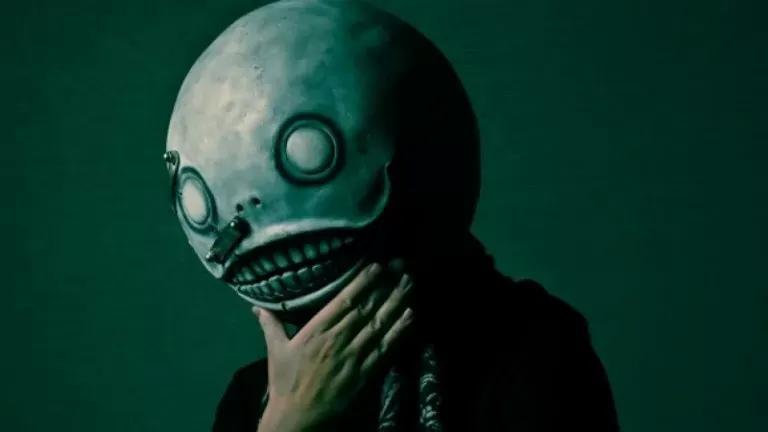

Game Masters: Yoko Taro

How to recognize a Yoko Taro RPG

If we were to define what is more or less recurrent and distinct in the style and/or theme of the works of the main RPG auteurs, what would be the elements to be highlighted? What are the signatures left in the works of the greatest Game Masters of the RPG genre? That is what I will answer in this series, and today, in particular, I will analyze this question in the works of Yoko Taro.

Although there is a long discussion on this subject, and there are very particular contemporary works of art, some of which are made by objects without direct manipulation of the human being, in a classical sense (Hegel’s Aesthetics), art can be understood as an object that has been freely molded by a human being in order to express something to someone. It is in this sense that:

"Art proper, for Hegel, is the sensuous expression or manifestation of free spirit in a medium (such as metal, stone or color) that has been deliberately shaped or worked by human beings into the expression of freedom."

The premise for this series is in the concept of auteur and that video games – as works created by the creative freedom of their developers – can leave signatures of their creators. In my essay Auteur Theory and Videogames (2022), I traced the origins of the concept of ‘auteur’ (fr., “author”) back to cinema and showed how some video game directors (such as Yoko Taro) can be considered auteurs according to three criteria:

- they have their own recognizable style and/or a recurring theme in their career;

- they have a high degree of control over the parties involved in the development of the work; and

- they have autonomy in the general creative process of their work.

Defining an auteur's "signature" is not a simple task, but even more so when he is deeply connected to a single franchise. With Yoko Taro, this is of course the Drakengard/NieR franchise. Taro has not directed or written any games outside of the Drakengard/NieR series, except for the recent two Voice of Cards titles and SINoALICE (2017), as creative director.

- Drakengard (2003) - Director

- NieR (2010) - Director

- Demons' Score (2012) - Co-Director

- Drakengard 3 (2013) - Creative Director

- NieR: Automata (2017) - Director

- SINoALICE (2017) - Original & Creative Director

- NieR: Automata (Become as Gods Edition) (2018) - Director

- NieR Re[in]carnation (2021) - Creative Director

- NieR Replicant ver.1.22474487139... (2021) - Creative Director

- Voice of Cards: The Isle Dragon Roars (2021) - Creative Director

- Voice of Cards: The Forsaken Maiden (2022) - Creative Director

The Recurring Themes in Yoko Taro's RPGs

Nicolas Turcev, in his book The Strange Works of Taro Yoko (2018), emphasizes that "The director's great altruistic project is part of the portrayed opposition between games and nihilism. By creating video games, Taro Yoko is not just experimenting. He wants to save the world." With Drakengard (2003), for example, Turcev noted that, in contrast to the Dynasty Warriors series,

