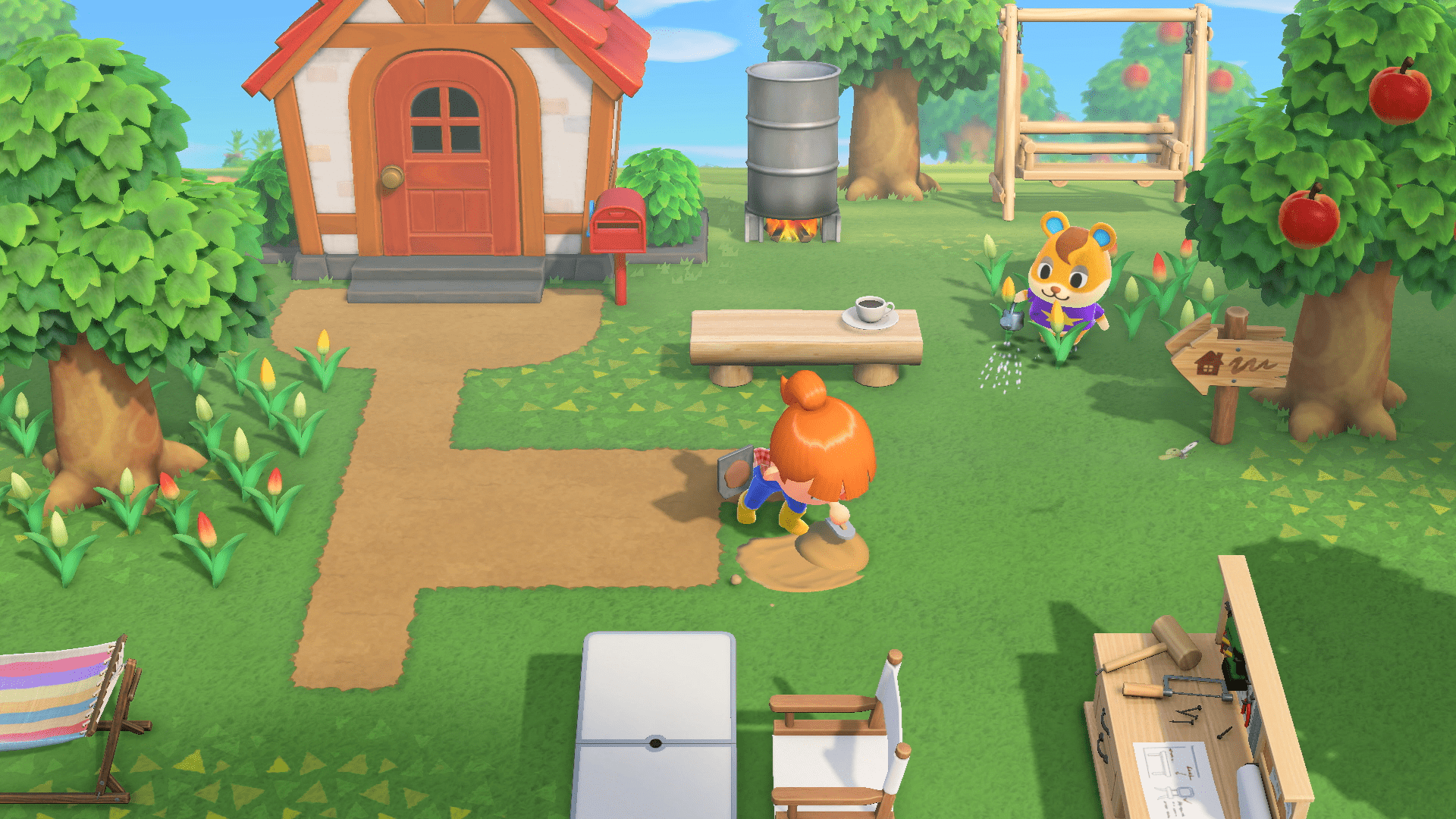

Animal Crossing: New Horizons was a certified hit when it was released in 2020. Coming onto the scene at the height of a worldwide pandemic and unprecedented (but necessary) measures of isolation, it offered a visage of hope and normalcy. In Animal Crossing, fans and newcomers alike could partake in the idyllic work of island-building, curating an experience of organized joy and an almost zen-like daily routine or collecting, fishing, gathering, building, designing, and chatting with occasionally dramatic neighbors.

The story of games like Animal Crossing has always been a strictly foundational one: it allows the player to build the experience themselves. There is a "vibe" to the game that constitutes its world-building, from the art of the characters to the way that the game design itself is implemented. It is populated with NPCs that serve as player companions to help offer them an immersive, fulfilling life there, and the customizable island grants players great creative freedom.

Minecraft and Sims follow in similar veins--but these are worlds largely reserved as "sandboxes", or games that give full player autonomy with little guiding input from the design itself, aside from the limitations it chooses to set. But at its core, the design of the world of Animal Crossing is still intrinsic to the game itself, just as how the recognizability of Minecraft and Sims lends them a certain "feeling." Without the landlord-like Tom Nook, or the museum curator in the form of a cute, bowtie-clad owl, the endearing essence of Animal Crossing would be lost. Its world is one of freedom and personable theatrics, with the story being one that could be made entirely from the building blocks of its built world. Games such as Skyrim or Dragon Age feature a similar concept but are far more traditionally built fantasy worlds, with images and tenants of the genre baked into their DNA. While open-ended, the games vary wildly in tone and offer a more linear pursuit of the story.

