Hidden Gems of Game Design Vol 43

Unearthing the Gemcraft series, Beyond Sunset, and Zoo Tycoon

Plenty of amazing games go unnoticed and are not played widely, for various reasons. Maybe it’s a diamond in the rough, or the marketing wasn’t there, or it could be a game ahead of its time. For this monthly series, I’ve asked my fellow writers at SUPERJUMP to pick a game they think is deserving of a chance in the spotlight. Please share your favorite hidden gems in the comments.

Josh Bycer

Gemcraft Series

For this month’s pick, I want to go with an indie series that I’ve hoped could be an inspiration for other developers. Gemcraft started as one of the many online games featured on the site/portal Armor Games, and two of the five in the series are currently available on Steam.

Gemcraft is, to my knowledge, the first tower defense roguelite. The story follows wizards who are doing battle against monsters using magic towers with gems to keep them at bay.

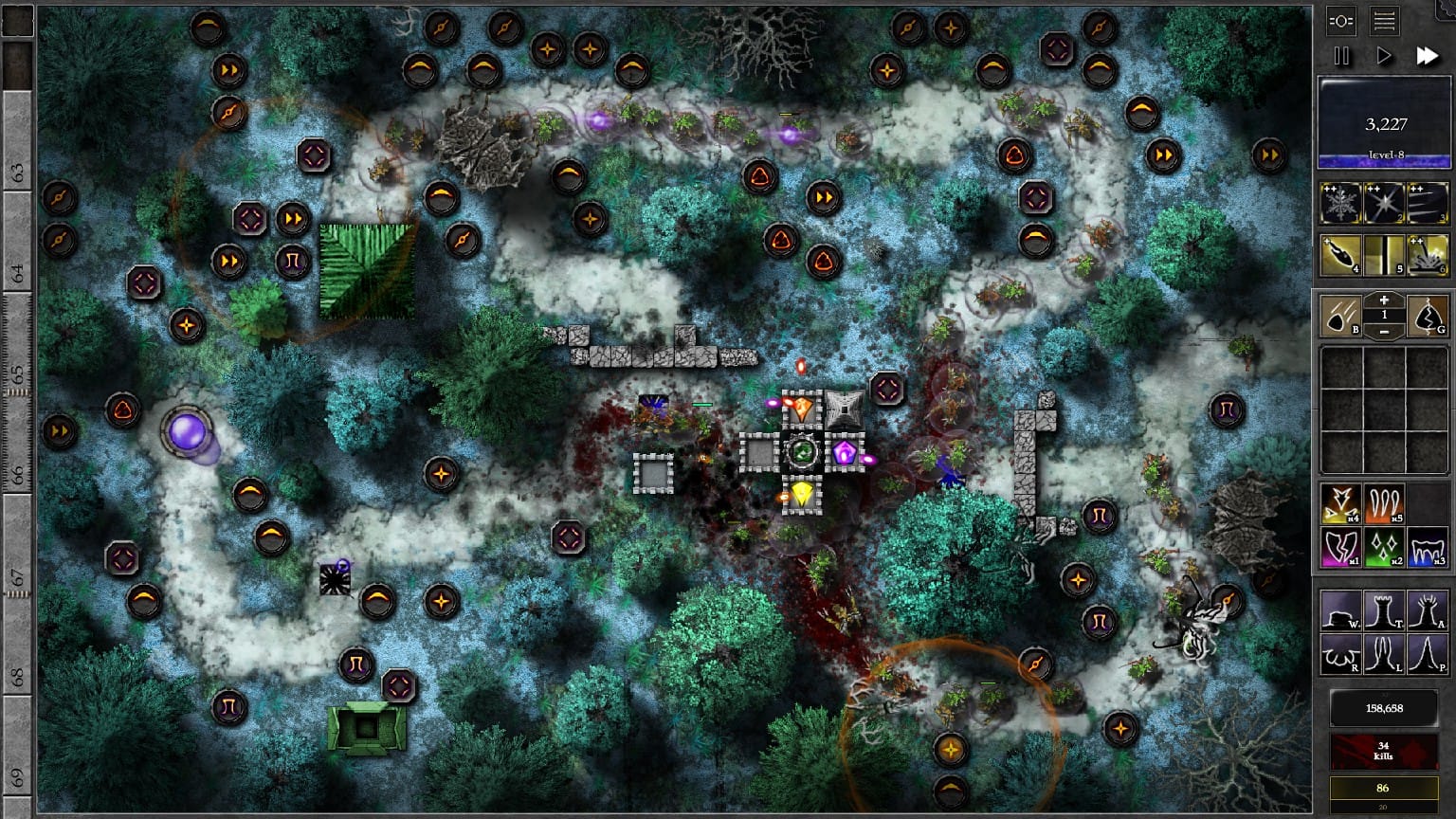

Three main systems make up each game, starting with the tower defense. Your mission is to defeat waves of varying enemy types using the gems and buildings provided. You have almost-free rein to build wherever you want on the map, but you must protect your wizard orb to win. Gems come in different colors that affect their properties, with different gem colors appearing in each game.

