The Difference Between Cohesion and Coherence in Video Games

Understanding the dichotomy between internal and external analysis

If we understand video game media as a language and particular video games as works — such as the relationship between language and books — then we can observe games from an internal point of view (the phenomena of its language) and from an external point of view (in agreement or disagreement with the proposal of the work). This piece will offer an introduction on how to understand this difference in video games.

As introduced in my essay 'The Difference Between Complexity and Depth in Video Games' (2022), everything starts from the premise that we can observe video games with sign systems with “rules of use” (which can be violated in case of experimentalism) and “meanings” attributed to them and identified by the players who interpret them. This semiotic/linguistic premise is widely accepted, but it is not consensual. If you find yourself not agreeing with this premise, I argue there are still items in this text that can be useful to you.

Let’s begin by distinguishing the “internal” and “external” scope of interpretation when experiencing a work.

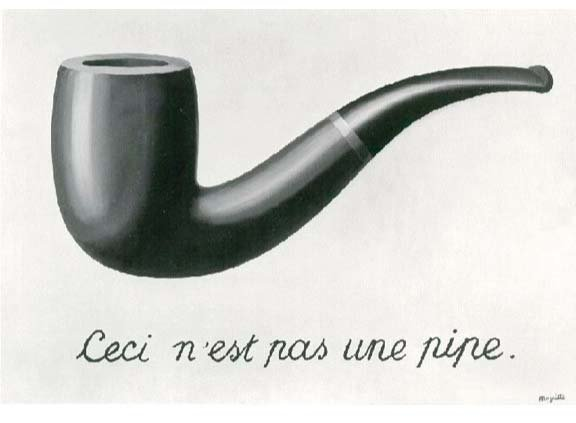

Looking at the painting above, you may have found something strange. It has a highly realistic design, as seen from the care with details, colors, lighting, proportions, and perspective. Apparently, it represents a street in a city, but there’s a disproportionately huge fly in the middle of the street.

“That makes little sense," you might think. Or “why is this giant fly there?”, you might ask yourself. If you think it makes little sense, you’re probably looking at the work 'from the inside', and you’re seeing a lack of cohesion between the design choices. If you are asking yourself why the artist painted it this way, then you are looking at it from an 'outside point of view', you are asking yourself about the coherence between what was done and what the author intended to do.

My intention with this painting is to give a good intuition about what I want to explain from here. When we observe game design choices in a video game, we can analyze them internally (observing the cohesion between these elements) and externally (observing the coherence between the game design elements and its proposal). In the next topics, I will delve deeper into these concepts and show how they can be independent and can provide novel experiences.

From a strictly linguistic (natural language) point of view, the usual definition of ‘coherence’ is logical and hermeneutical, meaning that it involves argumentation and interpretation, while ‘cohesion’ is more related to grammar. When we apply these concepts outside of natural language, we need to be careful, because it is not a perfect analogy. However, this will be our starting point:

Cohesion refers to the surface structure of texts, on how words and sentences are organised to form a cohesive whole.

Coherence refers to deeper structures (not surface structures) in texts. It involves a semantic (meaning) and pragmatic level.

Internal/Superficial Interpretation and Cohesion in Game Design

Let’s start with the surface. When we experience a game for the first time, even with little prior context about what it is about, we can perceive certain internal consistencies or inconsistencies in its design, regardless of why they are there. At this superficial level of analysis, it is unnecessary to know about the author’s intentions or the context in which it’s presented. All we need to know is how the game’s systems work and how their elements represent things.

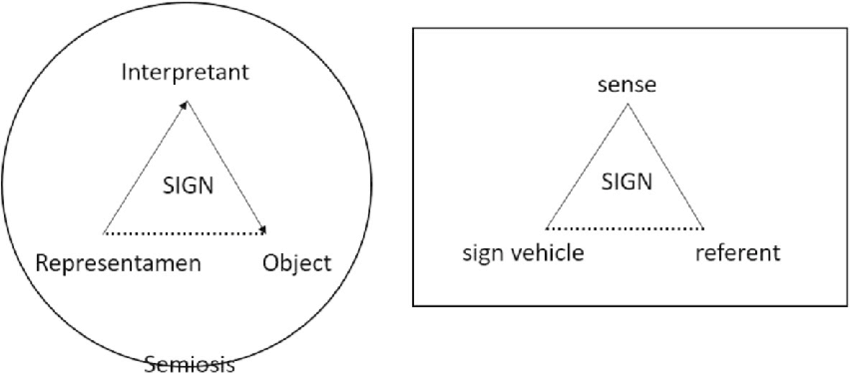

Representation here is a special function. In the Peircean sense, it is a function established between signs (things that communicate meaning). It is a function that describes a process: (1) “that which represents something”, a sign (representamen); (2) the referent, semiotic object of the sign (real or fictional); and (3) the “sign meaning” or interpretant sign, which is an interpretation of the sign in terms of other signs, for example, when we do a “translation”, or for example in the paragraph where I described part of what is in that painting by Hanno Karlhuber.

