Remembering Star Wars Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II

An underappreciated gem

In mid-1997, after two years living in Kansas, USA due to my father’s work, my family returned to Australia. It was during this time that I first played Sid Meier's Civilization II and several other gems that had been released in the two years that we’d been out of the country. I began to purchase the monthly editions of PC PowerPlay magazine, and steadily work through the demo CDs that came with each issue. Game demos were a core part of my gaming in the late 90s, giving me broad exposure to a wide variety of games in a very short period. At some point, I came into possession of a Harvey Norman promotional CD. The CD had several game demos on it, and one of those demos was Star Wars Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II by LucasArts.

I was, like so many other computer game nerds, a massive Star Wars fan, and in the 1990s, games based on the Star Wars franchise had a fairly good reputation. The X-Wing series (in particular the second game, TIE Fighter) are still considered benchmark titles in the spacesim genre, and Star Wars: Dark Forces was a extemely polished take on the “Doom clone” genre, as shooters were known.

In 1996, id Software once again revolutionised the first-person shooter genre with the fully 3D Quake, and other game developers were quick to follow suit, including LucasArts. Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II was released on 9 October 1997.

Jedi Knight continued the story of Kyle Katarn, a former Imperial officer and mercenary who stole the plans to the original Death Star and delivered them to the Rebel Alliance, before uncovering an Imperial plot to engineer an army of droid soldiers called Dark Troopers. In Dark Forces II, Kyle Katarn discovers the identity of his father’s killer, the Dark Jedi Jerec. His quest for justice reveals his own Jedi heritage, and the game soon becomes a classic Star Wars tale of the clash between light and dark.

Many FPS games in the 90s attempted to emulate id Software’s games, and usually incorporated the same level of violence, a similar variation of weapons and a familiar sci-fi or action setting. Star Wars games, because of their source material, were forced to have a point of difference. Violence couldn’t be as prominent, weapons needed to fit the Star Wars lore and the setting was iconic in and of itself. That unique Star Wars flavour was what helped Jedi Knight stand out from other shooters of the era.

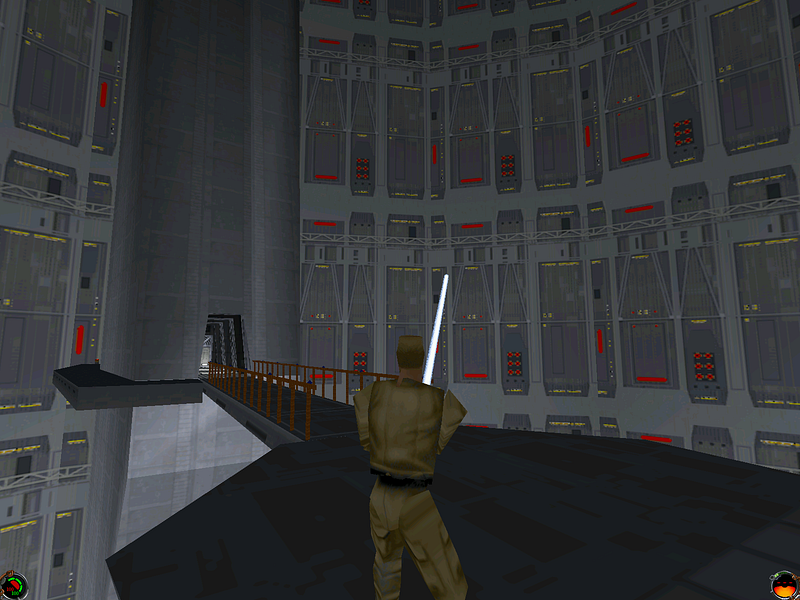

The most highly publicised feature was, of course, the ability to become a Jedi and wield a lightsaber. Jedi Knight was the first real attempt at a lightsaber in gaming, outside of simple depictions in games like the Star Wars platformers on the Nintendo and Super Nintendo. Melee weapons in other first person shooters, like the axe in Quake and crowbar in Half-Life, were usually treated as last-resort weapons for when you ran out of ammo. In Jedi Knight, the lightsaber was the ultimate weapon, difficult to use but immensely powerful in the hands of a skilled player.

