Vacationing With the Paranormal: Exploring The Artistic Direction of The Medium

A look into the duality and artistic inspiration behind the psychological horror game, The Medium

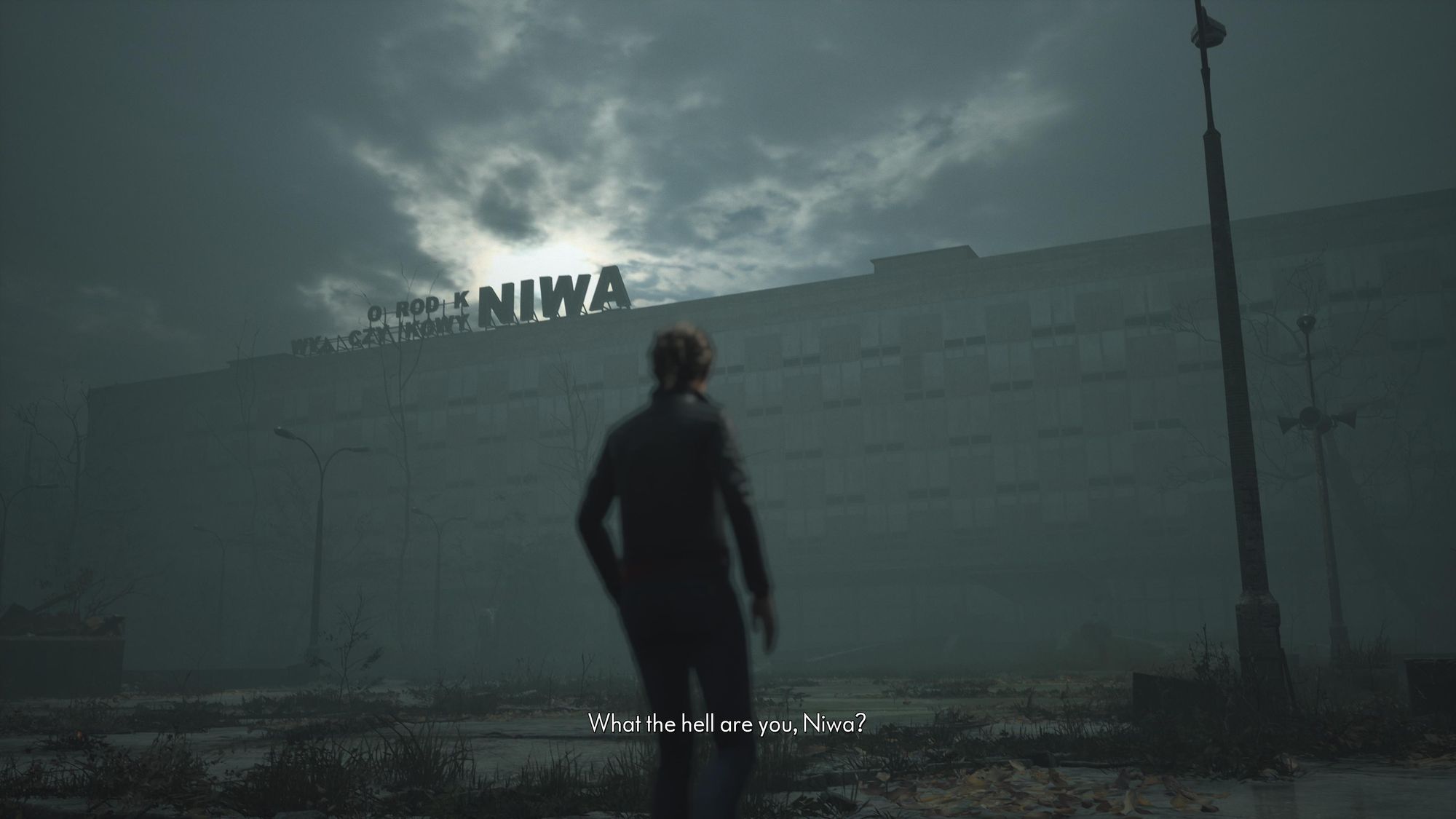

The Niwa Worker’s Resort eats and is eaten.

