The Mind of a Child

"Imagination is more important than knowledge"

“When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I gave up childish ways.”

1 Corinthians 13:11

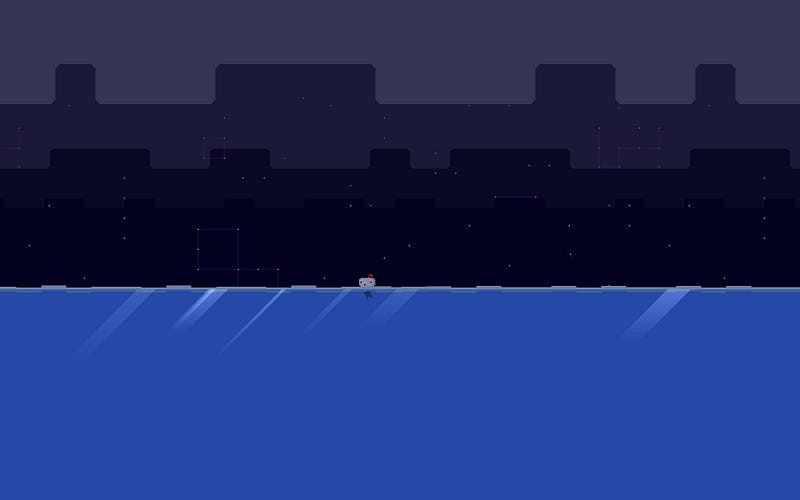

This is a screenshot of my then-three-year old daughter playing Fez (Polytron Corporation, 2012). She was walking around on one of the game’s islands, and decided she wanted to “swim to another city”. So, she jumped in the water and just kept swimming. As an older gamer, I am aware of the limitations of games, and the invisible walls that developers put up to give the illusion of freedom. But a three-year-old has no such concept. All she saw was a limitless digital world to explore and interpret with her childish imagination of infinite possibility.

This experience made had me analysing my own evolving perspective towards the games I play. These days, I am often a task-focused gamer. I need a narrative, or a series of goals or quests, to hold my interest in a game. I am usually aware of the hidden boundaries laid by developers, so I rarely seek to go beyond them. I know, for example, the approximate angle of a hill that makes it “unclimbable”, so I won’t bother trying. I know what a skybox is, and I can tell where assets have been placed to give the illusion of a larger game world than actually exists. So when I see mountains off in the distance, I acknowledge they look nice, but I know that I can’t reach them. So, I don’t try. With my years of experience in playing games, I can usually spot procedurally generated content a mile off, so I’m not filled with a sense of wonder when I encounter the thousandth variation on the world environment; I know that it is likely just going to be another location with a slightly different combination of assets.

Becoming an older gamer invariably coincides with becoming a more discerning and cynical gamer. That is good, in some ways — I am more resilient than ever against the marketing ploys of triple-A studios, and I have the maturity and sense to resist the subtle psychological tricks that developers use to bait you into microtransactions. However, something is lost in the experience of games as you journey down the path towards becoming a grumpy old gamer.

When I was younger, I too had the spark of perpetual optimism about game worlds like my daughter did in the above example. I was constantly seeking out the limits of what I could do in a game engine, and when I found those walls, I would carefully search along them for cracks that might reveal some new doorway into an unexplored corner of the game world. It was this approach that showed me all the illusions that game designers use to make their worlds seem so much larger and expansive. In Big Red Software’s 1996 game, Big Red Racing, each track was situated in a seemingly endless flat plain. One day, after becoming bored with racing, I decided to set out across that plain, to see where it would take me, and I discovered that I would just reappear on the other side of the map. The maps where each track was located were essentially globes with no discernible features other than a racing track.

In the case of my daughter playing Fez, she kept swimming for several minutes, and as I already suspected, she discovered nothing. Eventually tiring of her journey, she turned around and swam back. When she finally returned to the island she started from, she exclaimed “look Daddy, I found the new city!’ Where her inquisitive child’s mind did not discover what she was searching for, her imagination took up the helm and filled the void.

This is another element of why children and adults experience and interpret games so differently. As Peter Pan (JM Barrie, 1911) and other literary works have explored, our imagination slowly atrophies as we get older. This is backed up by research as well; research from the Psychological Science journal found that ageing makes the imagination wither — surely, one of life's most tragic realities.

As I have become an older gamer, I have learned about the boundaries that exist in the game worlds I play in, and I started to learn about those boundaries many years ago. But if I had a much stronger imagination guiding me, those boundaries might not seem so significant. My mind could easily create the experience I sought within the limitations presented to me.