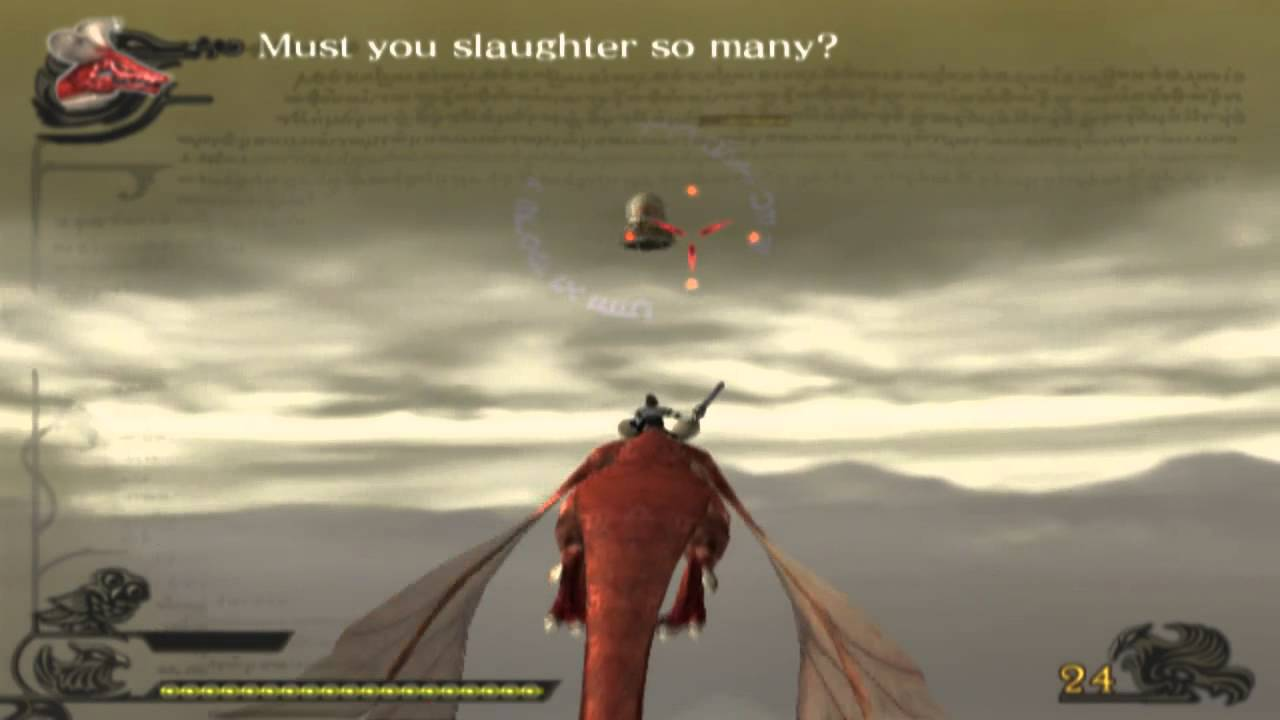

"...the game theme was based on immorality. The strong presence of hack 'n' slash elements would serve as a foundation for this orientation. In Yoko's mind, it was indeed the perfect opportunity to reflect upon the tendency that video game heroes had towards killing without shame, without the slightest trace of moral distress. [...] Surely, Yoko thought, the characters participating in such atrocities must actually go mad and should not deserve a happy ending. Madness thus become the leitmotif of the first Drakengard, whose characters suffered all more or less from insanity, in one form or another; incest, pedophilia, cannibalism, blood lust, the overstatement was intentional and exaggerated, but not totally meaningless — both on the marketing and the artistic levels."

Although with some peculiarities, also in Drakengard 3 (2013), Turcev noticed a repetition of this same message: “there is no other justification for murder than the madness of humans who wage war against each other.” The author also noted that,

"...by failing to place a moral anchor to base this on, Yoko purposely placed the player in the judge's situation and let his own ethical code color the narrative. And unless you were a serial killer or a sadist, Zero's Bloody killing spree could only seem unfair and illegitimate. That was the trick, since this prejudice would later be reversed, when the Intoners would reveal themselves to be emanations of the Flower's power whose existence threatened the world."