Another defining feature of Jedi Knight was the Force. Force powers added an additional element to traditional FPS gameplay. In single-player, the Force allowed players to have an alternative for solving problems — disarm your enemies with Force Pull, blast them to pieces with Force Destruction, or sneak past them undetected with Force Persuasion.

In multiplayer, the Force added an entirely new dimension to the gameplay. Usually, in multiplayer FPS games, you enter the match with a weak weapon and need to go searching for more powerful weapons. This initially puts you at a distinct disadvantage against other players. In a Jedi Knight match with Force powers enabled (the amount of Force powers available in a game could be configured by the host), you were no longer helpless. Skilled players didn’t even need to search for weapons — with their lightsaber and the Force, they could easily defeat any foe. The Star Wars licence helped Jedi Knight stand out as a unique game, not just for its setting, but for the emergent mechanics that came from the setting.

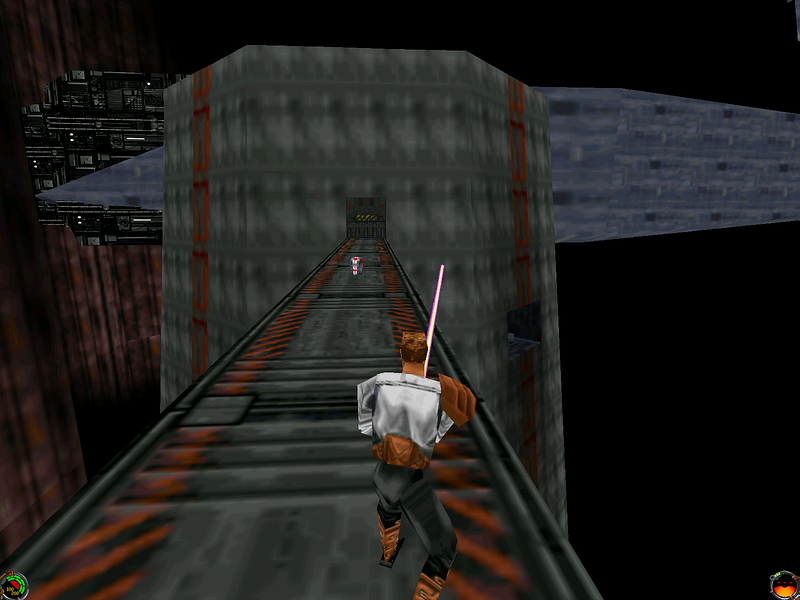

The demo of Jedi Knight on that Harvey Norman CD had two levels in it — a sample of the single-player campaign, and one of the multiplayer levels. The single-player level was taken from about half-way through the main campaign, as the game’s protagonist Kyle Katarn is attempting to board a freighter that is about to depart a refuelling station controlled by the Imperial Remnant (the game is set approximately one year after Return of the Jedi).

Barely exaggerating, I must have played this level almost a hundred times. I explored every nook and cranny, attempting to find every secret and trying all sorts of different strategies in defeating the level. This was how I discovered one of the easter eggs in the level — When leaping across to the departing freighter at the end of the level, if the player turns around they will see the face of Max the rabbit from the LucasArts adventure game Sam & Max Hit the Road grinning back at them.

Jedi Knight was also my first experience of multiplayer. The included level was called “Bespin Mining Station”, and was designed for about four to eight players. A TCP/IP connection could allow multiple players, but back in 1997 I didn’t fully understand network protocols, so I played Jedi Knight with a friend down the street in the simplest way available — a direct modem-to-modem connection. With two modems directly connecting to each other, this set the multiplayer player limit at two.

Setting up a modem multiplayer game was an adventure by itself. You’d have to time it well, so that the player at the other end of the line had hosted the game and was listening for the connection. If a parent at either end picked up the phone to call someone, this would disrupt the connection and you’d have to start again. And it happened all the time. No matter how many times we’d tell them not to pickup the phone if it rings because it was just a game connection, they’d still forget and do it anyway. And that was just trying to establish a connection — even after successfully getting a game up and running, there was still the danger that someone would forget the phoneline was in use, and would pick up the handset only to hear a shrill data stream in their ear, which would be promptly cut off once they put the handset down, requiring us to go through the chore of setting up a new game. It’s for this reason that so many households in the dial-up internet era had two phonelines — one for the landline phone, and one for the internet.

