Death Stranding 2: Should We Have Connected?

I will hold you and protect you

I hate being on the other side of an amazing video game.

That thing that I anticipated, that I yearned for, that I loved playing—it's all behind me now. The action of enjoyment cannot be replicated; the innocence of the unknown has been spoiled in my favor, and I cannot experience it for the first time again. There was a world in which I'd never played Death Stranding 2, had only dreamed of what it could be, of how its story could unfold after the first; now there is a world after, and I am at fault for these actions, because I can only sit with myself and remember.

Death Stranding is a game about connections. It's about loneliness, isolation, and bridging the impossible gap between the self and the other. Where Death Stranding is about uniting strangers, its sequel is about building stronger relationships with the familiar. It remains a game about traversal, meditation, and small accomplishments, but now we are treading new and old ground, with personal agendas hardening our mission.

"To live is to imagine ourselves in the future, and there we inevitably arrive. Yet our place in said future may not be the one we envision."

Kōbō Abe

In Woodkid's track "To the Wilder," he says: "But if you doubt and question what the future holds, remember there's no place you can't call home." Death Stranding 2 isn't just about finding a material home, but about preparing ourselves for an uncertain future and imagining a place of belonging. It's a game about the iron strength of camaraderie, and how deepening our connections with others is the only true way to be human.

When you surround yourself with friends, you are never really alone.

Sticks and Ropes

I've been obsessed with Death Stranding for years now. Long before the original in 2019, I was enraptured by Kojima's teases of a game that seemingly defied genre and explanation. Now, having played both titles, the mystery is lessened—Death Stranding still upholds its strangeness. Still, the knowing is there, and my limited observation leaves me with an artistic experience that I can comprehend, if just barely.

In my other writings about Death Stranding, I explored the title's unrelenting optimism. Kojima was inspired by Kōbō Abe's concept of "sticks" and "ropes," the first tools of mankind, where one was meant to keep others at bay, and one was meant to bring others toward us. Death Stranding is a "rope" game, where the use of harmful tools is generally punished in catastrophic ways.

Kojima tends to be prophetic. This comes from his being an avid student of history. He and his team can replicate cycles in their stories, which is why Death Stranding feels like a quintessential Covid game—its themes and concepts of separation and delivery in the face of such catastrophe emulate real-world events to a shocking degree.

Death Stranding 2 leans into the stick. Our ropes are still in place, and Sam must again unite a portion of the world via an advanced iteration of the internet, forging connections that allow both physical and digital interactions to flourish in a post-Stranding world. This time around, weapons and machines are delivered at a much faster rate, with the player having access to specific weaponry that helps fight off BTs, humans, and mysterious Ghost Mechs. While still largely meditative, Death Stranding 2 feels far less lonely than its predecessor. We have the sticks on our side, and we are ready to use them.

The Man Who Delivers

I am having a difficult time fully articulating Death Stranding 2. The game wears its merits on its sleeve and deserves to be a contender for Game of the Year. It may well be the most beautiful game I've ever played, with graphics that far exceed those of its contemporaries. Many of the environments are so realistic that it's difficult to believe they are graphics at all, and not some sort of photographic trick. It's obvious that the team spent a lot of time observing these locations, especially Australia, where the game attempts to replicate the realism of this country, rich in diverse biomes. Death Stranding's "America" was infamously designed after Iceland, and Sam Porter Bridges travels across moss-laden footpaths, dewy hillsides, and rivers that snake through cloistered copses.

"In our small, careful way, we have changed the world, and what's left for the players is to take a victory lap, to reflect on the strands that unite us."

Death Stranding 2 makes you feel like you're there. I've never visited Australia, and even if liberties are taken, there is an artistic application to the landscape that felt even more realistic than Death Stranding's believable landscape of wetlands and mountains. Between Mexico and Australia, the limn design of these real-world places still bears the beauty of the artist. In too many modern games, the desire for realism comes across as flat and uninspiring, the pursuit of "realism" flattening the creative. In Kojima's verisimilitude beats the heart of the place, redistributed through graphical design.