Advertisements and posters line its walls, mold-infested rugs lay across rooms in shades of blues and greens, and furniture sag with time. There are voices that call out, trapped in telephone receivers, shoes, and stuffed animals until they’re plucked. What parts of the resort that have yet to be devoured are few, already stuck in-between its teeth and waiting for the inevitable. This resort — or rather the things confined to the abandoned resort — still hungers. So when Marianne enters the resort in response to a strange phone call, it is no surprise that these hungry entities will do all they can to keep their future meal from leaving.

Checking In, Party of Two

The Medium is a psychological horror game that had me hooked the moment the opening credits cued up. Our protagonist’s theme swells into existence as black-and-white clips of Kraków, Poland jump cut across the screen. Synthetic, sinister, and somber — the sound suddenly becomes busy as snippets of children at play, medical equipment, experiments, and vials interrupt images of the city. Lightness and unease adjacent on screen, already setting the tone for this game and its world.

There is a duality that is soaked within the world, mechanics, and characters in The Medium’s universe. It’s a recognizable world juxtaposed with what we may fail to recognize — or perhaps wish to ignore – that is visually inspired by the late Polish artist, Zdzislaw Beksiński.

A Period of Transition

Medium's developers, Bloober Team, introduces players to this duality by taking us to post-Communist Poland in 1999. While it’s been about a decade since the end of communism within the country, its buildings featured in-game continue to hold its echo. A news article touting future stability in Eastern Europe is just a room away from a wall recording participation in Poland’s Solidarity movement in the 1980s — a quiet reminder of defiance against authoritarianism. The Kraków-based team shares with players a Polish tale, using this transition period within Polish history as the backdrop.

The Niwa Worker’s Resort, a government-funded hotel designed to embody and provide “socialist joy and recreation,” serves as the lingering echo of communist Poland and the game’s ground zero. Tragic events have cut short the resort's plans to bring “joy”, transforming the building into a stagnate, rotting grave. It’s a space — a moment in history — refusing to be forgotten, still lingering in the present.

Niwa Resort's design was based on the Hotel Cracovia, a modernist hotel from the 1960s that aimed to hide the bleak realities of communism. This is where the game's duality begins to truly reveal itself – the artificial and the reality.

Despite the Worker’s Resort’s claims that its lavish decor and many rooms were intended for the ordinary citizens of communist Poland, I remain skeptical of this claim. Hotel Cracovia and Niwa both give the impression that they were a luxury that few could afford, with only those high up in the Party or foreigners being able to enjoy. There are hints and implications of the presence of high-profile guests such as Boris, who is allegedly the “nephew” to someone important, and stars such as the ballet dancer Vivienne, but nothing is stated explicitly. Despite its original elegance and flourish, what continues to stand the test of time is the hurt, terror, and censorship filling the resort.

No matter where you twist and turn, the eyes and ears once belonging to the Communist government hound (pun absolutely intended) these halls — and still do, in a sense. They forever whisper through dead telephone receivers and linger through leftover police fencing.