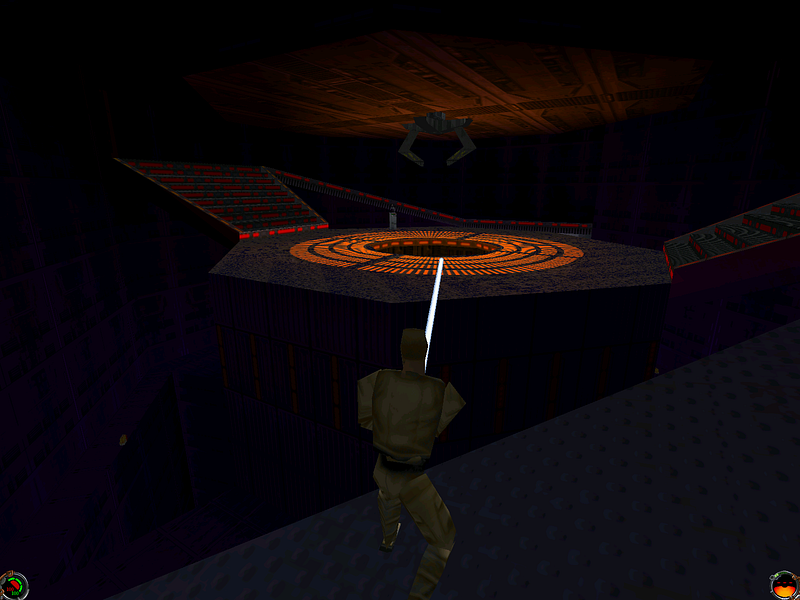

With only two players, Bespin Mining Station evoked an unforgettable feel of tension. As it had been designed for more players, having only two players meant that your encounters were much less frequent. The sound design in this Jedi Knight level heightened this tension immensely. The entire level had an audible hum, a sort of generic “industrial” sound. Elevators made a loud, distinctive whine, while powerups and switches had their own unique sound effects that were audible within close vicinity. Thanks to all this aural feedback, you could often hear the other player long before you could see them. Bespin Mining Station had no shortage of hiding and ambush spots too, such as the small ledge in each elevator shaft. Waiting on this ledge, you could get an easy frag by blasting your opponent with a well-timed shot as they travelled past you on the elevator.

From a design perspective, Bespin Mining Station had it all. The upper hallways were wide and good for fights with longer ranged weapons, while the middle level was claustrophobic and gave players with the lightsaber a distinct advantage. On the bottom level of the map was a narrow catwalk between the two elevators at either end of the level. This catwalk was the scene of many tense lightsaber duels, and one wrong step would have the player fall to their death. Of course, that is assuming the other player honourably accepted your duel — they might as easily blast you off the catwalk with a well-placed concussion rifle blast.

The Jedi Knight demo consumed a huge amount of my time, and I just knew that I had to have this game. So, I badgered my parents endlessly, asking if they would get me the game for Christmas. And when the Christmas of 1997 finally came, there it was. Star Wars Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II. I can distinctly remember sitting impatiently through Christmas lunch, itching to get upstairs and install the game, and when I was mercifully dismissed from the table, that’s exactly what I did.

The pace of the games industry in the late 90s is nothing compared to today. The holiday period always saw a few major releases, but nothing on the scale of the modern industry. Games were expected to give you several months if not years' worth of value. Jedi Knight was one of those games. The single-player campaign had about 20 levels, with the plot branching in a slightly different direction about half-way through, depending on whether the player decides to follow the Light or Dark side of the Force.

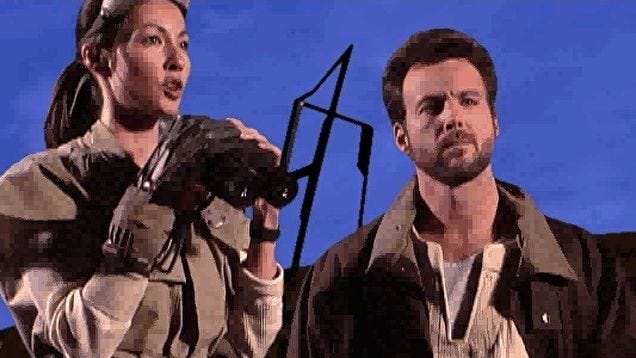

Between levels, the plot is driven by full-motion video (FMV) cutscenes, with live actors in front of pre-rendered backdrops. The acting was bad — entertainingly so. But to be fair, the videogame FMV acting bar has never been particularly high. Still, this was the first Star Wars footage that many had seen since the original trilogy (Star Wars: Rebel Assault also included FMV), and the cutscenes had the first lightsaber footage since Return of the Jedi in 1983.

