The Unbearable Humanity of Inanimate Objects

Tetris Effect: Connected, Unpacking, and finding personhood without people

I don’t think it’s possible to prepare someone for the concept that a falling Tetrimino could make them cry.

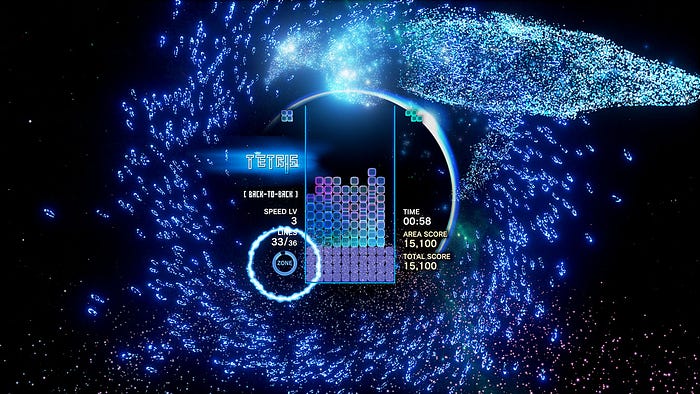

Early on in Tetris Effect: Connected, the game presents itself via conventional expectations — familiar shapes fall, you spin or hold those shapes, you find where each one fits, and you clear lines. With every movement, spin, and hold, the pieces hum with musical notes that are synthesized to match the chord progression and beat of the tune playing in the background. The music itself is lovely, soothing, and hopeful. It plays out dramatically against a neon abyss of heightened color and pulsating graphical effect — wherever this is taking place, it is nowhere on Earth.

The song — played first and last, bookending the experience — gains new meaning with steady progression.

“I’m yours forever.

There is no end in sight for us,

Nothing could measure

The kind of strength inside our hearts.

It’s all connected.

We’re all together in this love,

Don’t you forget it.

We’re all connected in this.”

Tetris is one of the most immediately recognizable forces in all of franchise gaming. It’s older than many of us — it’s older than me. Tetris is simple, and complicated, and somehow it continues to evolve and change and grow against a widely-known pattern, its rules obvious, its laws governed by a repetition that is both addictive and cathartic. Tetris Effect: Connected, surprisingly, adds an element to the formula I never expected to find: humanity.

A Philosophy of Things

Without deep consideration, all of us assign a human value to inhuman things. The glass we use to drink water from each day, the favorite blanket, the worn stuffed animal, the car keys with the ornament that has been on the ring for years, a rock found in a river that has never moved from its place on your desk. Some of these things were made by human hands, and some of them are given value purely because of the human emotions they elicit in their viewer. Inanimate objects carry unbelieve force because they are imbued with the passions and love of their human counterparts — they are special because they are decidedly so.

As the Tetriminos fall, as the music swells and plays and warps and changes based on my pieces, as I clear lines, as the backgrounds change from party lights to outer space to the swirling imagery of animal and culture, decisions are rapidly made. These decisions not only impact the outcome of the level but the attachment to a particular moment, to a piece, to where a particular thing belongs. As the next piece folds into the black and my eyes quickly ascertain the geography and dimensions of my rapidly changing Tetris landscape, my brain immediately makes a value decision on where it belongs, and where it should stay.

In Unpacking, an indie puzzle game published by Witch Beam, we categorize the objects that comprise a human life across a number of years. It starts small, in the cradle of any lifetime — a child’s bedroom. As we open brown moving boxes and unpack items carefully stowed with crumpled brown paper, objects are revealed: a soccer ball, a stuffed animal, a backpack, a diary, a camera. Wordlessly we place these items where they belong — no one has told us where a particular item is meant to go, where it lives, where it stays. We know because we assign placement, value, and worth to these items at a glance, tucking them into their implied locations, putting them where they fit on a desk, in a nook, on a shelf.