The gems themselves are your actual weapons, and can be put in different structures to change their role and be upgraded. Towers are the default structure, while traps do less damage but enhance the special properties of a gem. On many maps, wizard stashes can be opened to provide you with a reward that goes with the other systems.

Winning maps and getting a new high score will reward you with experience that can level up your wizard. This provides skill points that can be applied to unlockable skills, grant passive bonuses, or unlock powerful spells that can be used during a map. Any unused skill points will provide you with bonus mana (which purchases and upgrades gems).

Each game has a “talisman” that acts as the meta progress. Randomly, while playing maps, a talisman piece can drop, and the higher the number, the rarer the talisman. These provide bonuses that affect damage, how much mana you get, and other buffs. But to get the best parts, you have to take Gemforge into overdrive.

Each map can be played three ways – the story mode, trial (AKA puzzle mode), and endurance. Endurance mode is the best way to get high scores and talisman pieces. One of the unlocks you can get is battle traits that can be applied to a map, cranking up the difficulty while increasing drops and experience. The more traits you have, the greater the rarity of the talisman pieces you can obtain. This is when playing Gemcraft almost turns into the game-breaking style of Disgaea.

Filling out your talisman is going to take a long time, as you need shadowcores to unlock more spaces, and the cost gets progressively more expensive as you get further into it. There comes a breakaway point in every Gemcraft title, where the player goes from barely being able to survive endurance mode to cranking up the difficulty and getting a boatload of cores and powerful talisman pieces.

Learning and mastering any Gemcraft game is going to take some time, and you can easily get dozens of hours in each if you want to do it all. However, when it comes to onboarding and helping the player learn how to improve, the game falls a bit short.

Maps are easy until they’re not. Each wave increases the attributes of the enemies, and the killer of your run at the start will come from a horrible 5-letter word – armor. For each point of armor an enemy has, it will block incoming damage. Pylons ignore armor, and the armor shred gem outright counters it. However, on maps when you don’t have access to armor shred, or the armor shred is too weak, you can go from one-shotting every enemy, to the lightest enemy shrugging off all your attacks.

This requires you to build nothing but towers aimed at your pylons to be able to smash through them, up until the point when critical damage becomes the predominant damage dealer. This gets to a fundamental crack in the design and how it scales up. Your ability to deal with stronger and stronger waves is dependent on the skill tomes you find, which affect your viable options. There is a distinct difference in how you approach these maps as a beginner, moderate, and advanced player. While the game offers multiple ways of playing, this comes at the cost that there is often one preferred strategy per map.

Traps are great against slow or medium-speed enemies, but don’t fire fast enough without upgrades to deal with swarmlings. Putting points into your trap skill means that you’ll have fewer points for the skills that give you a base damage increase. I absolutely did not like lanterns, which hit multiple enemies at once, but deal far less damage. If you plan to play multiple games in the series, however, mastering one of the games means you should be able to handle anything that gets thrown at you in the others.

At some point, no matter how skilled you are at maze design or building the perfect choke points, you either have enough DPS to get through the enemy defenses and numbers, or you don’t. The difficulty also gets tuned up when RNG comes into play; while the waves and map are fixed, apparition attacks are not. After you reach a certain map point, the game will start spawning different kinds of ghost enemies throughout the map. The spawn timings are fixed, but what spawns is not. You could get something easy, like a passive specter that flies around, or you could get a demon that summons more enemies, attacks your orb directly, and is just a horrible nuisance.

What I find fascinating about Gemcraft today and why I wanted to talk about it, is that the tower defense genre faced an evolution crisis in the mid 2010’s to remain relevant as the market changed. It could have gone in three directions – following the roguelite progression set by Gemcraft, the character as a tower style of Defender’s Quest and popular mobile games like Arknights, or turning the tower defense itself into a roguelike.

Developers have responded by making their games more like the latter two, and leaving Gemcraft’s design all but gone in today’s market. The series remains an interesting branch of tower defense design, and if you ever wanted to see just how powerful you can make a tower, and have a lot of hours to play, then you need to check it out.

It remains up in the air as to whether we will get another game and a conclusion to the story. The developer sadly developed a rare liver disease, and updates have been sporadic. I’m hoping that they are doing well and that more people hear about this series.