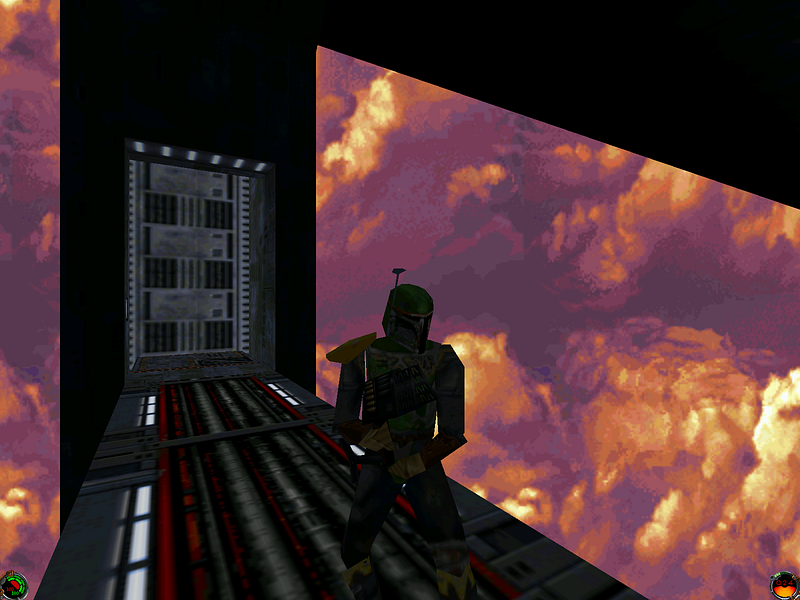

Jedi Knight was released at a time of major technical upheaval in the game development industry. In the space of a couple short years, games had transitioned from predominantly using 2D rendering to real-time 3D rendering using dedicated hardware like the 3dfx Voodoo. The result of this was that graphic design in games was diverse in execution, as game designers and artists explored different ways to utilise this new technology. 3D hardware was far from commonplace, so game developers also had to design their games with consideration for performance on non-hardware accelerated computers.

Today, Jedi Knight looks a little rough around the edges. But in 1997, the fact that LucasArts was able to put together a game engine that could look fantastic on 3D hardware while still looking good and maintaining a steady framerate in software rendering was a major feat. LucasArts’ use of polygons gives it an iconic, unmistakeable look that might be a bit jarring to today’s viewers, but for me it’s a charming aesthetic that immediately triggers waves of nostalgia.

One of the highlights of Jedi Knight was its level design. The game’s 20 levels are immense — orders of magnitude larger than levels in many modern shooters. The settings were diverse as well — the opening levels take place in the industrial rat-warren mega-city of Nar Shaddaa, while other locations include a vast farm, huge Imperial facilities, isolated desert canyons and my personal favourite, the city of Baron’s Hed.

It wasn’t just the size of the levels that stood out — they were filled with assets and NPCs that made them feel alive (at least by 1997’s standards). The NPCs acted as a minor gameplay mechanic too; strike down innocent civilians and droids and Kyle drifts towards the dark side. The “canon” path of the game (carried on through Jedi Knight’s sequels Mysteries of the Sith, Jedi Outcast and Jedi Academy) is that Kyle follows the light side of the force — however, there is also to option to fall to the dark side, resulting in Kyle becoming the new Emperor; “Emperor Kyle” is hilarious, by the way.

Jedi Knight is an excellent single-player game, but it also shines in multiplayer. The most common way I played Jedi Knight multiplayer in the late 90s was on Microsoft’s former multiplayer service, the Internet Gaming Zone. The Zone still technically lives on as MSN Games, but these days it’s just a website for playing games like Hearts and Mahjong online. In its heyday, the Zone was a hub for multiplayer Star Wars games, as well as MechWarrior 3 and the massively underrated games Urban Assault and Tanarus.