In this way, we can define cohesion only with the concept of representation (representation being a special type of function between significant game design elements, references, and meanings):

- Given a video game C, C defined as a set of significant game design elements c1, c2, ..., cn (comprising mechanics, music, sprites, models, etc.) that may have references to things and states (semiotic objects) within a fictional world: a subset C’ of C is said to be incohesion if and only if it has two or more c elements that aim to reference something in common, but suggest contradictory meanings;

- Conversely, a subset C’ of C is said to be cohesion if and only if it is not incohesive (see the definition above).

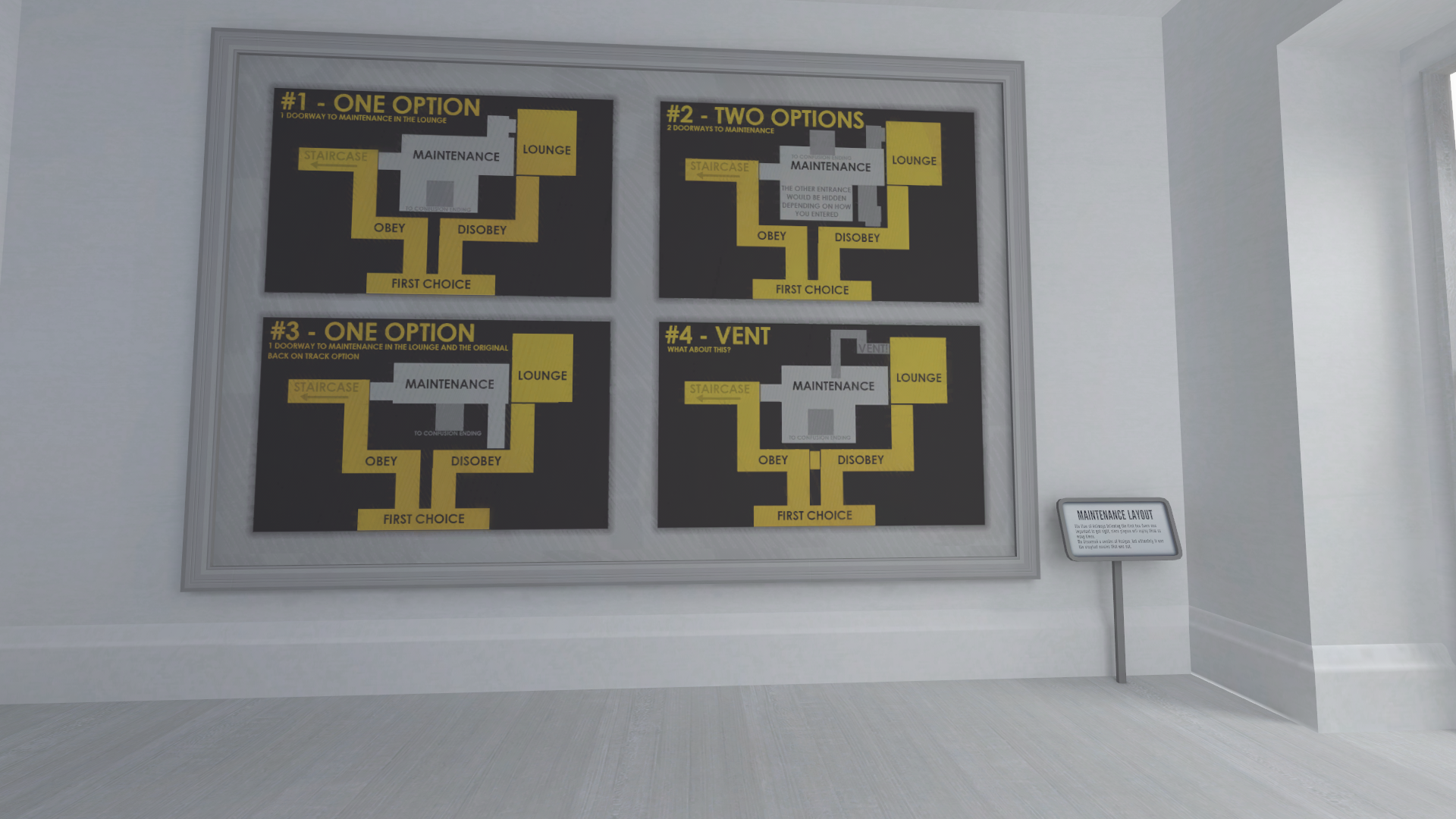

A couple of examples: Final Fantasy Pixel Remaster (2022) and Dragon Quest V, mobile version (2015), both by Square Enix. In the first case, we have an RPG with a menu that references the state of its characters, among which is the state of “death”, and we also have in-game sprites that reference these characters in the fictional world. However, when a character is dead, he appears on the menu, but it is possible to see him and walk with him during the adventure as if he were alive. Under analogous conditions, this does not occur in Dragon Quest V, where the dead character is represented as a coffin.