Ben Rowan

Beyond Sunset (2025)

I grew up on Doom, Quake, and Half-Life, so I’ve been chasing that boomer shooter buzz since way before we called them boomer shooters. I’ve sunk plenty of hours into modern spins like Ion Fury, Dusk, Turbo Overkill, and Prodeus, always hunting for that latest hit of speed, violence, and retro attitude. Beyond Sunset is the most recent one to grab me, and its mix of old-school DNA with modern touches and a slick cyberpunk style certainly helps it stand out.

Developed by an elusive one-game studio, Metacorp/Vaporware, Beyond Sunset is a cyberpunk RPG shooter built on the modern GZDoom engine. It runs incredibly smoothly, even on my ageing MacBook Pro (M1 Pro), and that fluidity matters in a game like this. Movement is fast and responsive, which is ideal for a game where, like the modern Doom reboots, pushing forward into combat encounters is usually the right answer.

In fact, combat is where the game really shines. There’s a wide variety of enemies, and lately I’ve been ploughing through hordes of robots of varying difficulty. Some are clearly designed to be mowed down, and they drop health and ammo generously, which keeps you playing aggressively and staying in motion. You’re not hiding behind cover or aiming down sights here either, you're constantly moving, dashing, and clearing rooms at speed. When tougher enemies show up, like shielded guards, flying drones, or flame-wielding mechs, the level design gives you enough space to reposition, heal up, and swap to heavier firepower.

The weapons feel great across the board, too. The pistol has a strong alt-fire that’s perfect for cracking shields. The assault rifle is reliable and satisfying, and the shotgun is exactly what you want when a giant robot stomps into the room. And yes, there’s a samurai katana that lets you carve through enemies and even reflect bullets, Jedi-style. It’s the first weapon you get in-game, and definitely the most fun.

Beyond Sunset has more going on than most boomer shooters, adding RPG elements that deepen the experience. You can boost your character’s stats, buy upgrades in shops, experiment with power-ups, and talk to NPCs for side quests. It’s not quite classic Deus Ex, but it has that same sense of a deeper world that rewards exploration. The neon palette and synthwave score lighten the tone compared to Ion Storm’s dead-serious classic, but the intent is similar. This is a shooter that wants you to poke around and engage, not just sprint to the exit.

Like vintage Deus Ex, level design is ambitious, too; these aren’t straight corridors. They’re sprawling, maze-like spaces with multiple floors and multiple objectives, though sometimes they’re a bit too sprawling, and it’s easy to lose your bearings. But with a little patience, plus help from in-game computer terminals that let you access CCTV feeds, you can usually piece together where to head next.

Beyond Sunset isn’t reinventing the genre, and it doesn’t need to. It’s a solid, stylish boomer shooter with personality that understands why these games worked so well in the first place. Considering how well this GZDoom-based game runs on my Mac, it gives me hope we might finally see the brilliant-looking Selaco land on macOS once it leaves Early Access. For now, I’m genuinely having a great time with Beyond Sunset. It’s a certified hidden gem for anyone who wants that old-school shooter energy with a bit of classic RPG flavour.

Anonymous

Zoo Tycoon (2001)

The passing of an ill lion cub was a difficult subject for Lincoln Park Zoo’s communications manager when I spoke to her in Chicago. It stirred a memory I had almost forgotten: my encounter with death in Zoo Tycoon (2001).

Seeing green smiley faces pop up over my pride of lions meant I was doing something right as a kid. I picked the right trees, the right terrain, everything they could ever need. Ever the utilitarian, I let my lions keep their default names: Lion 1, Lion 2, and so on. After a couple of hours, Lion 1 was missing.

The next few minutes of frantic searching confirmed my worst fear: he was dead.

I loved spending time with animals at zoos or with plastic toys at home. In-game, I’d spend hours crafting environments and appeasing guests, often at the cost of profit. The animals’ info panels were a goldmine of real-world facts that made it simple to build habitats and meet their needs.

Once your animals showed their satisfaction with the aforementioned smiley faces, it was the guests’ turn. Attractions and shops kept visitors busy when they weren’t waiting in restroom queues. By getting funds from tickets, concession stands, and donations, you’d earn enough to build your next enclosure.

As a game that promotes animal preservation, it’s ironic that there’s no simple way to play the original Zoo Tycoon. Despite working on a sequel and teaming up with Nintendo for World of Zoo on the Wii in 2009, the studio shuttered in 2011. Zoo Tycoon remains a great tool to explore nature’s ecosystems by raising a zoo of miniature animals.

A Final Message for 2025

This is Josh again. Thank you so much for reading these monthly pieces and enjoying the series throughout 2025. It has been a pleasure giving smaller games a chance to be seen, and I hope that a few of you were inspired to check them out.