Unpacking is a titanic example of environmental storytelling and a sobering look through the stages of life that is completely devoid of physical humans or even language. As the years pass and the locations change — waxing and waning with college, partners, dorm rooms, apartments, and finally a home — the implications of what we are seeing hit the soul as effectively as any narrative I’ve ever personally experienced in an exposition-filled RPG. With every move, the objects that are kept, lost, or replaced brim with emotional language. We know where these things belong, and sometimes that belonging is so devastating that it takes a moment to continue, despite the brightness and color that fills every space.

Unpacking A Life

Taking place between 1997 and 2018, Unpacking may be the single most sobering look at the humanity of physical space I’ve ever experienced, all of it lasting only a few hours. The game is uncomplicated — while Tetris Effect: Connected made me work, Unpacking felt like the due opposite. Each snapshot is directly inspired by the stages of a staged existence, and the changes that occur every time a move occurs. What is worth keeping? What items receive the glorious treatment of a shelf, and what items from our past become unceremoniously shoved in a closet or beneath a bed?

It is not only the person who changes but the objects themselves — video game consoles are replaced by newer iterations, stuffed animals rip and fade, clothing is replaced when band shirts lose their relevance in favor of a business blazer, DVDs become Blu-rays. If life is measured in its details, there is more to learn about a person in what they keep than in what they say.

Particular details build a narrative wordlessly, revealing the heartbreaking decisions that mold a particular life. Personal objects that were once placed on mantel and desk and tableside are shoved under the bed when moving in with a partner. Favorite kitchen tools and accessories are proudly displayed where there is room, and forgotten when there isn’t. The stylistic choices that carefully curated the entirety of a living space are abandoned when the evidence of a new child comes into existence.

Successes are there, too — in the passing years, Unpacking tells a story of optimism, where awards are placed on walls and the fruits of labor divided up against seasons and homes now adorn brand new space. The iconography that adorns individual items tell of cultural and religious significance, down to the very bones of the home. It is significant, what a person chooses to adorn their living space with.

After some effort, I place my final Tetrimino and clear the final line. The music swells, slows, fades. My reward for pushing myself through the challenge presented in Tetris Effect: Connected is not a narrative beat, not a final cutscene, nothing tangible at all. I am satisfied because the pieces I’ve placed were done so by my hand, the choices oftentimes made rapidly and with barely any conscious thought, all of it existing to bring me into a future moment where I can sit back, relax, reflect. With every cleared line things get a little easier. With every advanced stage, things become a little more difficult. Colors change. Notes differ. Somehow, at the end of it, I am still myself, and I am not.

Connected Through Objects

The objects that make up a life all hold power. A salt container sees a dorm room, sees an apartment, sees three different kitchens. A handheld video game console always finds its place on the bedside table, on a coffee table, in easy reach. The same brand of shampoo and conditioner is used for years and years, not because it’s necessarily better or worse than any other, but because there is an anchoring comfort in the familiarity of that particular combination of bottle shape, color, and logo. A pink pig stuffed animal carries the same power as ensuring that the held Tetrimino is the long blue one made up of four squares — both of them containing the power of belonging, always knowing where they should go, empowering their owner with a sense of familiarity, strength, and security.

The objects that truly connect us, the inanimate pieces that push us forward, that hold us back, that construct the very spaces that give credence and dimension and complexity to a life, they have power because we have imbued them with fragments of ourselves. There is significance in the souvenirs that represent our temporary adventures, an emotional trigger in finding new places for old things. A coffee mug that sits on a store shelf is meaningless. That same coffee mug — twenty years and countless homes later, chipped and faded and well-used — has an incalculable value, one that we can never truly know.

I find the perfect spot for my falling Tetrimino, hastily putting it away, waiting for the next to fall. I pull out my favorite stuffed animal, from 1997, and place it in my child’s crib in 2018. These objects travel the black void of time like blocks, like pieces of a life. The items that have value always find their places, surrounding us, filling in the gaps.

“It’s all connected,

We’re all together in this love.

Don’t you forget it,

We’re all connected in this love.”

— Connected (Yours Forever), Hydelic