There are many games that carry a very particular "feeling": gothic media has historically (and in modernity) featured topics that tend to incite dread or a sense of loss of control, a portending of doom and death. Their settings loom large. Games like Castlevania and other Metroidvania games mimic this setting. Many open-world RPGs tip their hats to the fantasy genre, where the wonder of seeing gargantuan and larger-than-life flora, fauna, and architecture can be rendered in cutting-edge graphical fidelity. Cyberpunk as a concept, while having roots in a fear of globalization and technological advancement, is also a byproduct of noir films, which in and of themselves carry a particularly gritty style, often featuring downtrodden characters clutching the brims of their hats to keep the incessant city rain at bay. It fits more pessimistic (or punk-edged) sci-fi tales, such as the eponymous Cyberpunk 2077, perfectly.

Caught a Vibe

Atmosphere doesn't necessarily have to be justified by the world but by the intent within it: Persona 5 is a wickedly slick urban fantasy RPG held together by the highly stylized world, down to the aesthetics of the pause menu, but its simpler story could take place in any other atmosphere. And yet it doesn't--the gameplay and pace all lend a calm, smirking assuredness that elevates it above its singular, ragtag-punk adventure into a rebellious celebration of maximalism. The recently released Hi-Fi Rush accomplishes much the same--a story of anti-capitalism is expounded by a colorful, musically vibrant world with a focus on explosive action and comedic banter between larger-than-life characters. It's often explicitly on the nose in its messaging, and the world is built to adhere to those ideas: the villains are stock, the dialogue is knowingly B-movie, but by leaning into the sincerity of this it succeeds to convince the audience of its world.

In creating games, atmosphere and the ways in which the player can interact with the world speaks volumes of the intent and creative thoughts behind it. The beloved Resident Evil 4 is memorable in part because Leon S. Kennedy is so gosh-darned, lovably quippy, having a Brendan-Fraser-in-the-Mummy-esque attitude to the game's more overt seriousness. Sure, the world is being threatened by a terrible zombie virus, but Leon's still making fun of the villains and we, as the players, learn to lighten up by proxy. It is still a terrifying game, with villains that devolve into grotesqueries and monsters that breathe heavily in damp, ice-cold hallways, lurking around every corner. It is this juxtaposition that allows it to succeed: Leon's bravery counters our inherent fear, and this is embedded in the world's vision for itself and its gameplay.

When crafting a game or a story, the world-- not just the lore, but the tone--can help define the characters and their dilemmas, even if those archetypes or conflicts already exist. Plopping a heist into a fantasy (ala Vox Machina) or a murder mystery into space (ala Leviathan's Wake) blend compelling visions around each other, often employing the power and faults of both genres and design concepts to great effect. Disco Elysium's heavy narrative is threaded with moments of outright hilarity--from the expounding of the various voices in our head to the background observations of the city's grit and history, the world as narrated by us can feel slightly (albeit purposefully) disjointed by the serious tone and almost gentle nihilism of the game itself. This is world-building at its finest: where tonality in games is played sincerely, and where players are allowed the freedom to further explore this integrated world, in order to better unbox all of its lingering pieces.

Final Thoughts

My first foray into the concept of world-building in games all started with Final Fantasy XII because of its earnest and quiet solemnity, but I had known games in previous years that had expressly developed worlds. At the time, I simply didn't consider them as "literary" or otherwise elevated in the way that I found Final Fantasy XII. In the years since, I've come to view those beloved games through a more similar lens, loving them for the genius I wasn't always aware of at the time. Final Fantasy XII is sincere in its pursuit of narrative authenticity, although it was often dismissed as lacking both the charm of the previous entries' slightly jarring dialogue and often whimsical melodrama, replacing it instead with a self-serious saga and more realistic character designs.

Final Fantasy XII felt expressly like the formulaic, if winning, recipe that made Star Wars successful, in that it was committed to its own original vision of a blended world. Its areas felt full, and the art and very design of the game's numerous, stumbled-upon mysteries made for a fascinating adventure. This is something 2023's Forspoken was largely derided for lacking - it isn't that its ideas of urbanity and fantasy can't coexist, but rather that the main character was often lamenting the existence of that duality. This only served to dull its impact as an atmosphere, which is something explored with greater depth and thought in Post-Cringe: Forspoken and the Self-Sabotage of the Smirking Protagonist.

As the medium continues to evolve, we'll no doubt see new, emerging voices creating games with particular senses of style, hopefully with an assurance of self and a deep understanding of the various layers of designing a world. We play games often to experience a world far from our own or experience a copy of our world in which we're capable of doing the impossible. We play to know farther emotions and lives. The worlds we inhabit tend to inhabit us, and it's the designs behind these games and the visions of their creators--the histories, loves, and passions that drove them--that welcome us to enjoy their visions.