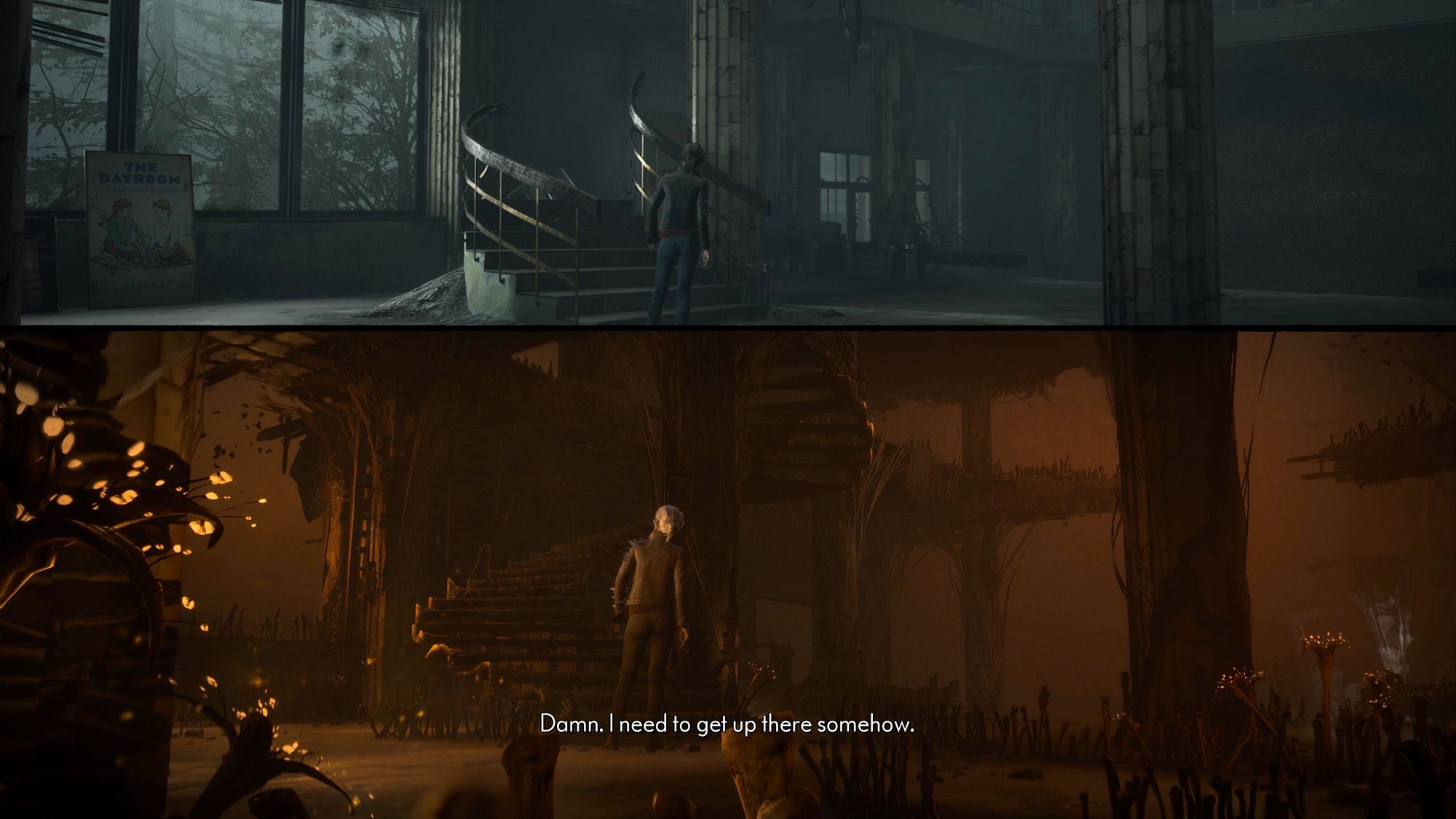

Dual Reality

The protagonist of the game, Marianne, possesses the rare gift of being a medium, with the power to communicate with the dead and navigate between the living and spirit world. The transition between these realms is not a graceful one, often causing Marianne to split violently into two, resulting in a split-screen effect for players. On one side, we see Marianne in the familiar world we recognize, while on the other there holds semblances of familiarity, but is warped and surreal. This jarring change can be uncomfortable, leaving players unsure of which screen to focus on, much like how Marianne must feel when the split occurs, forced to navigate between two starkly distinct realities.

"So there I was, existing in two worlds, but not really living in either."

What’s incredibly clever about this mechanic is that Marianne’s journey can become restrictive or more accessible, depending on these two realities. A door locked in the world of the living may become accessible in the spirit world by having an ‘out of body’ experience. This allows Marianne’s spirit to pass through certain spaces, but it comes at incredible risk. Stay too long outside of your body and watch your spirit become consumed by nothingness. Or become easy prey for one of the unearthly foes that stalks the resort.