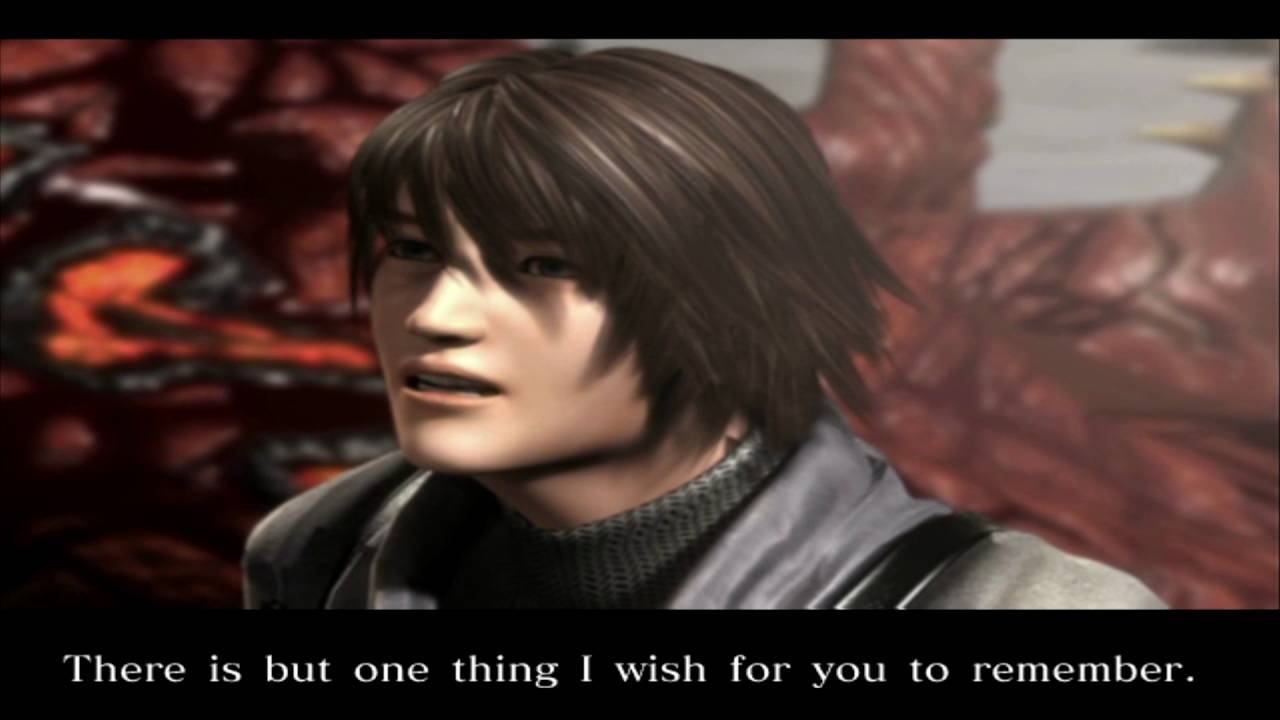

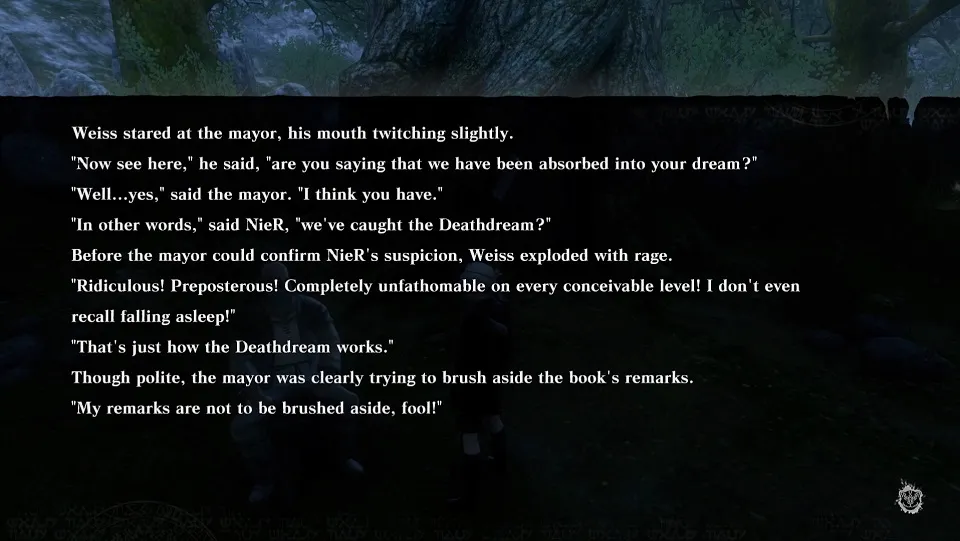

Turcev interprets Drakengard 3's narrative as opposed to that of NieR. Instead of the player starting from a justification, such as a daughter's desire for survival, and then having a revelation that puts their principles in check. In Drakengard 