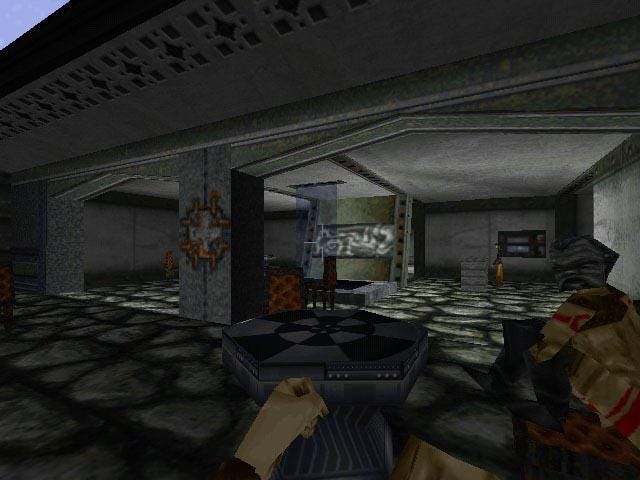

For Christmas in 1997, my parents gave me a copy of Star Wars Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II. I had been playing the demo of Jedi Knight for several months, which included a single level from about halfway through the main campaign, as well as a single multiplayer level, Bespin Mining Station. Jedi Knight released in September 1997, so I’d been playing these two levels non-stop for several months. When I wasn’t able to use the phone line to play modem-to-modem multiplayer with my friend down the street (“MUM! GET OFF THE PHONE!”), I was making multiplayer characters and exploring the levels on my own. As for the single player level, I had played through it dozens of times, and had explored every nook and cranny, using cheat codes to help me reach areas that I couldn’t otherwise get to. This was how I managed to discover the little Sam & Max Hit the Road Easter egg (if you turn 180 degrees right at the end of the level, you are greeted by the smiling bunny, Max).

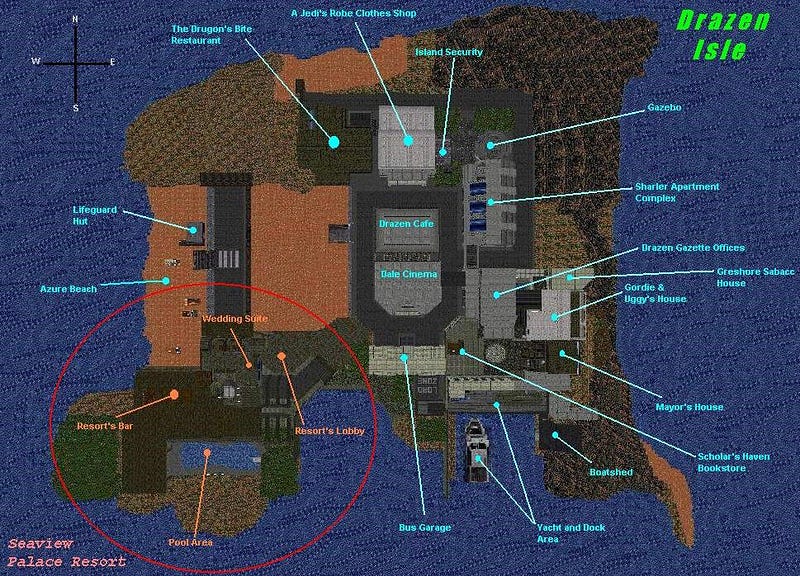

Those two levels, so limited in their scope and freedom, had entertained me for hours on end, my imagination filling the spaces that the game couldn’t. When I finally got to play the full game, I was entranced. Besides the huge levels of the single player game (Jedi Knight really is underappreciated for its level design), I got involved in multiplayer quite heavily on The Zone, Microsoft’s free online games service that was popular in the late 1990s. The modding scene for Jedi Knight was incredibly active, and one of the custom levels that eventually rose to prominence was Drazen Isle by Jeff Walters, which you can still get at the popular Jedi Knight series mod website The Massassi Temple. That this website is still running in 2023 is surely a miracle, and kudos to them for keeping this piece of history alive.

Drazen Isle takes place on an island resort, and features areas like a shopping district, hotel, a yacht and a beach. The download came in a whopping 3.04 megabytes — a pretty massive file compared to other levels on offer at the time, and requiring a little bit of patience on my old 56k dial-up connection. In the zip file was, of course, the “town.gob” level file, but the download also included a map and the "Drazen Isle Tourist Guide", which functioned as a combined Readme and game guide for this enormous multiplayer level.