As with the first game, I'm sad to no longer be in these places, making my deliveries, connecting folks, saving the world. The Sam of the first game is more infamous than the man himself, and the "Man Who Delivers" has become a sensation. In our small, careful way, we have changed the world, and what's left for the players is to take a victory lap, to reflect on the strands that unite us.

Give Up

I don't wish to spoil Death Stranding 2 in any meaningful way. My desire here is not to offer a review, but to try and summarize my post-game feelings. As a writer, I remain frustrated that there is no word in English to describe this specific post-game feeling. Finishing a game does not feel like finishing a movie or a book. It's a unique bit of emotional and physical digestion, putting away this thing that I've spent the last month engaging with day after day. Death Stranding 2 didn't just happen to me—I was a participant in its world.

It makes me want to cry.

In anticipation of Death Stranding 2, I replayed the first one, this time finishing my Director's Cut file. I still wasn't able to accomplish all the new si,e content before the release date, but I essentially played nothing but Death Stranding from April to July this year—that's a lot of deliveries. Ignorant, chronically online folk still label Death Stranding as a "walking simulator," and while it categorically defies that label, it's difficult to describe just how fun it is to walk, climb, and build in these games. There is a great effort in the hikes between deliveries, and even after building ladders, bridges, and highways, the journey between destinations becomes something philosophical and enjoyable.

How many times in my Death Stranding 2 experience did I deliver a package to a new destination as a piece of affecting music began to play out of nowhere, yet another gorgeous track from Low Roar or Woodkid or Magnolian or Gen Hoshino, or Silent Poets? How many times did the melodic, intense tracks of Ludvig Forssell animate story scenes? Walking under a giant moon, traversing a snow-capped mountain, stomping through rivers, carefully moving over craggy peaks, each time an emotional gutpunch of silence punctuated by familiar voices, as I performed my somber task—this is Death Stranding.

It never became repetitive. It never lost its luster. And never once did I give up. Minus sixty-one...

Same As It Ever Was

Death Stranding makes me think of Shadow of the Colossus. Maybe not in the specifics of their design, but in their pensive similarities, how each game feels so wholly intentional it's hard to believe it didn't come into existence fully formed, a tome pulled from the artifice of time. Art, in the form of a game.

I played Shadow of the Colossus for the first time in 2006. It was spring break, and I'd rented it based on its impressive ad campaign. At the time, there was nothing else to compare it to, and the scope of the game alone was enough to pique my interest, not to mention the radical design of the colossi themselves and the mystical, foreboding dark green color scheme.

It wasn't the first game to make me consider that video games were perhaps more than pieces of consumable entertainment, that maybe entertainment was the part of the experience that was holding their greater themes back. I've played many games in my life that I didn't find particularly "fun" to play—they either grew on me, or the experience was so impactful because of music or story that they continue to live in my brain, adding to the Bible of inspiration that I pull on every day.

A video game doesn't have to be fun to be valuable.

Death Stranding 2 is fun. Moreso than the first game, its gameplay loop is tighter, with much of the game feeling like a recreation of Metal Gear Solid V, Kojima's unfairly maligned opus that predated his exit from Konami. Woodkid told Rolling Stone that Hideo Kojima was worried the game was a little too good, that it would not be polarizing enough for players. "...we have been testing the game with players, and the results are too good. They like it too much." Now, after playing Death Stranding 2, which was excellent and immensely entertaining, it makes me wonder how it was before, and what Kojima changed. There is a weirdness in the game that tops even that of the first, but it's nothing that Metal Gear Solid veterans can't handle, and maybe a level of meta that should be expected from artsy Japanese games as a whole.

Perhaps Kojima will find what he's looking for in OD or his other upcoming projects.

“I don't know why people expect art to make sense. They accept the fact that life doesn't make sense.”