3, the player starts as a villain and waits for a plausible justification for his actions. Thus, although with an opposite approach, NieR (2010) also thematizes altruism, existentialism and morality.

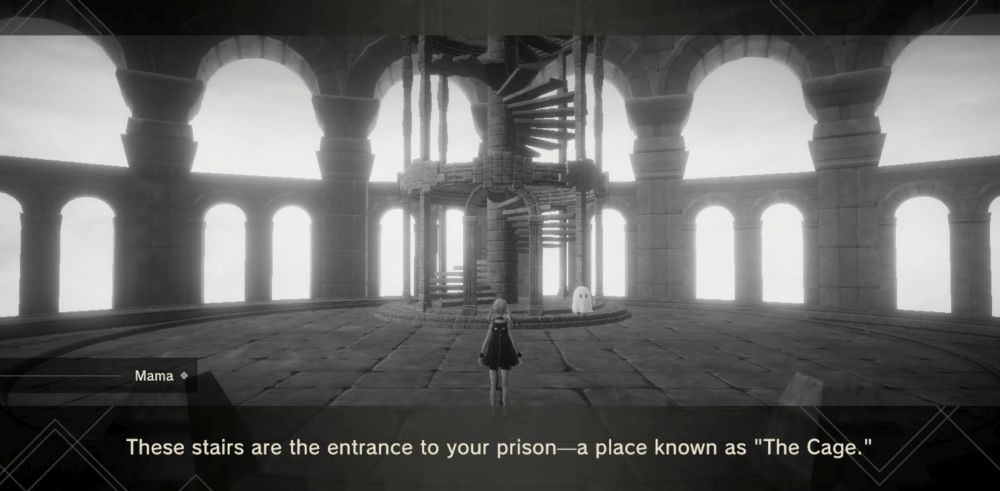

From left to right: Drakengard 3. Source: kako; Nier: Automata. Source: Reset Era.