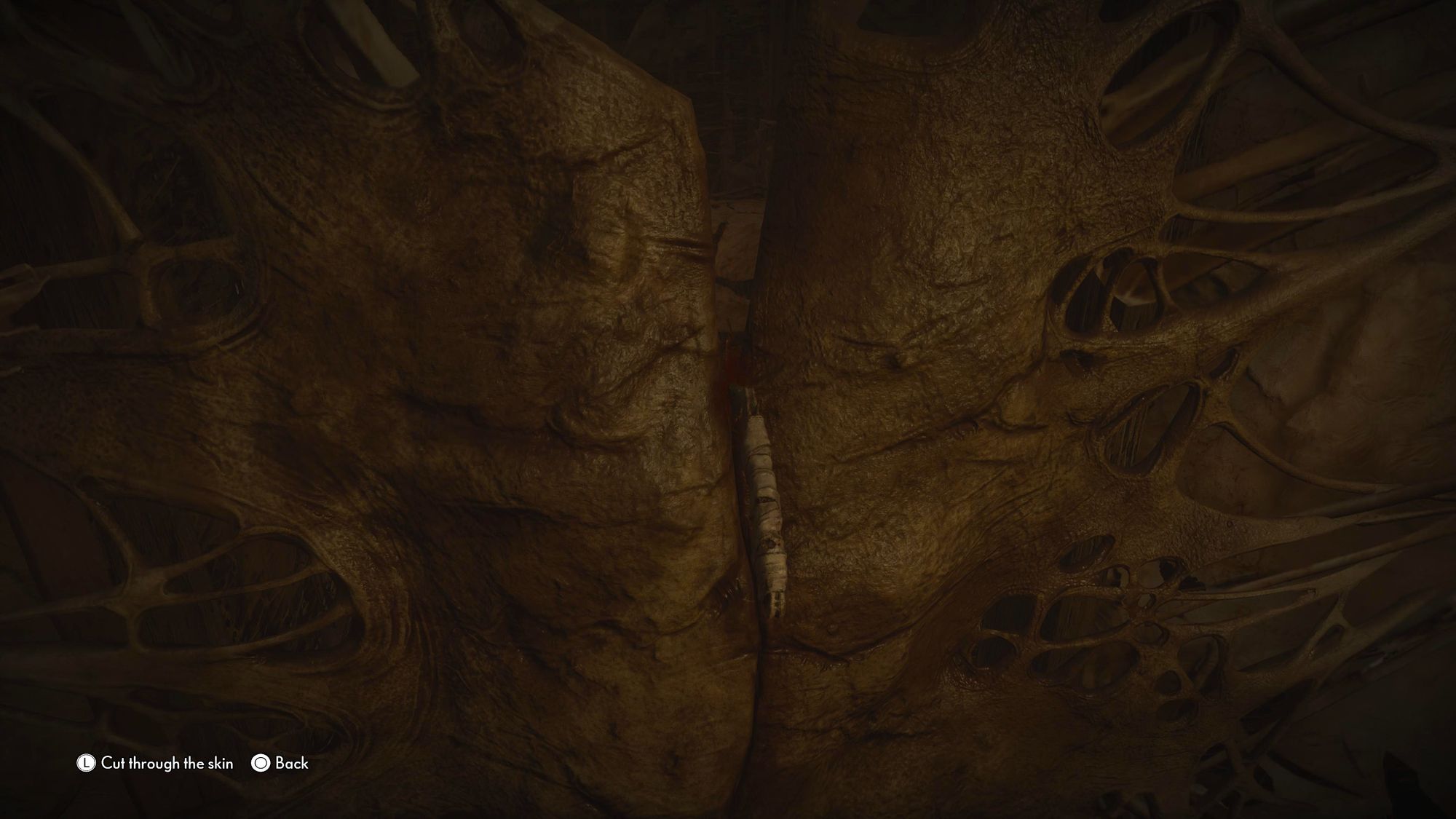

Perhaps there is a barrier in the spirit world making the way forward uncertain. These spiritual barriers often come as a flurry of moths that eat away at you or stretched out skin — yes, skin. Using a spirit shield will zap away the moths and wielding a razor crafted out of shame will cut a path forward. It’s a gruesome and creative mechanic, developers utilizing the PS5’s DualSense controller to the fullest in making you feel the resistance between blade and flesh.

The duality present in The Medium extends to its soundtrack as well, which was co-composed by two renowned composers, Arkadiusz Reikowski and Akira Yamaoka. Reikowski was responsible for the music and audio in the material world, while Yamaoka handled the spirit world. Despite their distinct styles, their contributions blend seamlessly to create a cohesive soundtrack that complements the game's split world.

Yamaoka, who has previously composed music for numerous Silent Hill games, brings his expertise in creating eerie and unsettling soundscapes to the table. Meanwhile, Reikowski, known for his work on Blair Witch and Layers of Fear, adds his own flair to the material world's music and sound design. The result is a haunting and immersive soundtrack that heightens the game's design choices and atmosphere.

The Artistic Inspiration

Where the game visually shines is within the spirit realm. I absolutely love when games plunge you into parallel planes, showcasing a mystifying version of reality. I fell in love with this concept when highlighted in DmC: Devil May Cry (2013) and I’m thrilled to see it implemented to the fullest in The Medium.