David Lynch

Now, not every aspect of Death Stranding 2 is rip-roaring fun, but it's the sum of its parts, and how the game is so cohesive that it begins to feel, again, like nothing else. Though Kojima once touted the "Strand-like" game as a new genre, in the time between releases, we have not seen a slew of indie releases mimicking the specifics of Death Stranding, even if delivery system games are not entirely unique. It's the totality of it, the way that Death Stranding 2 is somehow formulaic (in the way that Souls games are formulaic) and entirely original. Death Stranding and Shadow of the Colossus care far more about the presentation of the experience than your personal interpretation, and American gamers especially are so intensely solipsistic that they demand games cater to them, and not the other way around.

Phantom Pain

Death Stranding might not be for everyone, but whether or not it's your cup of tea, you should be overjoyed that it exists at all.

Yoko Taro recently said on Twitter: “I’ve been a part of the game industry for 30 years, but I feel there’s less ‘weird people’ now. I don’t know if this is something simply happening in my field of view, if the game industry ended up like this, or if the whole world is like this now.”

Kojima Productions feels like a real-world iteration of its creator's own Diamond Dogs mercenary group from Metal Gear Solid V. In a world of AAA games that are beholden to budget changes, oversight, and misappropriated budgets, Kojima Productions is allowed to be fully weird and creative, utilizing the power of their funding to create truly unique pieces of art that do not have equals in this rather strange and frustrating moment of video game history.

It's not uncommon to hear gamers' displeasure with the AAA gaming scene in 2025. Studio fractures, sudden layoffs, poor investments, and trend-chasing lead to games that are shipped glitchy, unfinished, or dead in the water, with millions of dollars and tens of millions of man-hours wasted. This is what makes talking about Death Stranding so frustrating, because it continues to feel like it exists within its own planisphere, taking extraordinary chances in game design, presentation, cutscene length, and the integration of its many disparate parts.

It is not without equal—there are plenty of indie games and indie creators whose originality might even be beyond that of Kojima—but it's the ability to direct an expensive game studio toward a singularity of vision that I'm certain feels mind-boggling at times.

Tomorrow Is In Your Hands

We forget that we matter, sometimes.

I'm not certain it's inherent. I think it's a mechanism of the world we live in, the oppressive nature of society stripping away meaning and treating us as cogs of capitalism. Sometimes, all it takes is a dinner with friends to remind us that we are important in the smallness of our world.

Death Stranding 2 is about our material place. It's a political game; whose politics are deeper and stronger than whatever braying of gamers could demolish with their bad takes and half-cocked essays. It is a symbiotic game; whether it was designed for Covid or not, whether it was written to be emblematic of our current America or not, Death Stranding presented itself as a rallying cry for an audience desperate for meaning in a big-budget game. Sam's "America's finished" line from the first game feels different once we step foot into Mexico and Australia. It's not only an angry, reactionary ideology; it's the truth. Death Stranding 2 showcases the importance of cooperative globalization, a connected world that does not need superpowers and walls.

I've written about Sam's pain before, how Kojima's insistence on putting the world on the shoulders of a deeply traumatized, emotionally disabled man also feels political. I remember back in 2021, during Hurricane Ida, there was a video of a man making deliveries in the depths of the storm, trudging through waist-high water to deliver someone's food. The news painted this man as a hero because who else would make such a silly delivery during a deadly storm? But maybe the framing should have been on the other side of the story—who would order something at the end of the world?

"Maybe Sam does what he does because it's who he is—the man who delivers."

Death Stranding 2 offers a glimpse of a happier, semi-retired Sam, but, being a video game, it's essential to inflict additional trauma on our hero before sending him off on yet another journey. This is where Sam Porter Bridges feels like the everyman, despite his abilities: his actions occur because they are the right thing to do. Is it selflessness? In this world of increasing solipsism, vicious political sides, and a tide of fascism, selflessness feels as rare as an adult cryptobiote. Maybe Sam does what he does because it's who he is—the man who delivers.

Should We Have Connected?

Death Stranding 2: On the Beach has an important tagline, one that crystallized as I neared the end. "Should We Have Connected?" comes across as a question of consequence, a retaliation for our efforts in the first game. While the UCA might have been successful in connecting its threads across America, there are unanswered questions forged by individuals throughout the experience. It is still America, the king of wars, a sovereign nation of imperialism, that caused the Death Stranding. Even before such a calamity, we continue moving into an era where America's usefulness has waned.

