Unfiction and Digital Horror: The Evolution of Games You Can't Play

Is it real or is it unfiction?

Hey guys, I just wanted to start a record here. This... this application just showed up on my computer. I’ve tried deleting it; I’ve tried factory reseting my computer; I’ve tried installing one of those security scanners to check and see if my computer has a virus; I’ve even bought an entire new computer. But it’s still there. I can’t even move the icon on my desktop. I have to know what’s in here, why it keeps showing up on my computers. I finally got the courage to open it, I mean with the fresh computer I’ve got nothing to lose if it’s a virus or hack or whatever.

I opened it and it’s... a video game?

Introductions like these are commonplace among digital horror projects that fester and grow in niche places of the internet. It’s likely that unless you are searching for a project of moderate renown, you wouldn’t even know you were reading or watching one. They typically come camouflaged to appear as if they were the amateur game play footage of a grade school YouTuber, with videos titled like “Minecraft with my buddy part 1”. These projects trend toward science-supernatural and eventually show unexplainable events that thrust the most conspiracy-prone of us into our detective coats. The trick is, they aren’t games at all, at least not ones any of us can play. They start as something recognizable, but through creepy, tacked-on twists, they become an experience closer to a campfire story.

“I Found This Game” (IFTG) is a genre of Creepypasta digital horror that revolves around the unwitting discovery of a video game that is haunted, cursed, possessed, hiding a terrible secret, or has other equally disturbing qualities. To understand how these stories carved their niche in horror gaming history, we have to go back to just before the new millennium.

The Blair Witch Project (1999) is a found footage horror film that follows three students as they travel into the Black Hills to investigate the Blair Witch, a local legend in their town of Burkittsville, Maryland. The movie, released without advertising as was typical of indie horror flicks at the time, was passed around internet avenues as an underground release, purporting to be from three students who the movie lists in its credits as either missing or dead. The shock that this extensive multi-media project created forever changed the way horror could be experienced by inventing what is now known as “unfiction”, fictions that are presented as real, documented experiences.

Jumping ahead to about 2010, we see a boom in video game Creepypasta, as game modding became more accessible and easier to perform. The ability to modify a game and share footage on the internet of very realistic-looking alternate “haunted” versions frightened kids as stories and rumors spread from blogs, YouTube channels, and other sharing platforms. Tales from this time still stimulate the minds of internet historians as they give their interpretations of unfiction that bends and breaks nostalgia.

Notable releases during this time include Ben Drowned (based on The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask) by Alexander Hall, Red (Based on Godzilla: Monster of Monsters) by Cosbydaf, and Sonic.exe (based on the original Sonic the Hedgehog) by JC-the-Hyena. Larger projects like these are typically Alternate Reality Games (ARG) that ask their audience to explore clues over a wide range of media.

However, some of these take the form of simple internet rumors like the Pokémon Red and Blue “Lavender Town Syndrome,” where it was said that the Lavender Town song caused the suicide of 200 children in Japan during the game's 1996 release. While a closer inspection of any of these stories would easily reveal fantastical supernatural implications, a cursory glance could easily startle and rouse the imagination. When I was a kid and heard that Pokémon music was cursed, I totally believed it!