Walters had added many scripted events to the level to encourage different modes of play, such as the “Treasure Hunt”, a PA system, and a tour bus. Arising out of these scripted events and the design of the level, was an emergent gameplay mode — Drazen Isle RPG. Players would advertise their games on The Zone as RPG games, where the expectation was that you would pick a “role”, such as police, criminal, shopkeeper, tourist, etc. and would be expected to play that role in the game. Chat messages are broadcasted to the entire level, and this was in the days before voice comms were common, so the expectation was that you would roleplay and only respond to messages from a character that was in speaking distance.

There was no mechanic to stop a player entering one of the level’s shops and just picking up all the powerups. And there was no in-game currency. Regardless, players were expected to go through the process of role-playing their weapon purchases. A player would enter a shop, use the “activate” key on the shopkeeper to simulate the handover of cash, and then they would be allowed to collect the item they had “purchased”. Criminals could enter a shop with a weapon and hold it up, and then police would hunt them down. Meanwhile, other players would just walk around the level, playing out the mostly mundane roles that they could imagine.

The mechanics of Jedi Knight were not exactly conducive to this mode of play, and what mechanics did exist were extremely limited from an RPG point of view. But that didn’t stop “Drazen Isle RPG” games from swamping the Jedi Knight game lobbies on The Zone. This was an incredibly popular way to play, and other modders soon released their own levels with more extensive modifications to the game’s code to better enable RPG mechanics (such as the Baron’s Hed RPG mod). But despite these mods doing an arguably better job than Walter’s Drazen Isle, they never achieved the same level of success.

I can’t really imagine myself getting as involved as I was with something like Drazen Isle again. Firstly, the games industry has changed immensely in the two decades since Jedi Knight’s peak, and expectations of what constitutes an engaging gameplay loop have shifted significantly. But that is what it is. The real factor that limits me from returning to those days is imagination. I like to think I have a very active imagination, I’m generally a creative person and I like to draw and write. But sadly, I still feel my imagination slipping from my grasp, slowly but surely, as the years march on.

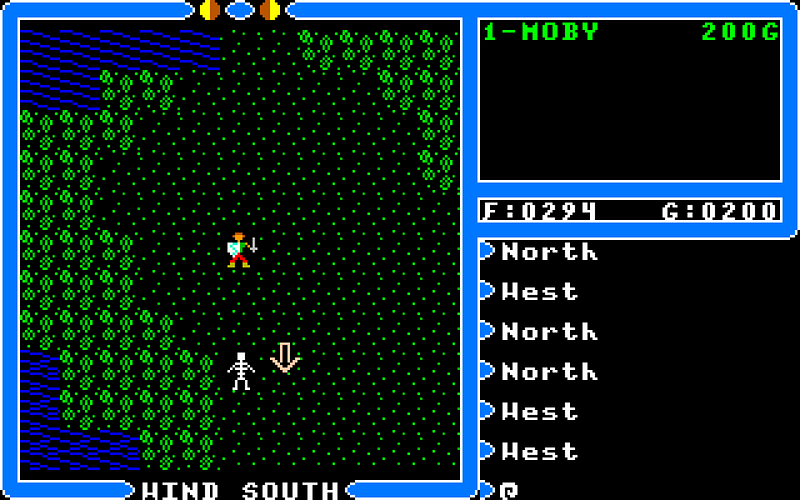

I think imagination is part of the reason why classic/retro games often fade into obscurity, and many modern gamers struggle to appreciate them as they once were appreciated. At the time of its release in 1985, Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar (Origin Systems) was an impressive game. A huge world to explore, a gripping quest to become the Avatar. For gamers at the time, this was the standard for representing a world. Technology has advanced so far since then, and gamers expect more from digital representations of worlds. So, for someone to appreciate what made Ultima IV brilliant requires significantly more imagination today than it did back then, because we have greater expectations of what is possible. What was once a noble figure of virtue heading off on a quest through a dark and mysterious forest is now a simple stick figure, holding a pixelated cross representing a sword, walking through a mass of green blobs that somewhat resemble trees. For someone who is used to the vibrancy of Velen or Skellige in The Witcher III: Wild Hunt, this is quite the leap in imaginative adaptability. Not to mention that the actual mechanics involved in playing the game are archaic, and an obstacle to learning how to play the game itself.