Like the level design in single-player, Jedi Knight’s multiplayer level design is excellent. Bespin Mining Station was of course one highlight, but common multiplayer favourites at the height of Jedi Knight’s popularity were the arena-styled “Canyon Oasis” and two levels perfect for lightsaber duels — “Battleground Jedi” and “Valley of the Jedi Tower”. Jedi Tower was my favourite map for lightsaber duels, as it had all the makings of an epic Star Wars battle — narrow catwalks above a deep canyon, where one misstep could end in death.

The modding scene for Jedi Knight was vibrant as well. The Massassi Temple was my go-to site for custom maps, skins and mods, and Massassi.net remained one of the primary modding sites for all subsequent games in the Dark Forces series. Amazingly, The Massassi Temple is miraculously still operating, but the forum posts indicate that the site has come close to closing on more than one occasion. Other popular Jedi Knight modding sites still active today are JKDF2.net and JKHub.

One of the best and most popular mods for Jedi Knight was Saber Battle X, which improved the appearance of the lightsabers, as well as adding new animations and adding a double-bladed lightsaber (inspired by The Phantom Menace, which was released in 1999). Another popular multiplayer mod was Manowar 2 (or Manowar 3 for the Mysteries of the Sith expansion), which was a class-based multiplayer mod featuring the iconic Mandalorian warriors.

One of my all-time favourite custom levels for Jedi Knight was Drazen Isle. Drazen Isle was designed with role-playing in mind, and was an immensely popular level on the Zone. The popularity of the RPG-style gameplay drove a boom in RPG levels and mods, such as the Baron’s Hed RPG and Mos Espa RPG mods.

Jedi Knight was followed in 1998 by the expansion pack Mysteries of the Sith. MotS, as it was known, focused on the story of Mara Jade, a popular character from Timothy Zahn’s Heir to the Empire book trilogy, one of the first and most popular works in the Star Wars Extended Universe. The level of production in Mysteries of the Sith wasn’t quite as high — no poorly acted FMV cutscenes here. However, for the price of about $30, you got a game with about the same amount of single-player content as Jedi Knight, with greatly expanded multiplayer too.

Mysteries of the Sith was never as popular as Jedi Knight, which is unfortunate — mechanics and content-wise, it was a significant improvement, and with the addition of the new hardware-accelerated “coloured lighting”, MotS looked just as good as all the other rainbow-splattered titles of the day (it was a thing…). One of my favourite additions to MotS was the class-based gameplay (called “personalities” in MotS); in certain modes, the player could choose to play as a Jedi, Bounty Hunter, Soldier or Scout, giving them different abilities and weapons. Class-based gameplay was a relatively new idea, popularised by the Quake mod Team Fortress, and MotS was one of many games experimenting with the new idea. MotS also included several levels inspired by scenes from the original trilogy, and in 1998, there was simply nothing more Star Wars than a multiplayer duel between Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker in the Carbon Chamber, or the gantry where Vader uttered his iconic line, “I am your father”.

Jedi Knight and Mysteries of the Sith certainly had longevity, and it was easy to find servers for both games right up until the 2002 release of the next game in the series, Jedi Outcast. In 2003, Jedi Outcast was followed by another title, Jedi Academy. Both games were huge leaps forward, both technically and mechanically, and they are rightly remembered as having the most fully-realised depiction of lightsaber combat in the history of gaming, especially in multiplayer.

Though Outcast and Academy are deservedly remembered as masterpieces, neither ever quite attained the status that Jedi Knight had in my life. Jedi Knight was released right at the beginning of the late 90s 3D first-person shooter boom, after Quake but before almost everything else. It is often forgotten in favour of its more widely played sequels, and was often overshadowed by its contemporaries like Half-Life and Unreal. Yet there is something that I always found admirable about Jedi Knight. Somehow, despite the immense might of the Star Wars licence behind it, it always felt like the scrappy underdog in the FPS genre — perhaps it lacked some of the polish and refinement of other games at the time, but few games could compare to the amount of love and personality that had been poured into its development.

I wouldn’t necessarily call Jedi Knight the best game ever made, not even in my own opinion. However, there is little doubt in my mind that no other game has left a greater impression on me than this underappreciated gem, and for that, it will always be dear to my heart.