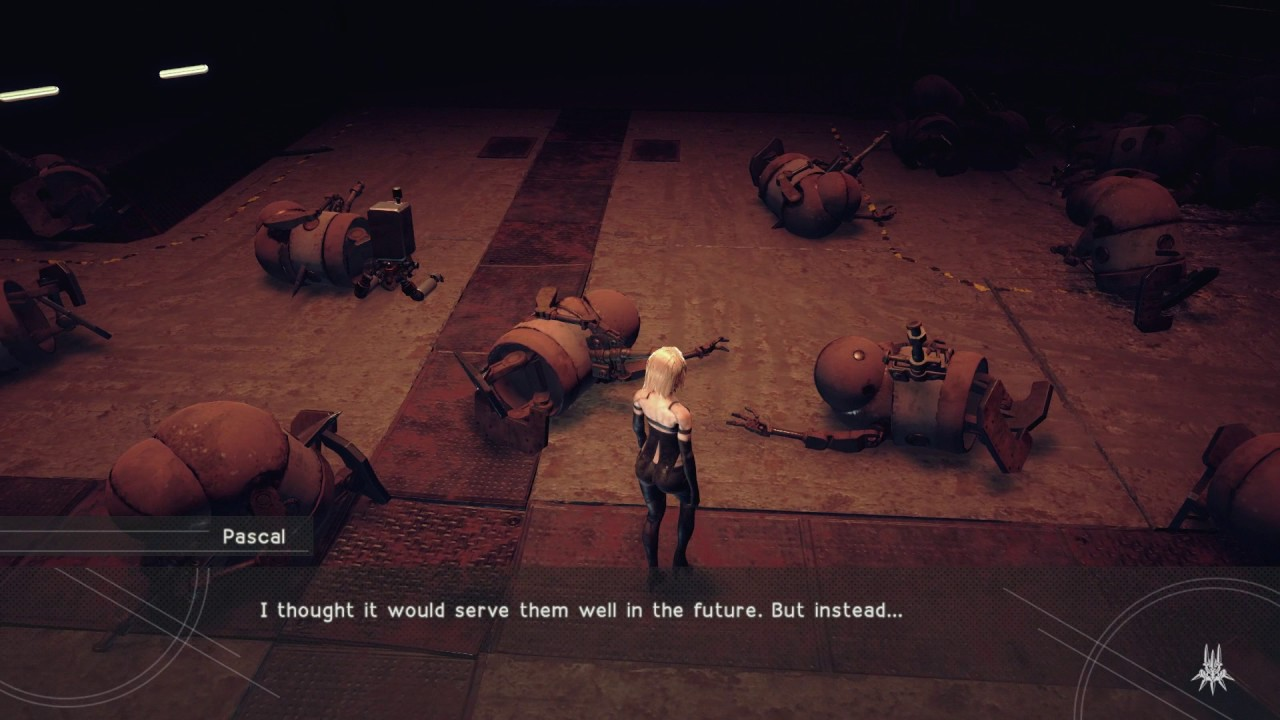

In NieR: Automata (2017) this theme returns. The player’s morality is put in check when he has to follow orders without knowing the fundamentals behind them and face robots with similar behavior to humans. There are also many existentialist reflections in the game’s dialogues and whether altruism is possible is explored both in text and mechanics that break the fourth wall, especially at the end of the game.

Although on a much smaller scale, these themes are also present in the Voice of Cards series. That one of the protagonists of Voice of Cards: The Isle Dragon Roars (2021) is a monster is not random, and the narrative aptly reflects on the nature of these monsters, along with a human side to them. In Voice of Cards: The Forsaken Maiden (2022), there is a less direct approach to the “humanity of creatures”, but there is a more complex narrative that works with existentialism and morality in a deeper and more expressive way.