I don’t mean to say that graphics are more important than gameplay. I definitely don’t mean to say that, because it is not true, and the retro game revival over the past decade is evidence that the games industry has matured beyond that. But not all games stand the test of time, and the successful ones are usually ones that have some sort of “timeless” factor about them (farm management in Stardew Valley, for example), or some other element of immersiveness that overrides any graphical limitations (total freedom of exploration and Lego-like creativity in Minecraft). Meanwhile, a game like Ultima Underworld (Blue Sky Productions/Looking Glass Studios, 1992), which is regarded as one of the most revolutionary achievements in game design ever — hasn’t really aged as well as other games from that era.

The great thing about imagination is that it can transform the intended experience of a game into something entirely different. In the late 1990s, I spent a lot of time playing Need for Speed II: Special Edition (Electronic Arts, 1997). The races got old eventually, especially if you weren’t in a competitive mood. However, the great thing about the physics engine in these old Need for Speed games was the obscene crashes you could create. Hitting a car on the right angle could send you soaring through the sky, rolling down the road long after an object like a car realistically should. Eventually, this became the standard way my friends and I would play the game. Split-screen multiplayer, entirely ignoring the objective of racing. Instead, we would drive around trying to cause epic pile ups; as a side note, I think this is why I so thoroughly enjoyed Crash Mode in the Burnout series.

At some point, and I don’t recall how, but our crass teenage minds became obsessed with the notion of “mating” the large semi-trailer cabs (Mack trucks, as my friend called them). We would drive around the level, find two Mack trucks to flip over with some skillful crashing, and then push them together. Shortly afterward, a third Mack truck would drive past, and so we came to the conclusion that we were breeding trucks.

This sounds ridiculous, and it was, but regardless, we spent hours upon hours doing this. I don’t know if this actually works — I haven’t tried to replicate it for empirical study. I think it is far more likely a consequence of the technical limitations of the game engine, such as only rendering three trucks at one time, combined with a healthy dose of our own childish confirmation bias. But whether it was simply our misinterpretation, or whether we had somehow discovered some sort of obscure Easter egg in the game (and to be honest, I wouldn’t put it past a game developer), the main thing is that we had an enormous amount of fun with imagination-driven emergent play.

Emergent gameplay is one reason why I believe games are one of the most important developmental tools in a parent’s arsenal. Game worlds provide a safe and engaging way for a child to explore the concepts of cause and effect and consequence, in addition to all the other valuable lessons they can learn, such as resource and time management. When children play games, they are constantly testing the world to see what happens when they do something. They are learning critical problem solving and analytical skills. I’m reasonably certain that a two-truck pile up on a real-life highway isn’t going to result in more baby trucks driving past, but what I was learning was foundational ideas about how to analyse a situation (an in-game car crash), develop a hypothesis (two crashed trucks equals a third truck) and come to a conclusion (you can breed Mack trucks in Need for Speed). It's not the sort of academic brilliance that will lead to a Nobel Prize, but it is fun.

I often lament the fact that each year, my imagination is becoming more and more obscured behind the cold, rational facts and experiences of adulthood. Sometimes, it will ruin a game for me. I thoroughly enjoyed playing Conan: Exiles (Funcom, 2017) initially. A large, immersive world. Great graphics. Enjoyable gameplay. But several hours into playing the game, the imaginative part of my brain lapsed in concentration, and the cold, rational part stepped in — “What are you doing?” it said. “This game has no objective. What is the point?”

And just like that, I stopped having fun, and I stopped playing it.

How do we combat this, as adults? Firstly, through shared experiences. The great thing about the games of today is that it is easier than ever to play online with others. Playing a game that constantly demands you use your imagination can be a chore. If you share this experience with others, you are lightening the load. Where your imagination falters, theirs might pick up the slack.

In the absence of others to play games with, some studies have also suggested that imagination improves with practice. Imagination is like a muscle — if you don’t use it, it degrades; conversely if you constantly engage it, it becomes more adaptable. Albert Einstein himself stated that “imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.”. Imagination isn’t just some trivial, fanciful thing children engage with — it is a valuable skill to develop for your personal and professional life.

They don’t realise it now, and won’t for many years, but for my children, their experience of games is vastly different to my own as an adult. I engage with them now as a hobby, a source of enjoyment where I get to experience excellent stories or explore fantastical worlds presented to me. For them, they aren’t just exploring the worlds presented to them. They are creating their own unique worlds within the worlds created for them, forging important neural links and exercising creativity that will serve them for the rest of their lives. And for that, I envy them.