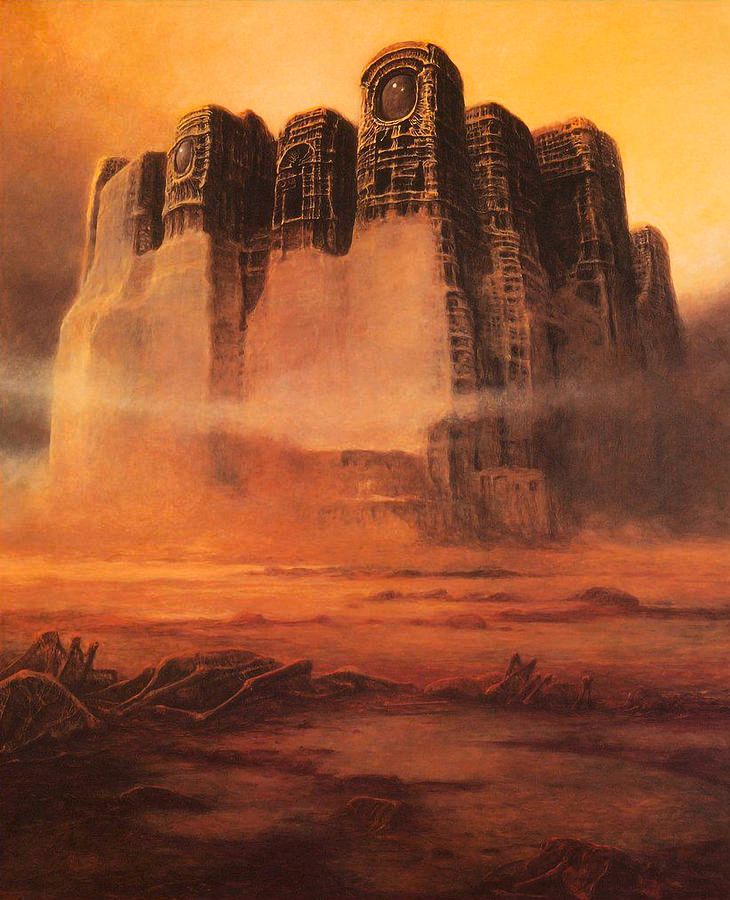

Developers credit the late Polish artist Zdzisław Beksiński (1929 - 2005) as the inspiration for this otherworldly realm. Beksiński is renowned for his surreal and dystopian imagery, but even those categories alone is one the artist would have balked at, stating in a 1997 interview that, “… all I have in common with the surrealists is this oneiric method of creativity.” Regardless, dark and dystopian themes have often been associated Beksiński’s artworks, which are clearly depicted in The Medium, presenting otherworldly beings in bleak landscapes.

Despite the grim imagery in his paintings, Beksiński often insisted he wasn’t trying to convey any message or meaning. He viewed himself as an artist who created works for their own sake and nothing more. Across interviews, you can catch Beksiński scoffing at art critics and viewers who would ponder and hypothesize over the potential symbolism behind specific images (or collection of images) or the underlying meaning behind a specific color palette. This may be why many of his artwork is without titles. To him, when he creates, "simple associations appear", creating content, but in no way does the content hold a specific intent.

Then there are moments in his artwork where there are no clear associations to be found. For example, when an interviewer analyzed his untitled piece of wolves and a hot-air balloon with the term 'NEVERMORE' on its surface, the interviewer discussed the potential connection with the infamous Edgar Allan Poe poem. Beksiński quickly dismissed the notion, sharing he only aimed to present “an interaction of elements that would never happen in reality" and nothing more.

"Something the wolves have seen once and will never see again. [...] You have to feel it. If you don't, then it makes no sense." - Beksiński, 1997.

It’s clear the Bloober Team were heavily inspired by Beksiński’s poignant portfolio, but I’d argue that the team took extra strides to capture the “feel[ing]” that the artist once spoke of and exists within his works.