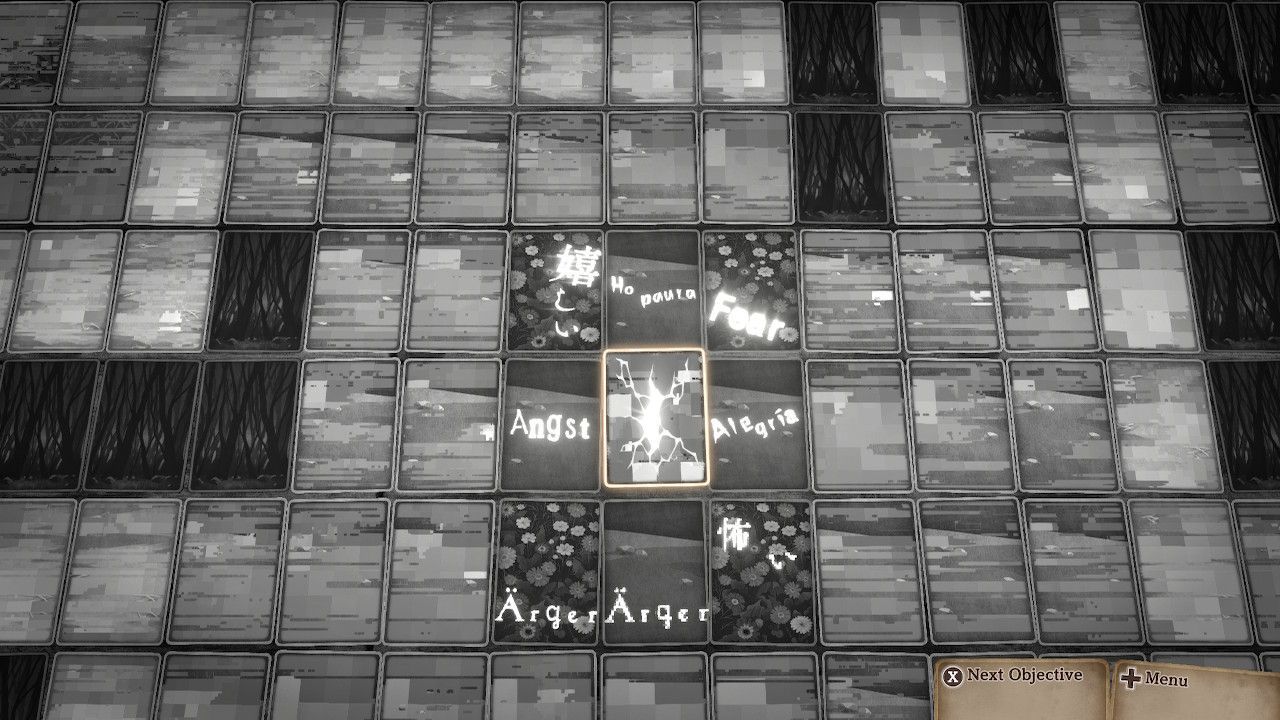

From left to right: NieR: Automata. Source: iparchive; Voice of Cards: The Forsaken Maiden. Source: Author.

This type of theme is present even in the world of SINoALICE (2017). In The Library, a fantasy world filled with countless stories, we witness characters within each story wish to revive its author for the desired future. They work together to gather inochi and fight the story-devouring nightmares, knowing they will inevitably have to kill each other to fulfill their wish.