From left to right: Final Fantasy Pixel Remaster. Source: Critical Hits.; Dragon Quest V. Source: Author.

In the first case, we have two design elements c1 (menu) and c2 (character sprite) that comprise a subset of a video game and that reference the same object (character), but contradict each other about what they communicate about its state, therefore, a case of incohesion. In the second case, corrected this problem, in an analogous context, it is a case of cohesion.

Note that incohesion between the two design elements can occur even if they are “different in nature”. In fact, while the characters menu, for example, can present a symbol (for example, a cross) to mark that a character is dead, the coffin sprite that replaces the character is not a symbol, but an index, the fact of other characters carrying him is directly related to the fact that he died, it shows his death.

Peirce’s theory identifies three types of relationships between a sign (representamen) and its object/reference: Icon (a sign that physically resembles what it stands for), Index (a sign which implies some other object or event), and Symbol (a sign with a conventional or arbitrary relation to the signified).

External/Deep Interpretation and Coherence in Game Design

As I demonstrated in 'The Difference Between Complexity and Depth in Video Games' (2022), we can find this difference between surface and deeper structures in video games. In this topic, I will show how this ‘deeper level’ (of context and meaning) is associated with the coherence or incoherence of video games.

On the occasion of the text I mentioned above, I applied the Fregean theory of meaning. More attentive readers may notice that the theory is not equivalent to Peirce’s theory. In fact, they have some differences. However, they are not totally incompatible, both are based on the relationship between sign and reference.

Fregean theory is preferable in some cases, as for differentiating ‘sense’ from ‘meaning’ and identifying different ways of presenting meaning. Peirce’s theory, on the other hand, has advantages, such as the fact of differentiating types of signs, such as icon, symbol, and index. In this article, I used it in order to show how different signs, such as a cross (symbol) in a menu interface and a coffin (index) sprite, can lead to contradictory meanings, even though they are design elements of a different nature.

Having made this necessary comment, it is possible to adapt the concept of 'depth' as presented there. The depth of a video game is in its meanings (its semantics), therefore, and not in the functioning itself of its systems (its syntax). Cohesion, as discussed in the previous topic, also has to do with semantics, but in a shallower sense, on the surface of the semantics of a video game.

Cohesion and incohesion are recognizable to the player when experiencing and interpreting a video game on its surface, without asking why the developers did it that way, without asking what exactly the developers wanted to communicate. Coherence and incoherence are only recognizable by the player if, beyond this surface, he tries to look for contextual and argumentative reasons for game design choices. The concept of coherence presupposes a “proposal” or “intention” so that it can be ascertained whether the elements in a video game make sense of that proposal or intention.

Fortunately, I have already presented a formulation of the concept of coherence in my essay 'The Definition of Design by Subtraction' (2021), this is because this concept is fundamental to the understanding of Fumito Ueda's design philosophy. Below is an adaptation of this concept for the context of this article:

- Given a set P with one or more proposals p1, p2, ..., pn of experience about what a video game C intends to communicate, C a set of game design elements c1, c2, ..., cn (mechanics, music, sprites, models, etc.) capable of expressing it: C' subset of C is said to be incoherent if and only if the experiences or concepts resulting from its elements c are contradictory;

- Conversely, C' is coherent if and only if the experiences or concepts resulting from these elements are not contradictory.