For example, there is a clear distinction in mood when traversing the Niwa Resort’s lobby and its upper level rooms in spirit form. While the lobby is cast in sepia tones and luminescent fungi, there is an emptiness. The space feels hollowed out and aged. However, when exploring the upper level rooms above the pool, the space takes on a murky, gray hue. Despite Marianne being the only one in these rooms, the space feels oppressive and alive. Mummified figures and death masks are one with the walls, their screams preserved and on loop. Hands dangle from the ceiling, only serving to make Marianne feel closed-in and small. It's within these levels is there more sound, mood, and atmosphere than an underlying message being conveyed – all of it working together to preserve the mystery that is the Niwa Resort.

My favorite levels, however, were the ones that dived into the human subconscious — that are rife with intention and smothered memories, giving a nod to Beksiński abstract and surrealist art style. This uncomfortable peeling of private stories and festering guilt can only be accessed by another medium named Thomas, the game's deuteragonist. Without revealing too much, Thomas has the ability to invade another’s subconscious when physical contact is made.

I can’t get over how grotesque and slimy the headspace is for a character revealed to be a child predator. The bile-tinged world is littered with bones, murky standing water, tendrils, and elongated hands with boils. In the middle of the space stands a house infested, oozing a dark liquid defined as loss, hatred, and grief. Here players listen to scattered memories held within items, faded portraits, and doorways — snapshots of said character as a young boy living in occupied Poland during World War II. Developers utilized the environment to masterfully show a loss of a parental figure, Polish Jews who went into hiding and relied on others to help, and the horrifying aftermath when one collaborates with the Nazi Party. The game in no way attempts to garner sympathy for this character, but rather explores how traumatic events can create demonic entities — how trauma can become cancerous to the mind. It’s fitting that the final confrontation scene sits within a landscape inspired by Beksiński — the imagery caught somewhere between infestation and decay.

Another unique world presented to players is that of a red-tinged workspace existing within the mind of a Security Service agent during communist-ruled Poland. It's a sharp contrast to the greenish hellscape previously explored. Developers filled the area with filing cabinets bulging with documents that tower and sag under their weight, as well as interrogation rooms and televisions squeezed into the densely packed space. You can hear the distant sound of a typewriter, as reports are filed and enemies to the communist government (or to the agent himself) are sent off to face punishment.

This level happens to be my favorite, sound masterfully used to signify shifts in the story and visuals. For example, a fluid audio transition will take place as the pathway made of the spines of shelves is replaced with tile. Players are transported to a butcher shop, a rations card sitting by its entrance. The clacking of the typewriter becomes replaced with the squealing of pigs and the thudding of a cleaver. Towering shelves are replaced with walls of hanging pigs. The game developers make subtle references to the challenging circumstances Poles encountered when purchasing essential items while under communist rule, particularly meat products, as ration cards were limited during that time. The flashlight that peeks and seeks you out through the walls of dripping pigs carries the accusatory tone felt across this headspace.

Although there is no specific Beksiński painting that this space directly embodies, I'd argue there are several paintings that align with the artistic direction taken — a character dwarfed by looming entities, unearthly architecture, and pockmarked columns. In no way do I feel the heavy leaning on red is a reference to communism, but rather the perpetuation of a feeling of hostility. My mind even found itself wandering toward Bloober Team’s Layers of Fear 2 where sections of the game are completely drenched in a deep red hue to assist in creating an uneasy atmosphere.

Whether the Niwa Resort has had its fill remains ambiguous, even when the credits roll. As for me, I still cannot get enough of this haunted resort.

From the eerie depths of the abandoned resort to the red punishing haze of one’s mind, the game’s hunger for more is contagious. The decision to find inspiration from Zdzisław Beksiński’s thought-provoking and twisted paintings helps to create a unique and novel landscape while paying homage to Polish history. What I deeply enjoy is the dual nature of the artistic direction: connecting to Beksiński’s works and methods — crafting a feeling versus an overt message, and levels in which art serves as an expression of the human psyche or as a footprint of the experiences of many.

The use of artwork extends even beyond the visual, with the game’s soundtrack featuring Arkadiusz Reikowski and Akira Yamaoka. The collaboration between the two brought two unique musical styles and two worlds to life through the game’s musical scores and soundscapes. Here music acts as a way to amplify the visuals, a way of sharpening even further the teeth of the dangerous entities that walk its halls and intensifying the pain that coats its walls like a bruise. Just like the resort itself, art in no way is a passive element in The Medium, but an active force that shapes the game’s aesthetic and thematic identity.

I highly recommend visiting the Niwa Resort, but best of luck when it comes to checking out.