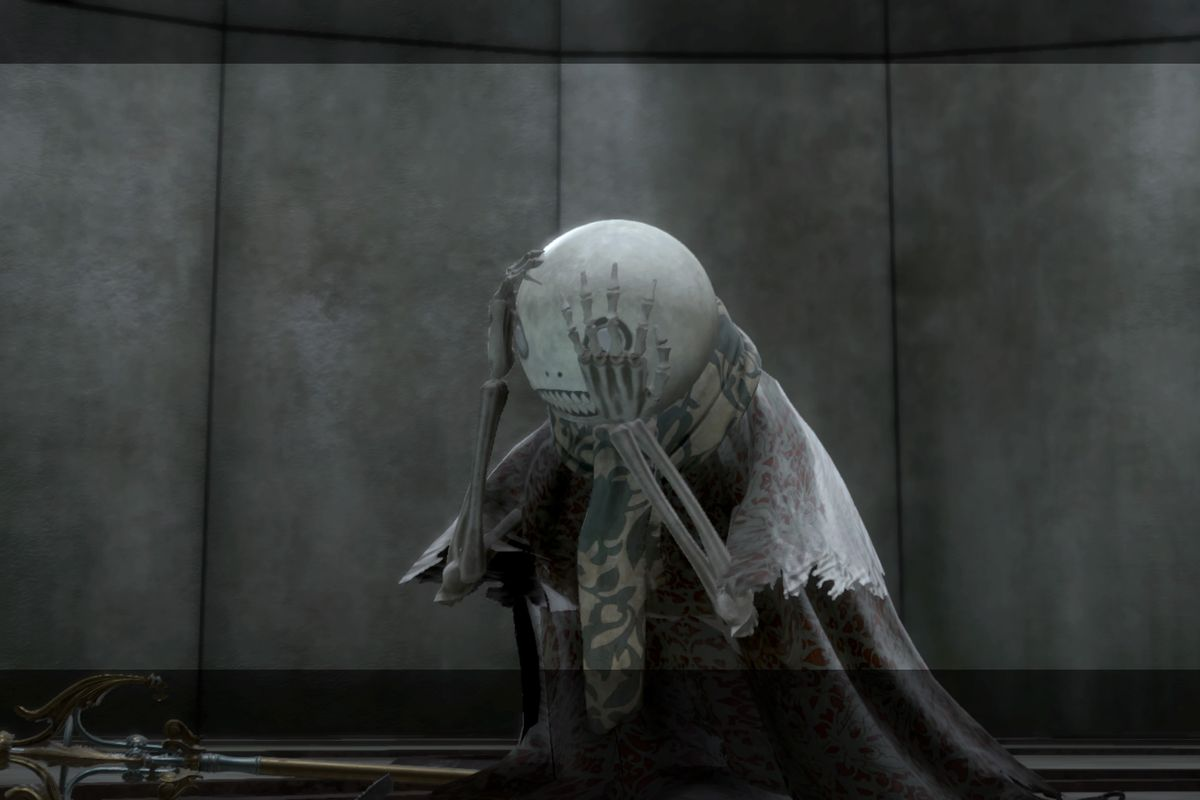

In all cases, Yoko Taro's RPGs reflect on at least one of these three themes: altruism, existentialism and morality. And also in all cases, there is a question about the distinction between creatures vs. characters – which I explained in The Poetics of Narrative Design in Video Games (2021) –, and a denaturalization of creatures as mere "targets" along the journey.

Yoko Taro's Style

In addition to these themes, NieR makes clear two aspects of Yoko Taro's signature, which Turcev calls: "profusion of genres" and "meta-entertainment". Meta-entertainment means using game design to make players reflect on their own gameplay experience. In Yoko Taro's games, this is done by its branching narratives and/or by experimenting with the player's save file, connecting the characters' memories with the player's memories.

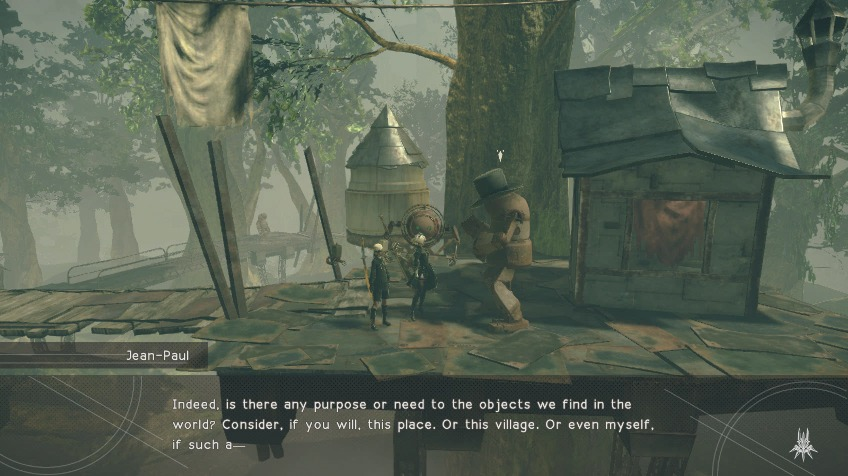

This means that there is a confluence of various game genres, defying the limitations imposed by a single genre. In Drakengard we observe this through the alternation between shooter and Hack ‘n’ Slach moments, for example. However, in the NieR series, it becomes much more clear, the series featuring moments of visual novel, danmaku, platform, and juggling with camera angles. Although this feature is not present in Voice of Cards, it is quite common in Yoko Taro’s works.