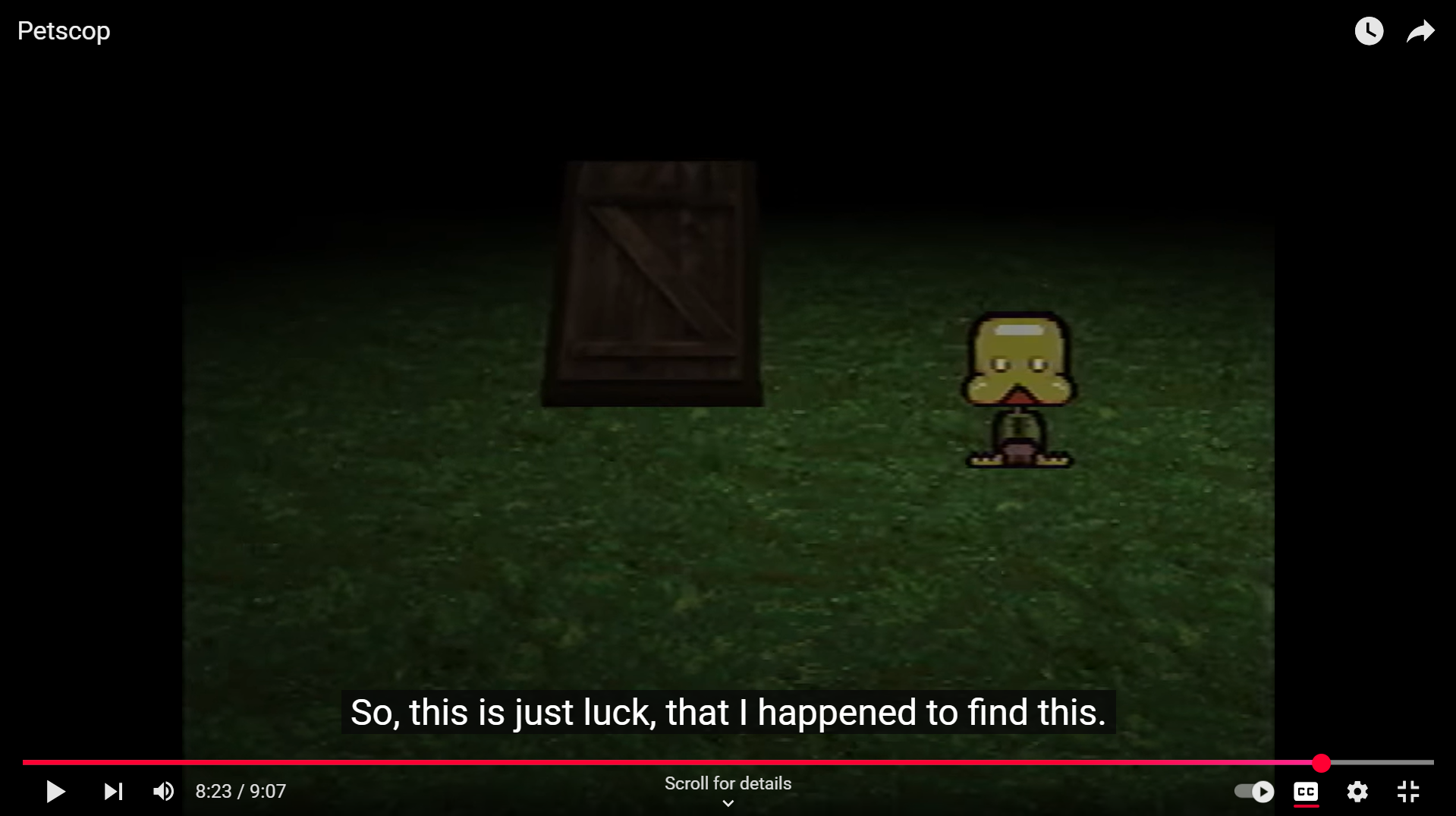

On March 12th, 2017, an uncredited YouTube channel called Petscop posted its first self-named video “Petscop”. The video comment reads “The game I found” and opens with our player, Paul, trying to prove to his friend that the PlayStation game that he found in his house exists. The game features several pets that you can collect by solving several environmental puzzles that are admittedly a bit unintuitive and counter to any normal puzzle game design. The game world is called the Gift Plane, which has a bright aesthetic, shades of pink, and a cartoon art style, giving the audience the impression that this is some long-lost children's game.

Eventually, Paul meanders down to a wide expanse filled with a grass-like texture and a night fog overlay. The mood immediately dampens as the light-hearted music disappears and the bright primary colors mute to a darker palette. Paul continues to explore the dark underbelly of the Gift Plane to find an entrance that oddly resembles a cellar door, implying that there is even more underneath. The first episode ends with Paul standing by the cellar door, not knowing what to do next.

If you continue to watch this series, you start to understand that the game is telling an oddly personal story to Paul that starts to taunt him as it continues. The crux of this story follows a warping of our understanding of the self-playing DEMO mode seen in many arcade games or some console games. The DEMO mode is meant to show potential players what the game looks like before they have to spend their hard-earned quarters to play. What is less known about DEMO mode is that this is typically not a video or a screen recording. DEMO mode loads into the actual game and the game is given the autonomy to play itself, the same way a player would. It’s an engaging series to watch that twists the role of game and player in incredible ways if you have the patience to stick with a slow-burning mystery.

I highlight Petscop first because of its stark contrast to, and inspired similarities with, our previous examples. Petscop exists in the same genre as the Blair Witch Project because of its commitment to a believable found footage experience in video format. It is also inspired by projects like Ben Drowned because it pulled on our nostalgia for early 2000s video games as a device for atmospheric horror.

But the most important difference, at least in the case of Ben Drowned, is that you can't play the exact horror version, but you can go play The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. You will never be able to play the original version of Petscop. There have been fan recreations, but the original creator might never release Petscop because it’s not a video game; it’s the set of a horror series. It is a video game built from the ground up to be played and filmed by exactly one person. Horror mods like Sonic.exe and Ben Drowned paved the way for modern unfiction creators to realize that game development doesn’t only have to create shareable interactive media. You can use game development engines to build your stage and bring to life your puppets as actors. Games today and those in the future are buying into this new ethos to produce even more engaging projects.

Published on November 7th, 2020, by Seirea, Diminish brings a new and even more believable spin to the IFTG genre. It is immediately confirmed that the game they are playing was made specifically for our player by his dying sister. This is (of course) not the entire truth as revealed by Seirea later, but regardless, it became the most believable unfiction story since The Blair Witch Project. Its grounded story and lack of traditional supernatural elements are the direct cause of this; however, the great portrayal of Will and the incredible detail poured into the game help its believability and popularity. The broad belief that Diminish was a real experience had gotten so out of hand that the creator eventually came forth to explain that he made the game to vent a personal experience and to help anyone going through something similar.

I’ve been nothing short of obsessed with these games that I can never play. The mystery and subtle horror achieved in these stories are incredible to behold. An evolution decades in the making, in the way that we scare audiences, proves that a game engine can be used in ways that we hadn’t even dreamed of before. The easier these tools become to use, the greater the creative projects we see, not just from the indie games space, but also the indie film space. If you like to watch gameplay and want to experience a hand-crafted horror narrative in the video game space, I urge you to find as many of these projects as possible. They are hidden and waiting for their audiences to stumble upon them, mistaking their spooky premises for reality.