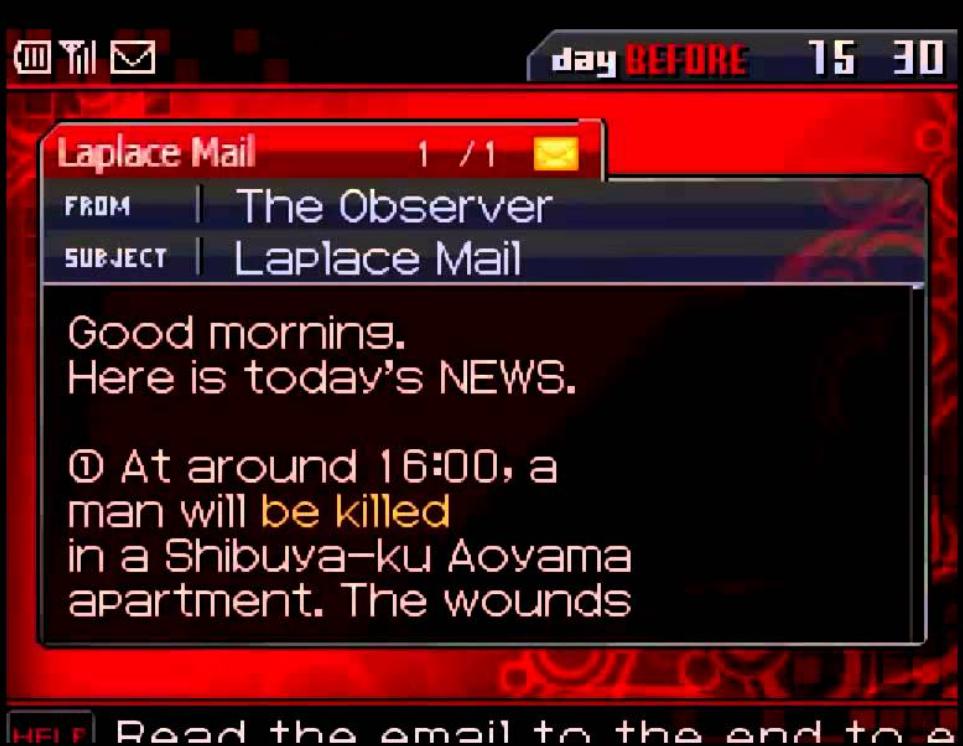

From a ‘coherentist’ point of view, we can say that a video game C is successful when it achieves its proposal P — assuming that it’s set of proposals P has no contradictions. But we can also observe this phenomenon partially, analyzing parts of a video game that are coherent with their respective proposals and others that are not. Consider the case of Shin Megami Tensei: Devil Survivor (2009) by Atlus.

Devil Survivor is a tactical RPG that, among its central proposals, is the adaptation of the philosophical hypothesis of ‘Laplace’s demon.’ The concept emerged in an article by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1814, in which he argued humans are not really ‘free’ in their choices since if there was something capable of calculating all the variables in the universe at a given instant of time t, he could predict what the universe would be like at a time t’ immediately succeeding t. He could even predict people’s actions.

From left to right: Shin Megami Tensei: Devil Survivor. Source: LeghionPlays (YouTube); Source: Tumger.

Today, various arguments highly question this hypothesis, in thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, chaos theory, and other areas. A lecture by Stephen Hawking (1999) provides an excellent introduction to this issue.

Returning to Devil Survivor, the game has a system called Laplace Mail that sends characters a prediction about future events. With this information, the protagonists can 'change destiny'.

In this TRPG, the protagonists can know when people will die, if it will be one, two or three days from now, for example. However, if the adaptation of the philosophical concept were rigorous, even if they had information about the future, Laplace’s demon should be able to know what his actions would be in the face of that information and then revise the calculation of when each one would die. Once the number resulted from this calculation, it would still be impossible to change the number of days left in someone’s life.

This incoherence of game design with that philosophical concept is not only representational but also impacts experience. After a while, the player is no longer afraid that a character will die soon, as he knows he can prevent that death from happening. He is not facing fate, but a calculator that is always wrong, depending on how the player plays. In the second half of Devil Survivor, the experience improves, and in the end, there are some justifications that mitigate this incoherence.

So as not to go too far into this topic, if you want some counterexamples (cases of coherence of game design), I invite you to take a look at 'Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne as a Political Philosophy Experiment' (2022).

Final Considerations

As we have seen throughout this essay, it is possible to make more internal/superficial and more external/deep interpretations of the game design choices of a video game. In the first case, we are looking for cohesion between the elements, in the second, the coherence between them and the video game's proposals, and what it wants to communicate to the player.

At first glance, this distinction may seem unimportant, but having clarity about it can help us better interpret the choices in a work. Let us take up the case of Hanno Karlhuber's painting at the beginning of this text. Although the viewer may conclude that the painter was not cohesive with the proportions of his painting, if he thinks about the coherence of the work with the proposal, he will discover that it is a very coherent work, as a work of the magical realism art movement. That is why it is important to know the proposal of work before judging its coherence.

Knowing this distinction well is also useful for developers. As Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman show in Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals (2003), video games comprise an incredibly complex system of signs, so a slight problem of interpretation can have huge consequences for the player’s experience.

Thus, the lack of cohesion between the elements of a video game can lead to a lot of confusion. In Final Fantasy, if the player forgets that his character is dead, by seeing him while walking on the map, enemies can surprise him when he enters a battle, and even lose it for not having that unit available in combat. So if the lack of cohesion is intentional (as in Hanno Karlhuber’s painting), you have to be careful.

In addition, it is recommended to have a very clear idea of what you want to communicate in your work and to make choices that are coherent with it. In this way, you will prevent the player from having contradictory experiences, and that one will cancel out the impact of the other.