From left to right: Drakengard. Source: Sigmanty; NieR. Automata. Source: games.mail; NieR Replicant ver.1.22474487139.... Source: Biggest in Japan.

NieR: Automata is the game in which the public noticed another signature of Yoko Taro: his otaku references (usually seinens). But these references have been around since Drakengard. The most obvious references are in relation to Berserk‘s dark manga atmosphere, various elements of the Neon Genesis Evangelion animated series, and the Sister Princess animated series, which inspired his deconstructive and satirical approaches to eroge, harem, or stereotypes such as the perfect little sister cliché.

All the elements discussed so far are present in all of Yoko Taro’s major works, with greater or lesser expression, depending on the work. But there is at least one more feature that cannot be ignored: a soundtrack that is both classic and deconstructionist, and occasionally mixes with the atmosphere of the gameplay, feeding feelings such as sadness and melancholy. However, that Taro has worked with different composers also reflects different approaches to his musical signature in Drakengard‘s and NieR‘s music.

In Drakengard, for example, Nobuyoshi Sano used chaotic orchestration from extracts from classical music (such as by Dvorak, Debussy, Mozart, and Wagner), adding cacophony and uses of noise as an expressionist approach to the characters' sense of madness. On the other hand, in the NieR series, Keiichi Okabe also took classic inspirations, common to JRPGs since Koichi Sugiyama (Dragon Quest series), but gave great preference to songs (some of which with an invented language or with a mixture of many languages, such as Portuguese, French, German etc.), and not just as "background music", as Tucerv noted,

"...the soundtrack was not imagined, as was usually the case, to illustrate a scene, a movement or a place. Okabe did not seek to bring out the essence of these elements, nor to make his music a simple addition to the game's content. Instead, Taro Yoko set him a theme — sadness, moroseness — which he then diversified into different shades to compose the melodies. Ranging "from a quiescent sadness to intense sadness", Okabe explained, his music was designed to create the atmosphere, to permeate the game and its world, rather than to simply accompany it."

Several game design choices previously mentioned also relate to another characteristic of Yoko Taro’s direction: subverting some JRPG design conventions, particularly those dating back to Dynasty Warrior and Dragon Quest. Finally, one shouldn’t forget a striking choice of Yoko Taro’s narrative design: dialogue choices and branching narrative. Dialogue choices in Yoko Taro games are not usually frequent, but some of them, at decisive moments in the plot, can carry a lot of weight. In addition, it is recurrent in his works that there are multiple endings and different routes, which can be overlapped or direct continuations.

Conclusion

Deciphering an auteur's "signature" is far from an exact science, but it is possible to identify, however imprecisely, the elements of both content and form of an auteur's works that make them recognizable in the video game industry, and here we list some of the main features of Yoko Taro's RPGs:

- Plot that thematizes altruism, existentialism and morality;

- Denaturalization of creatures as mere "targets";

- Meta-entertainment;

- Profusion of genres;

- Otaku references (usually seinens, like Berserk, Evangelion and Sister Princess);

- Soundtrack with classical and deconstructionist inspirations with atmospheric function;

- Subverting some JRPG design conventions;

- Dialogue choices at specific moments and branching narrative (multiple endings and different routes).

In parallel with these characteristics that are more or less constant in his works, the different Yoko Taro games also have unique things. NieR's aesthetics and narrative, for example, are clearly influenced by Fumito Ueda's games, such as ICO (2001) and Shadow of the Colossus (2005), an influence that is no longer so striking in Drakengard. And in Voice of Cards series there's a strong tabletop RPG influence unparalleled with Drakengard/NieR. There are concepts and features that are unique to each of these games, as well as different approaches to the aforementioned aspects, that make each of Yoko Taro's games a memorable experience, and not simply a reiteration of his signature.

Comments

Sign in or become a SUPERJUMP member to join the conversation.