Reality versus perceived reality might be the game's most important philosophical value. Sam Porter Bridges is softer here and less alone. Tarman, Dollman, Fragile, Rainy, and eventually Tomorrow join the crew of the DHV Magellen, and the lonely, traumatic feeling of the first game is replaced with something that feels like home. There is always a place to return to, no matter how tough a mission is. We don't have to wait until we get to the next bunker; we can simply return to the ship for a shower and a nap.

Death Stranding and Death Stranding 2 feel like chapters of a whole, their themes and connections paroxysmal as we guide Sam across yet another foreign landscape. The heroic, gamified, fourth-wall truth of it all is that we expect to be rewarded for our efforts, we expect a boss battle, we expect a sewn-up ending, and we are given that. The unknown becomes strangely familiar as we get Death Stranding, even when Kojima unleashes his deeper weirdness. In the depths of these dance-offs and kaiju battles are pieces of a bizarre familiarity, especially for those like me who have been playing Metal Gear Solid for most of their life. The Kojima-fication of fiction is anything but expected, but the perception has changed.

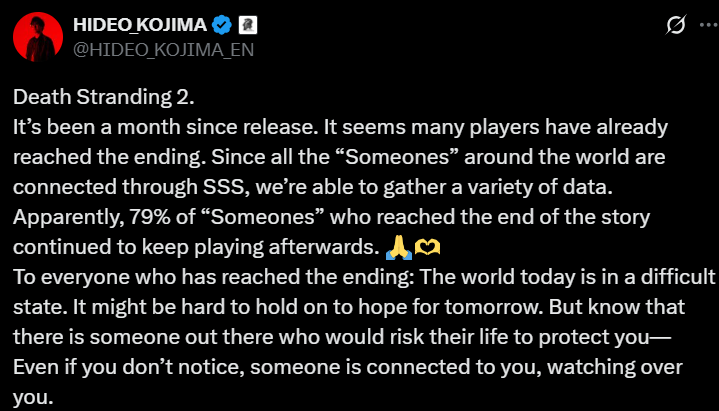

There is a life before and after Death Stranding 2. Over the last few weeks, I've watched social media bloom with newcomers finally giving the first game a chance, undeterred by the lazy bloviations of those afraid of authentic experiences. Maybe that's the real connection, hailing back to the concept of the original. It's not only the material concepts of building zip-lines and freeways, but of acknowledging our fellow enjoyers, and seeing that it's still possible to be creative in an era that's imploding with "stuff."

On the Beach

Death Stranding belongs to a particular family of storytelling where it truly doesn't matter if you understand everything or just a little. It's Twin Peaks, or Silent Hill, or even something more mainstream like Lord of the Rings. After playing Death Stranding twice, am I close to fathoming every painstaking piece of lore? Absolutely not. It's in the depths of the weirdness, tar-logged, fantastical, that story beats emotionally resonate.

It's a micro and macro-methodical climb. It's seeing Sam with Lou. It's the return of friendly faces. Strip Death Stranding down to its atoms, and maybe it's more familiar than you want to believe. But we owe ourselves to the experience, to the totality of a thing, where the flavor is the meaning, and we return again and again with new understandings, to make the pieces fit.

My partner watched me play Death Stranding 2 here and there across my 60-hour trek. They watched the last few hours of the game with me, and even without the scope or context, they cried. That's the emotional resonance. That's what makes Death Stranding so fascinating. It dips into something primal and human, and beyond the memes and the silliness, it's stronger storytelling than we usually get in this medium.

The world wants your weirdness, your creativity. It demands it. Play Death Stranding and realize you are selling yourself short, that you could be truer to your heart, that your tastes are valuable, and should be celebrated.

It might be difficult to continue holding the hands of strangers, or imagining a better world, or even wanting to leave the safety of your home. The value of connections changes over time. Too often, it's our perception that is flawed; you are surrounded by people who love you, and that's a world worth fighting for.